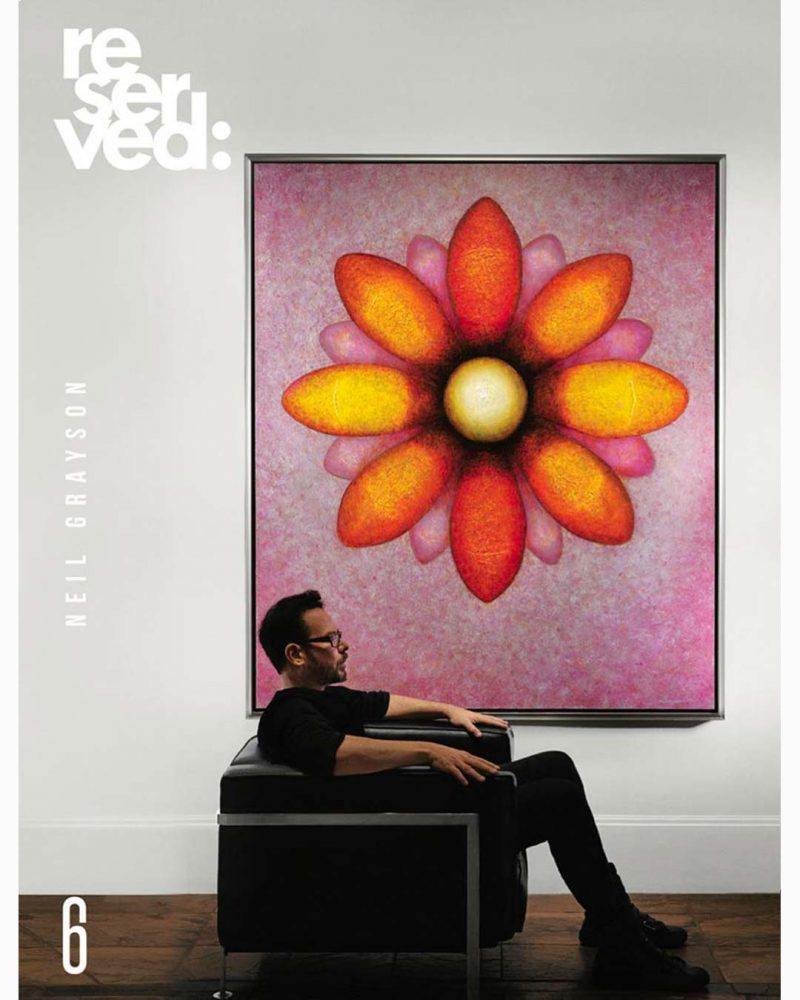

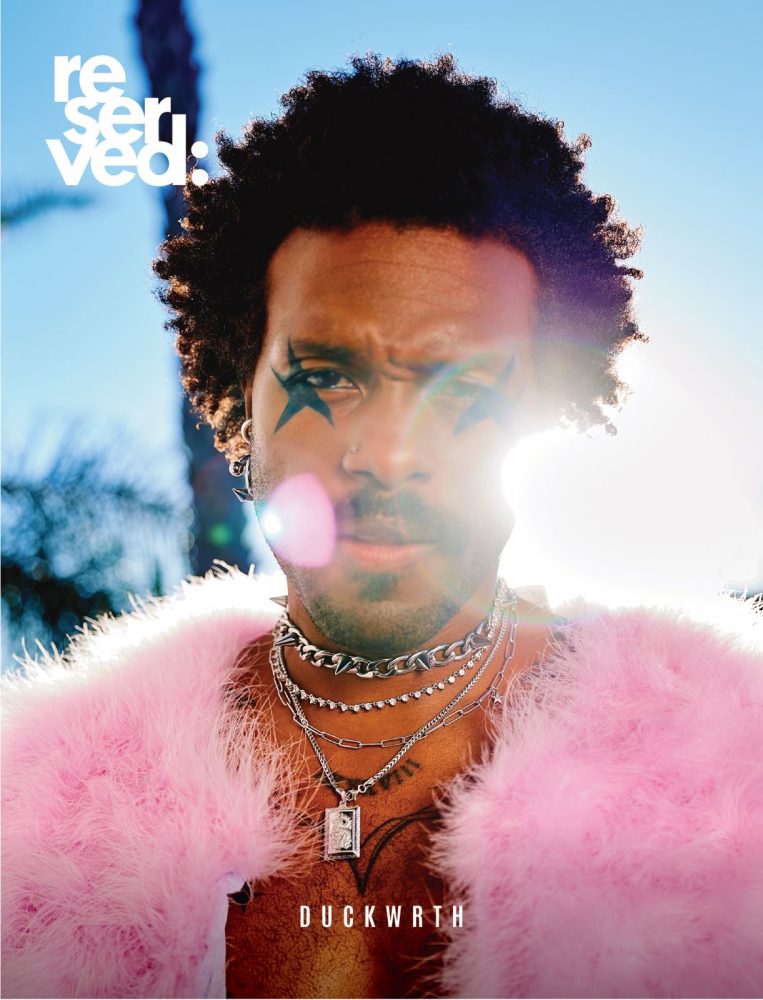

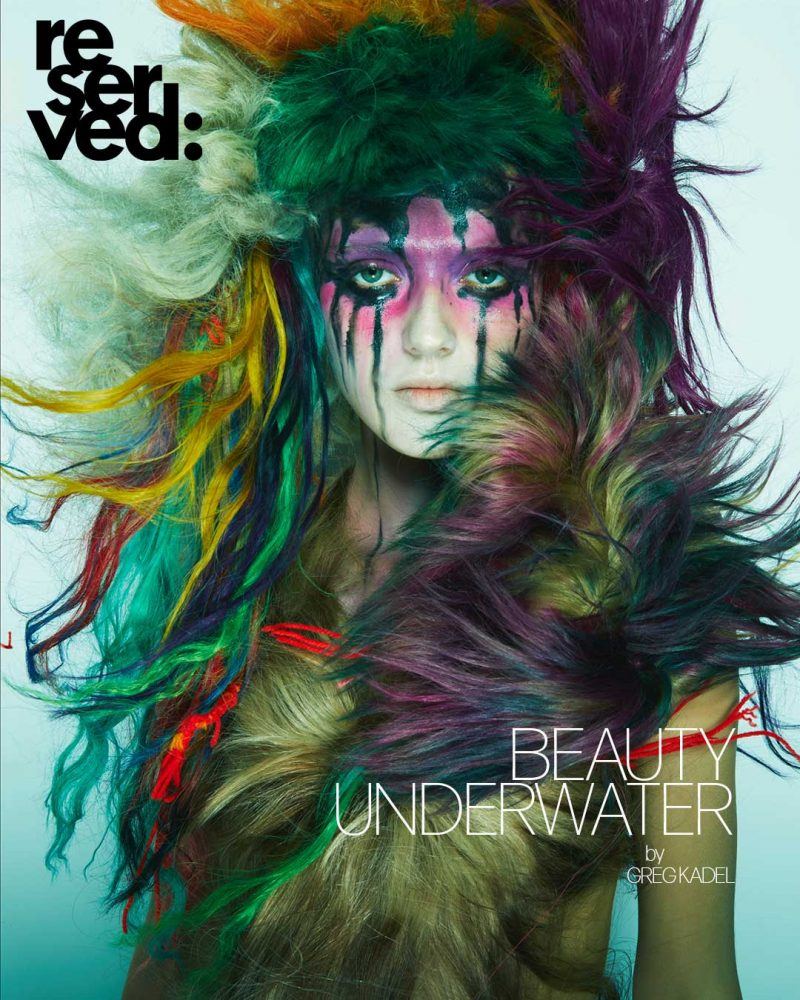

PANDEMIC FLOWERS

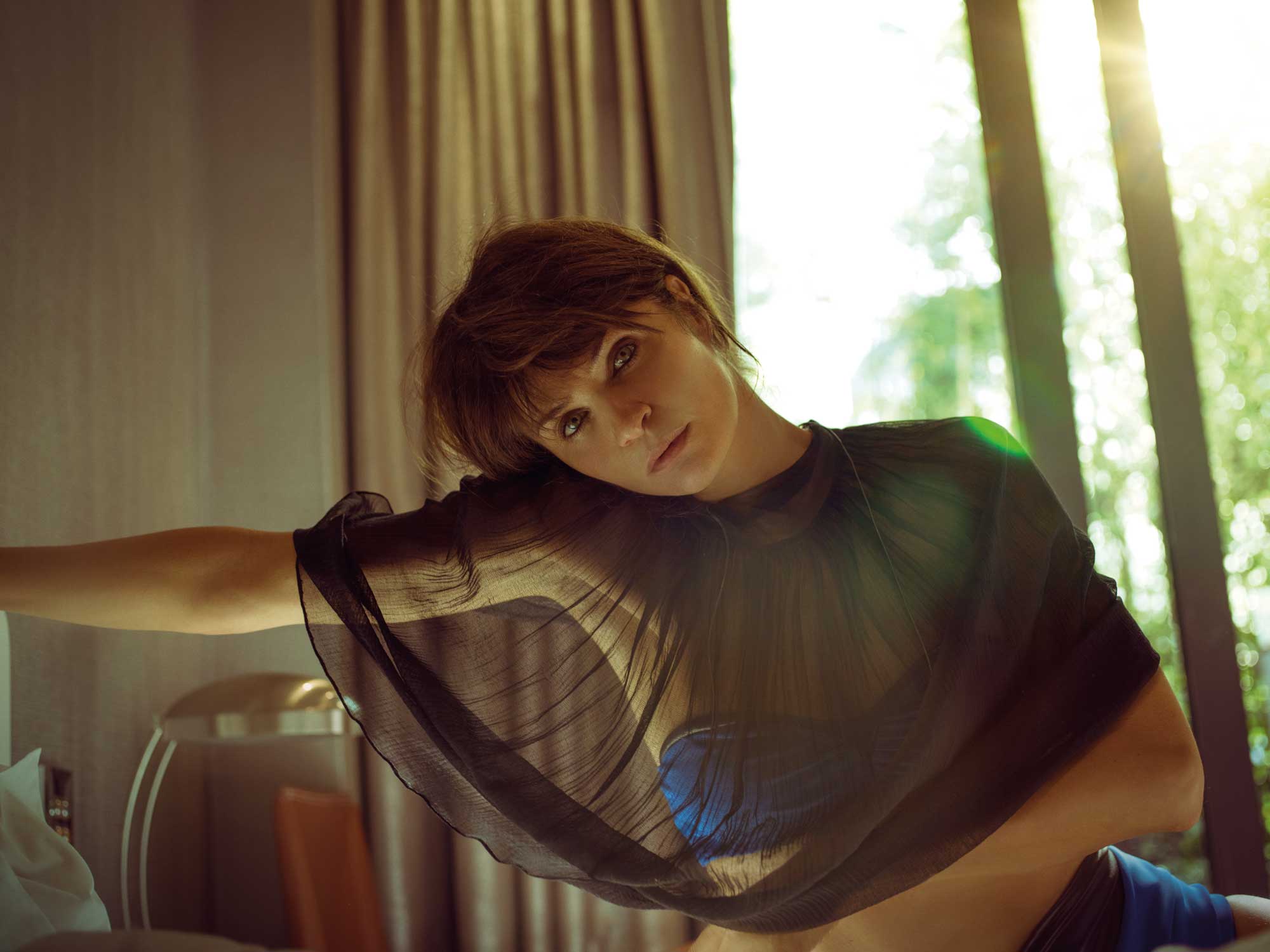

ARTIST NEIL GRAYSON

interview by Victoria N. Alexander

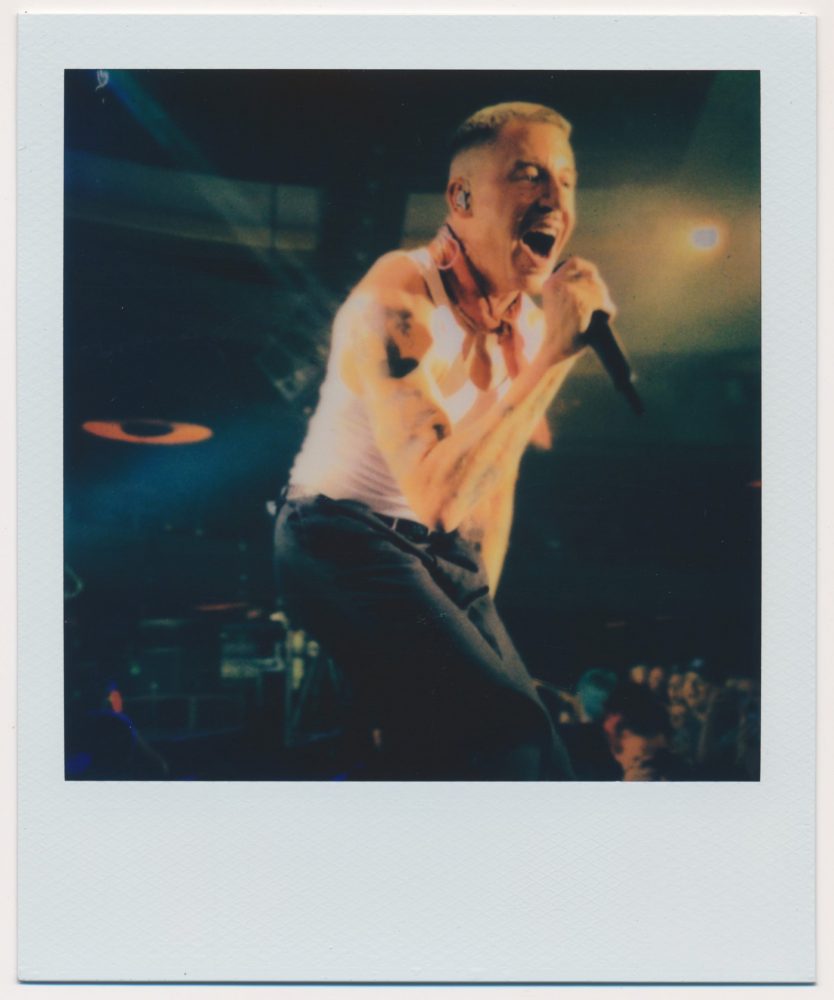

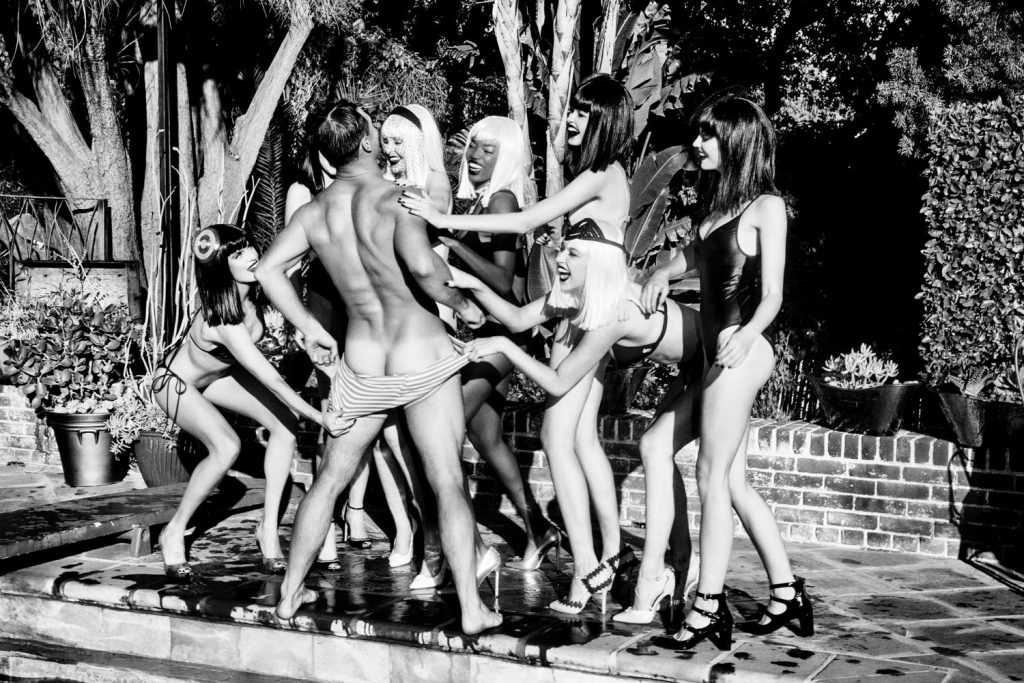

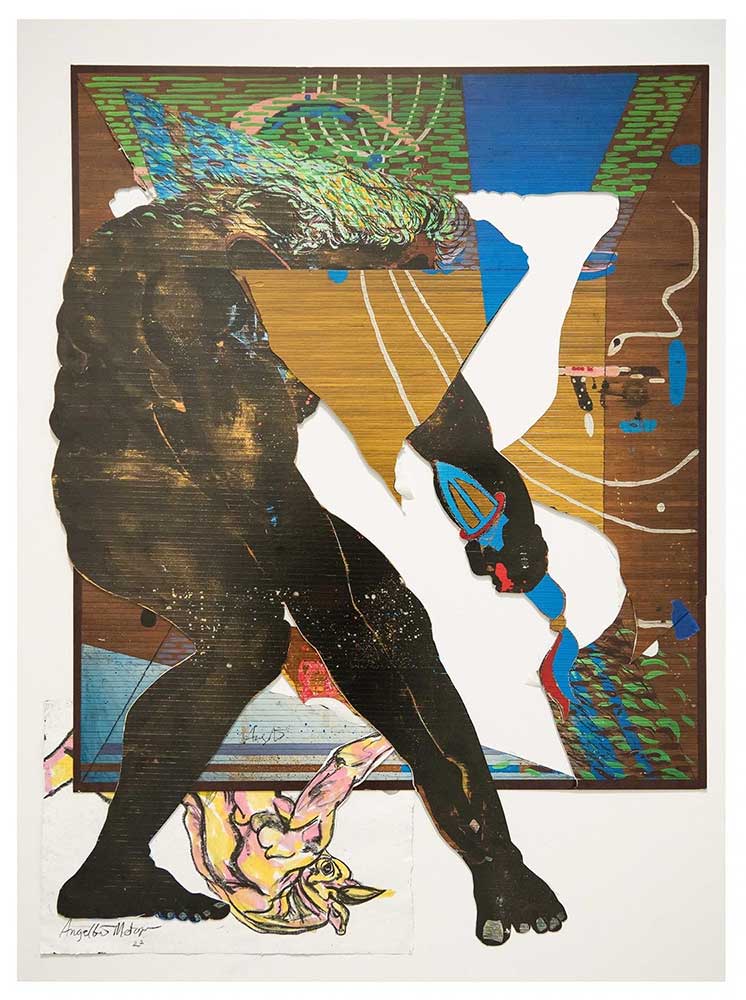

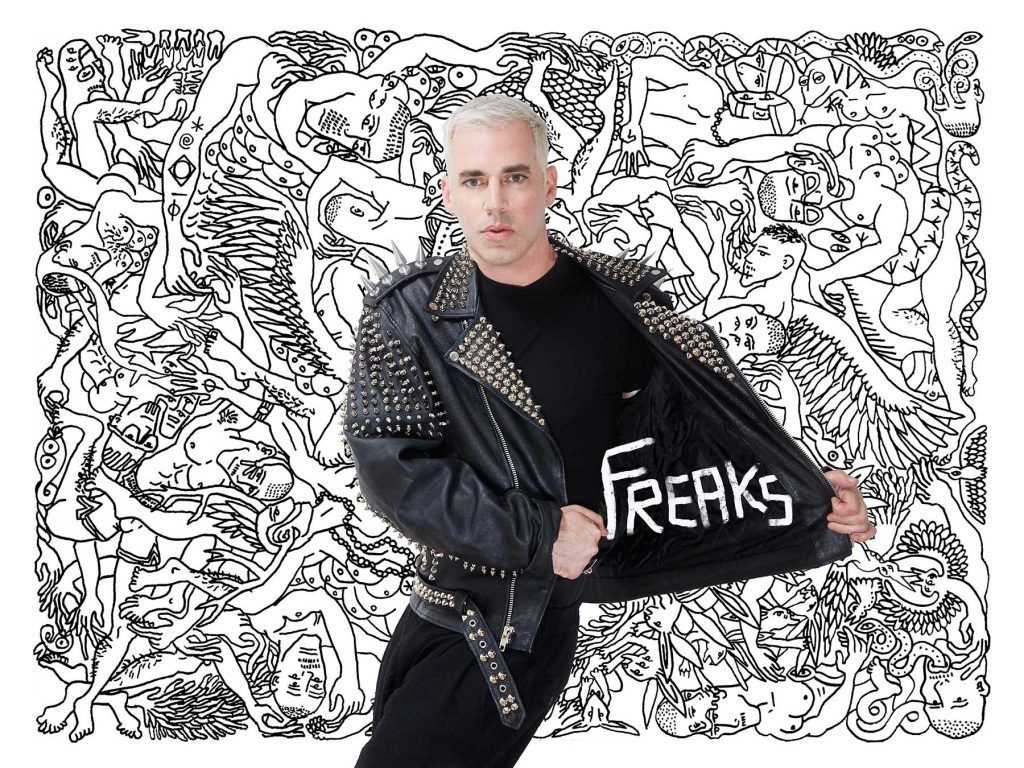

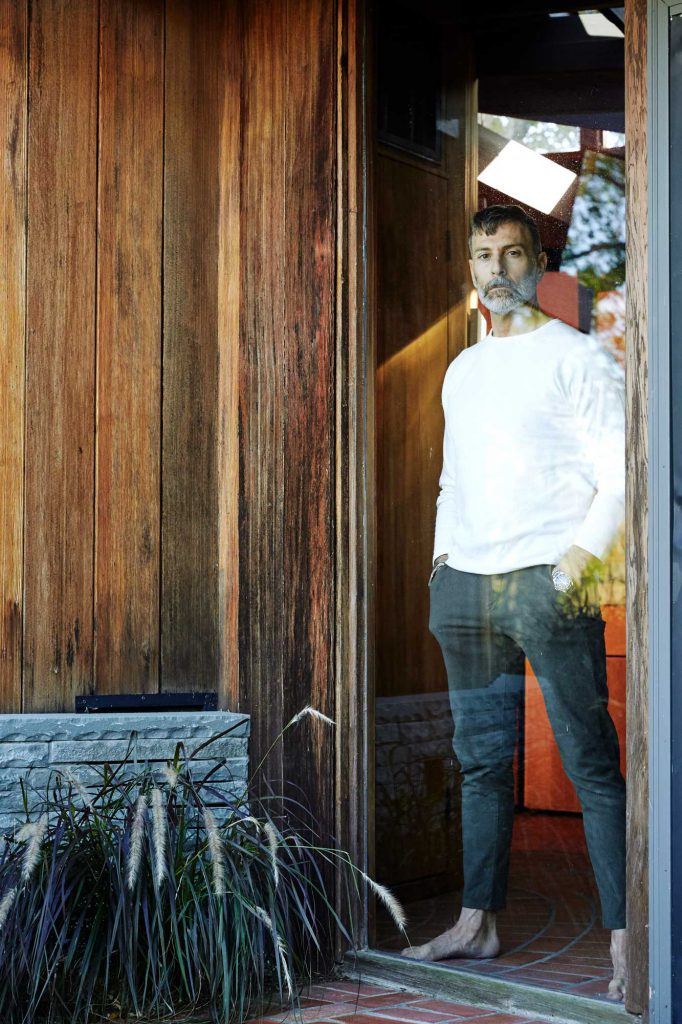

Neil Grayson prepares his brushes by smashing the bristles straight into the wall then removing the damaged ones with duct tape. This ritual is to ensure the remaining bristles are strong enough to endure his unconventional brushwork. He prefers extra-long brushes; they are more difficult to control. He rolls each one lengthwise in the oil paint, so they pick up pigment randomly, then strikes the canvas with them. The result is an unpredictable pattern that Grayson then sculpts into content.

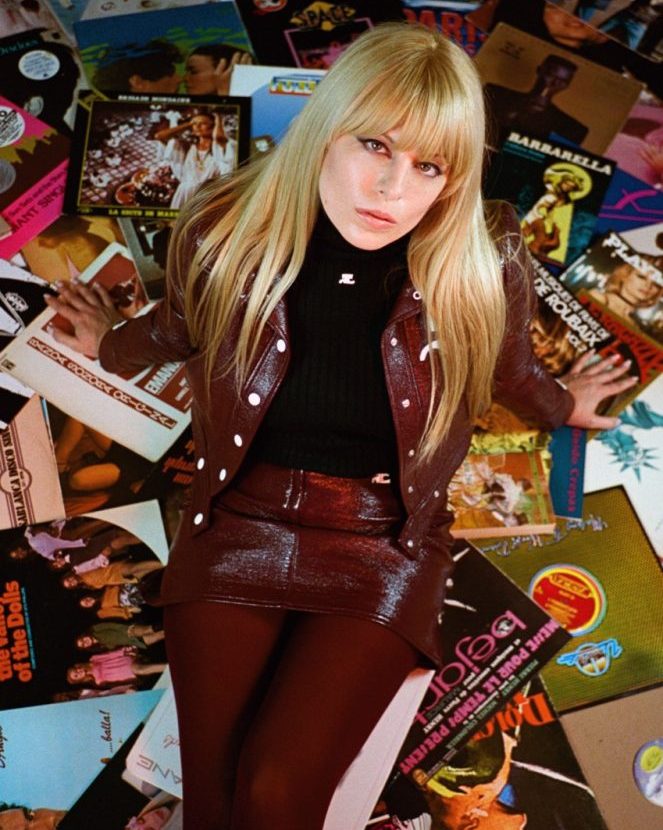

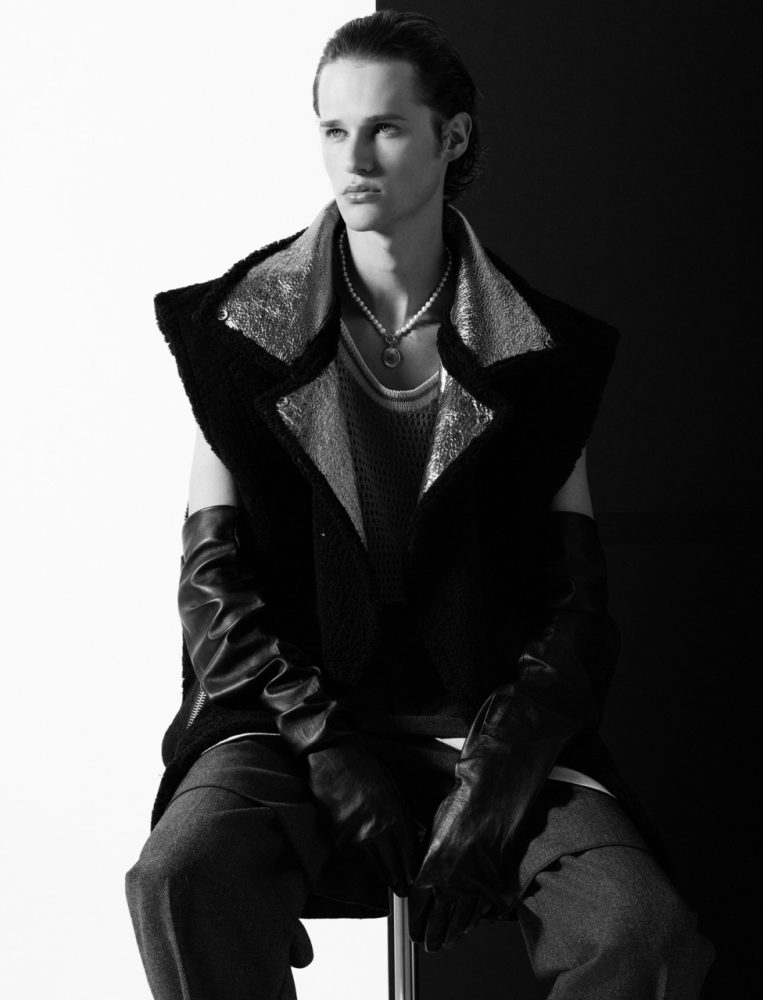

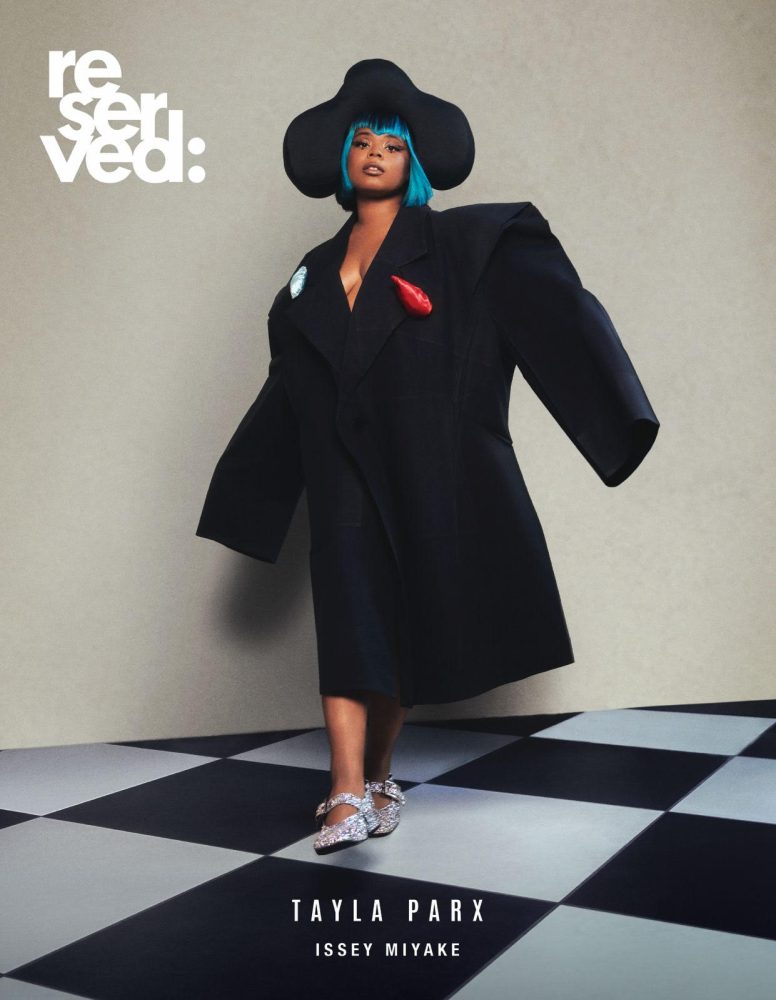

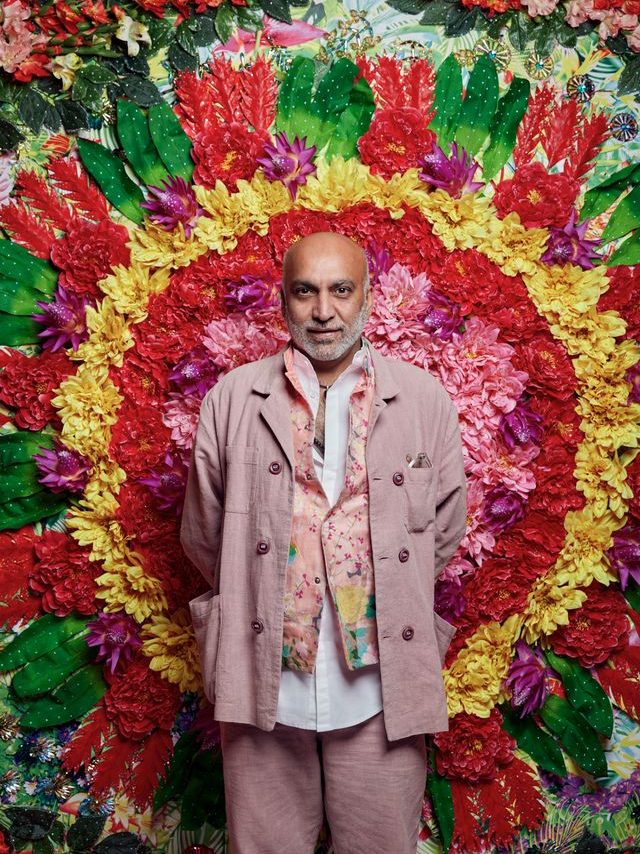

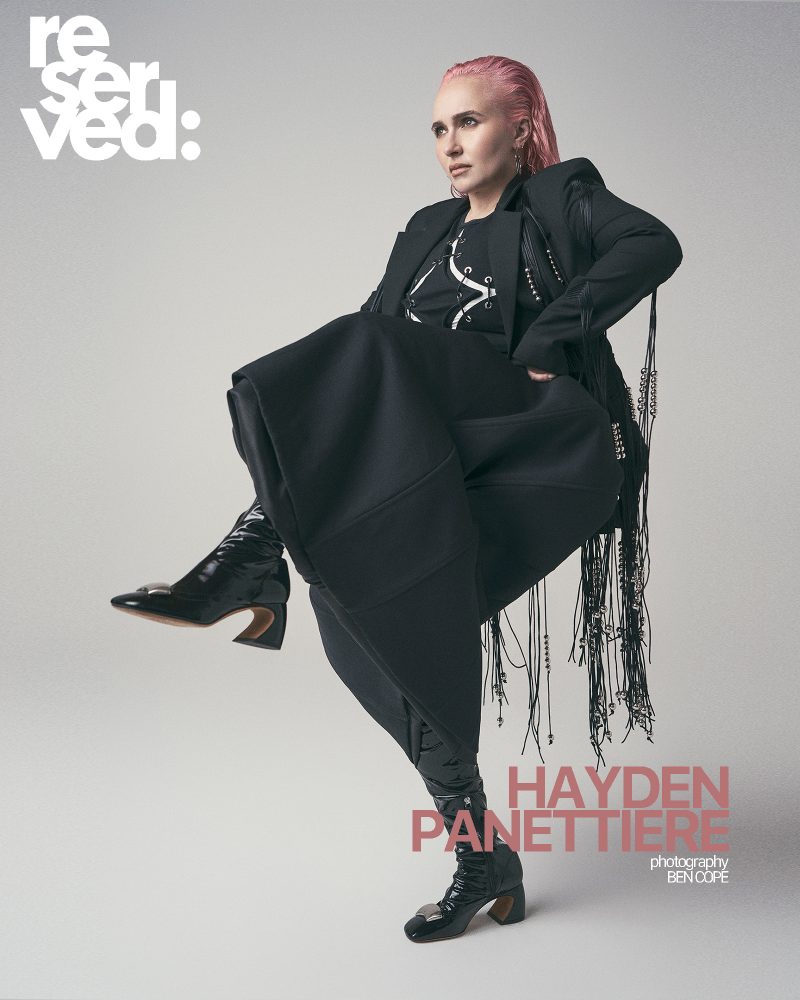

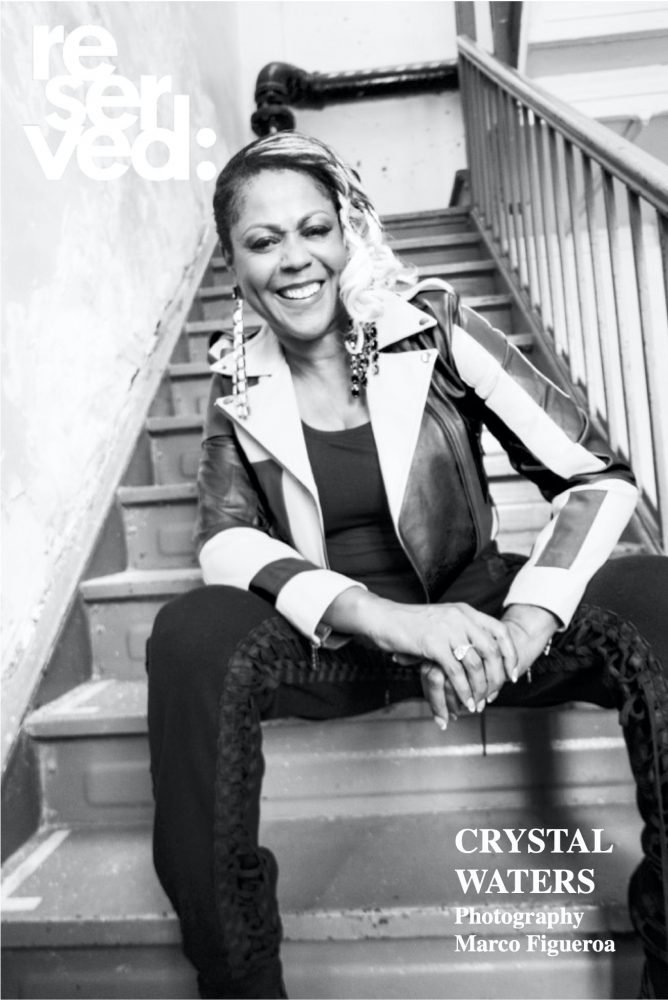

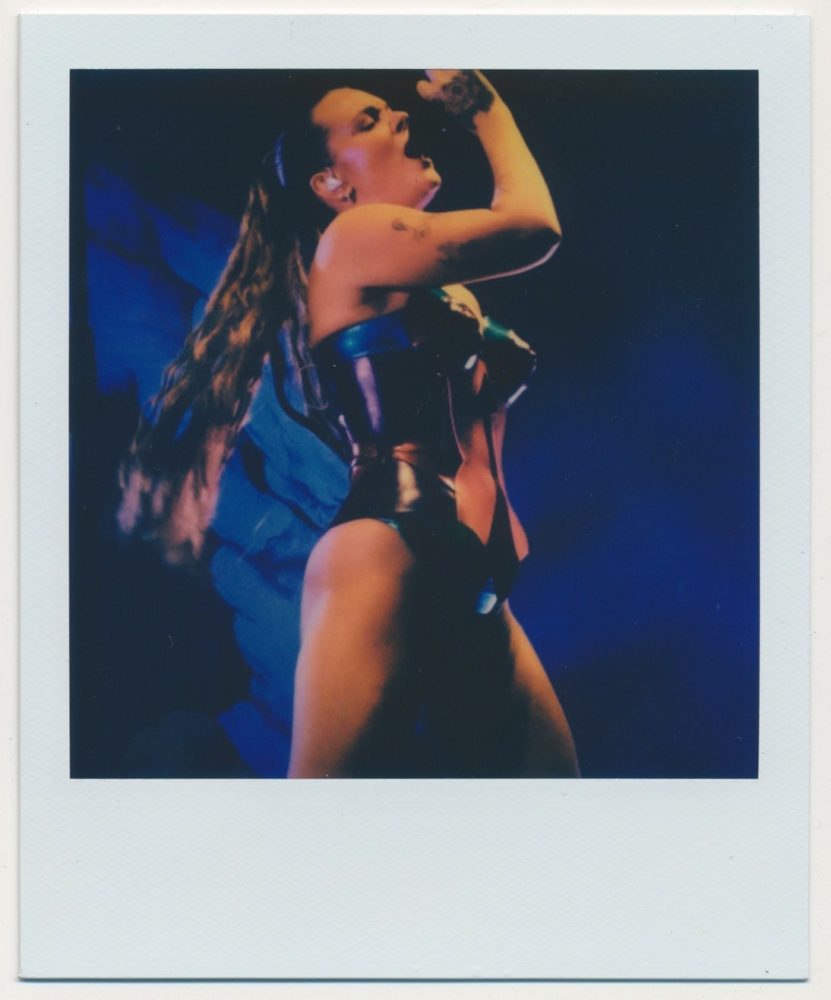

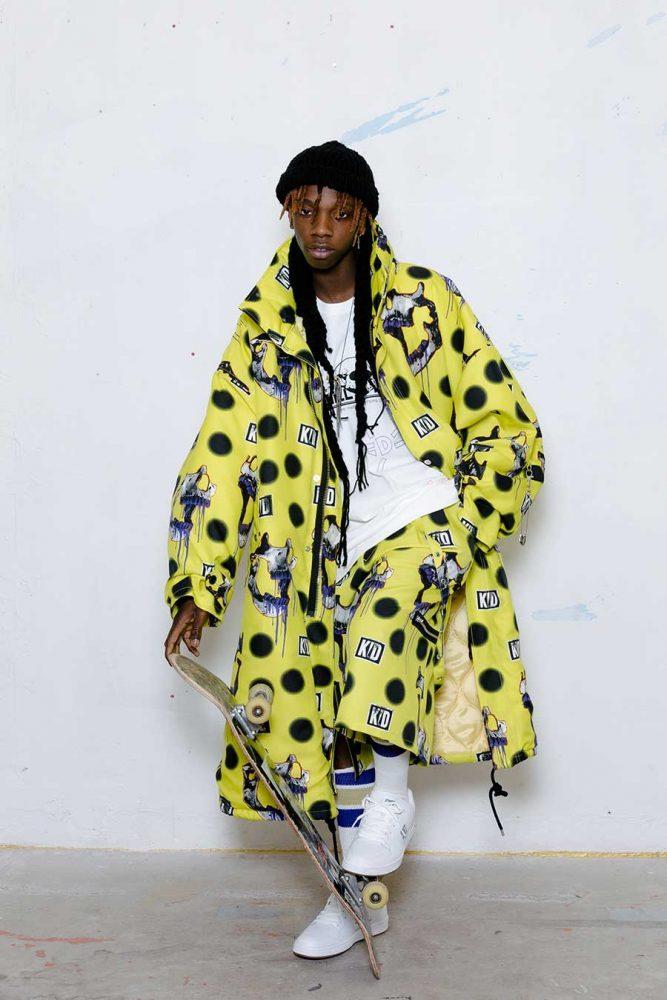

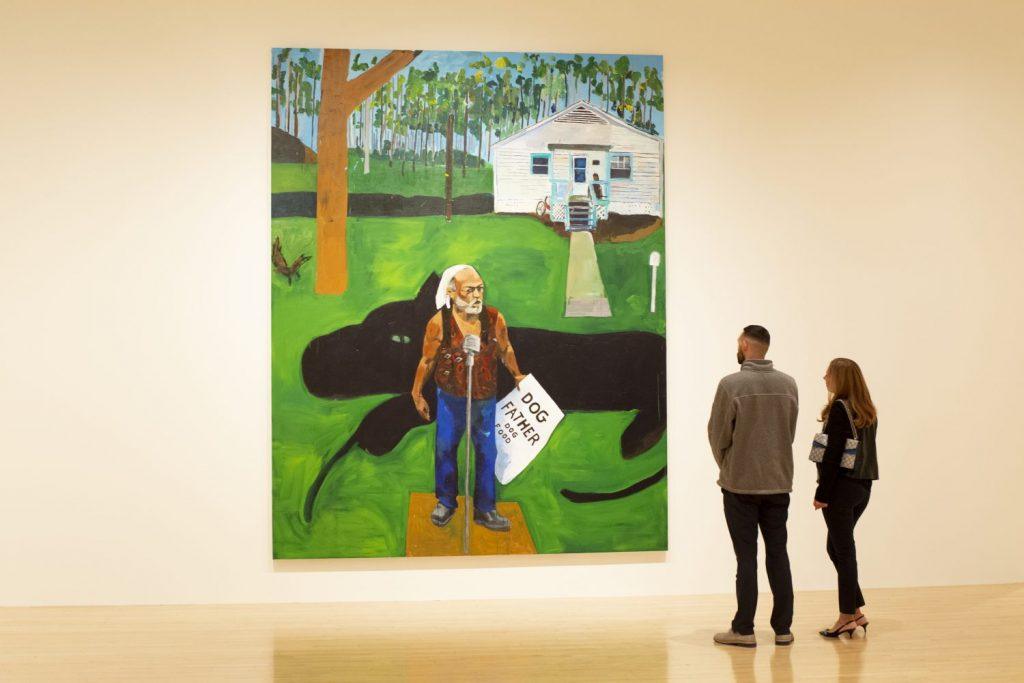

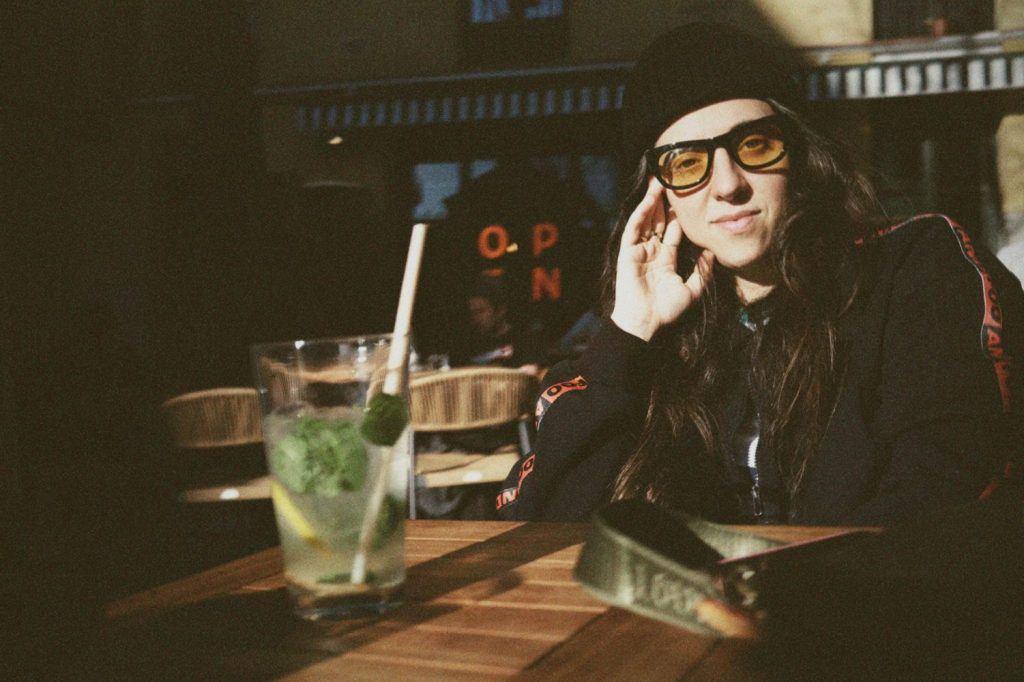

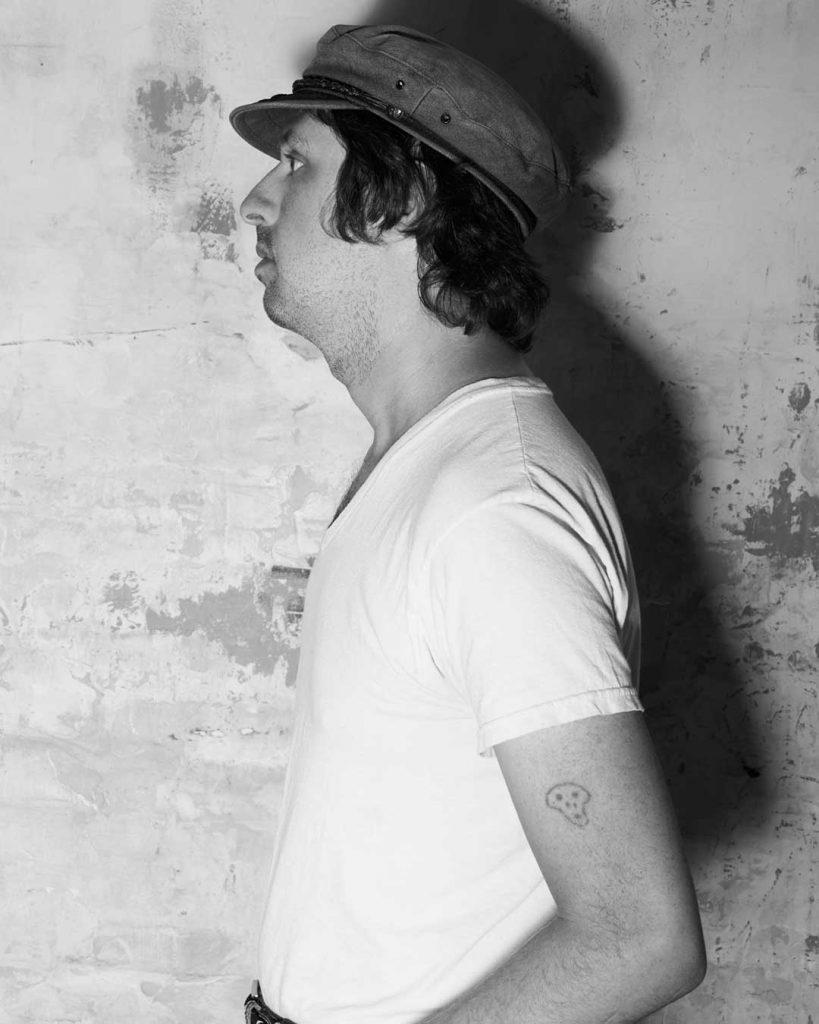

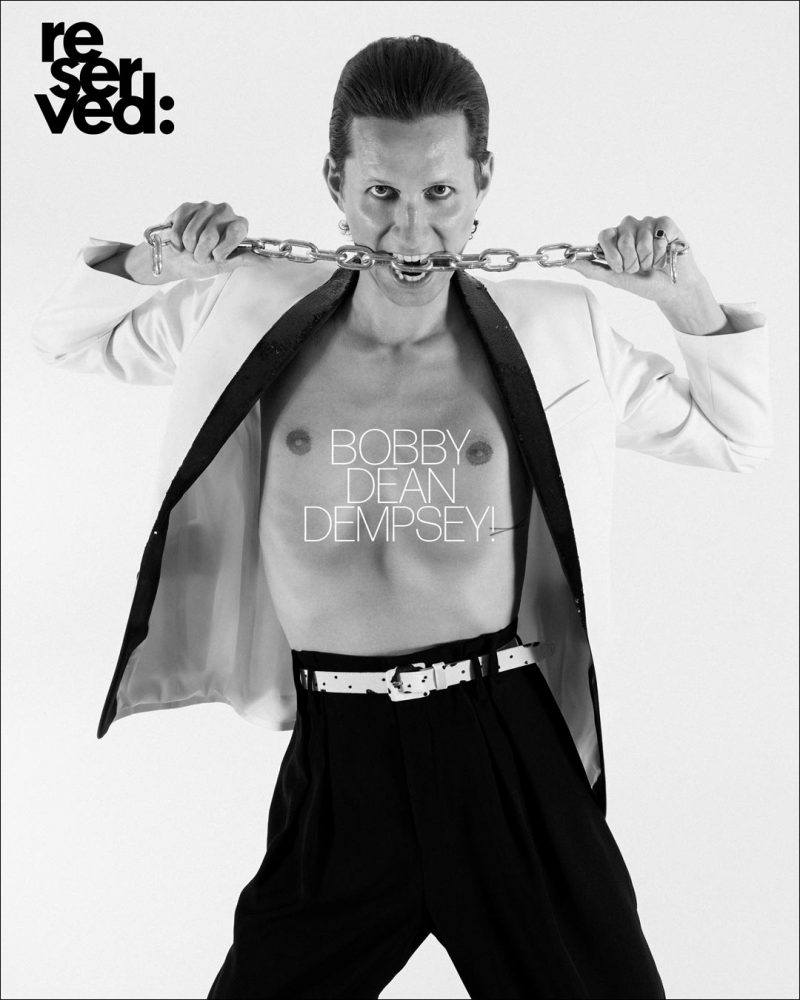

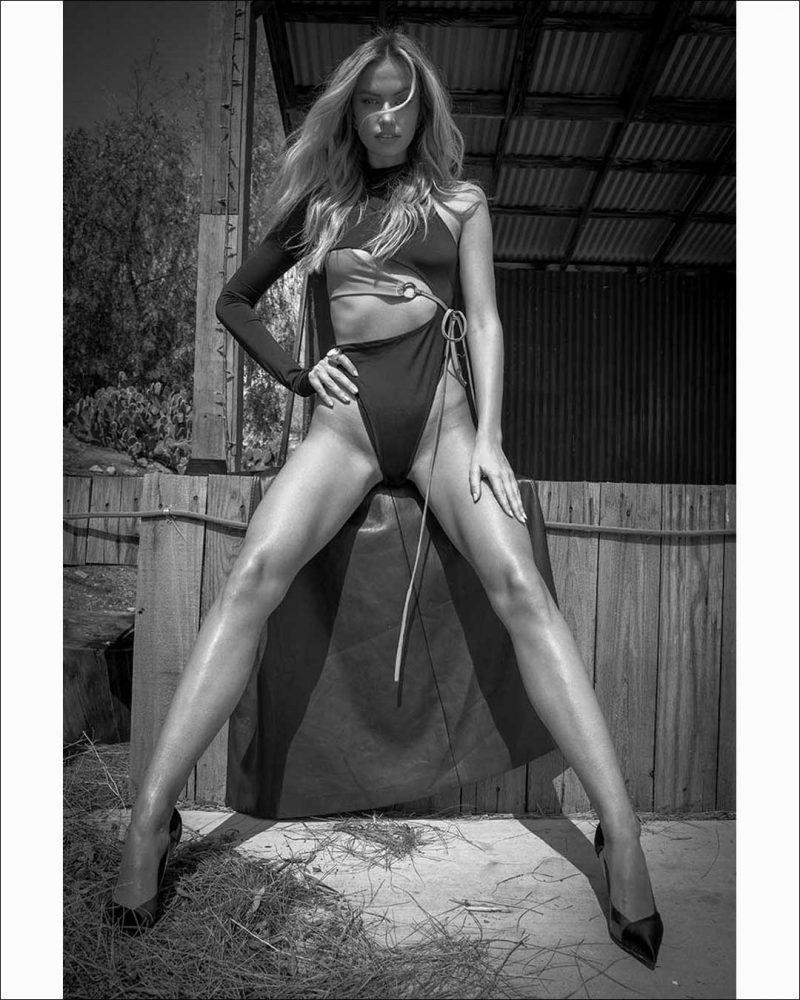

Neil Grayson in his studio with a portrait of the artist’s father, Herbert L. Grayson. Photographed in New York City by Maddox Grayson.

Creating art, in the midst of one of the most unsettling times in recent history, seemed to Grayson the only thing to do. He is adept at finding structure in chaos. Working during the lockdown in his New York City studio, Grayson says he felt like he was in the “eye of an information storm.”

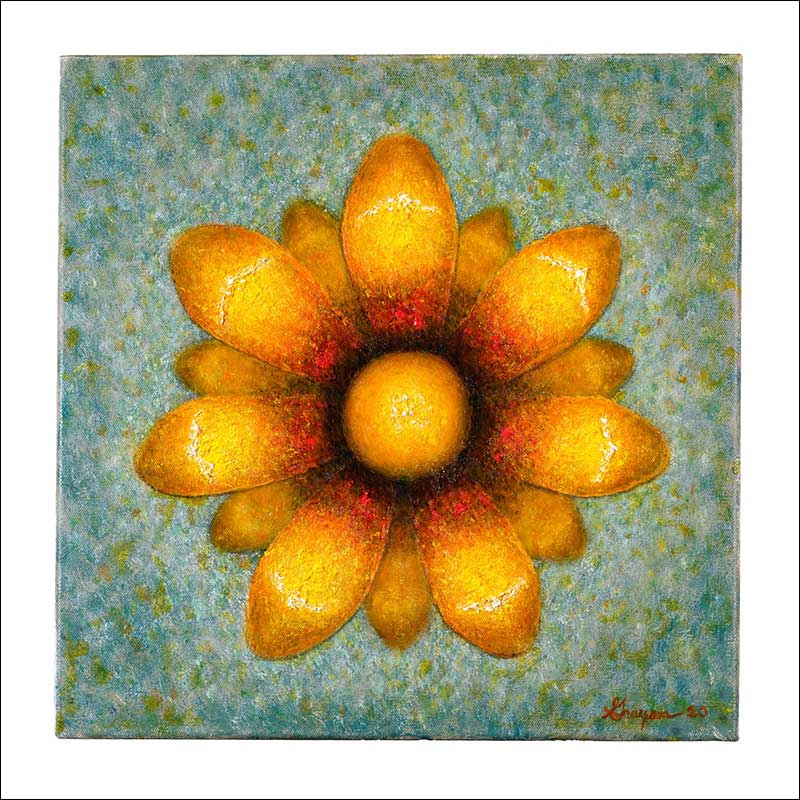

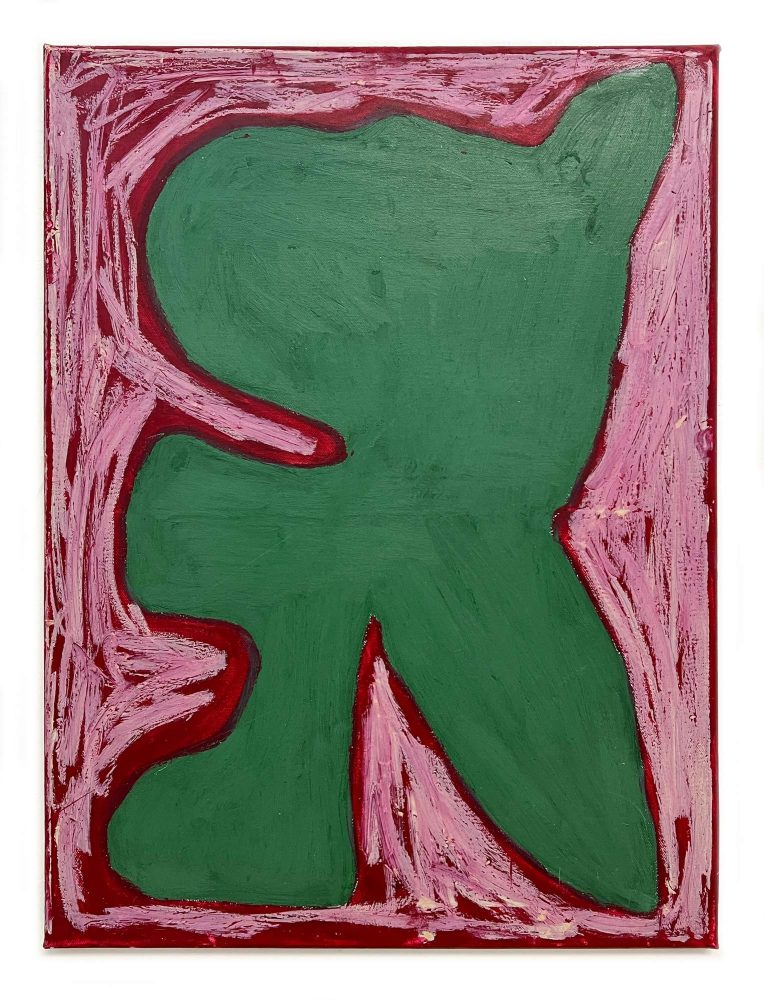

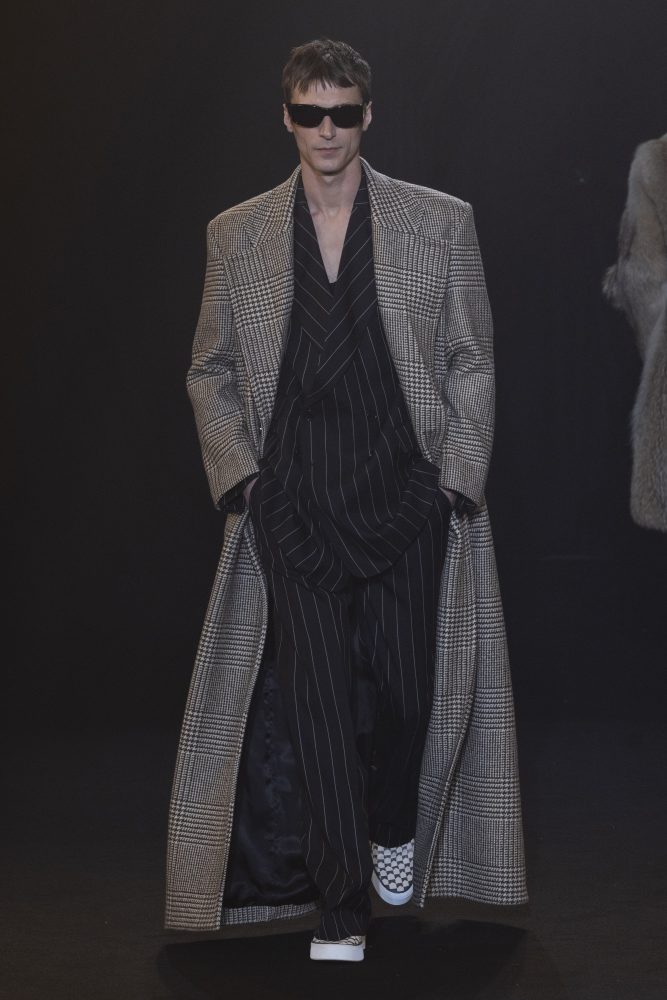

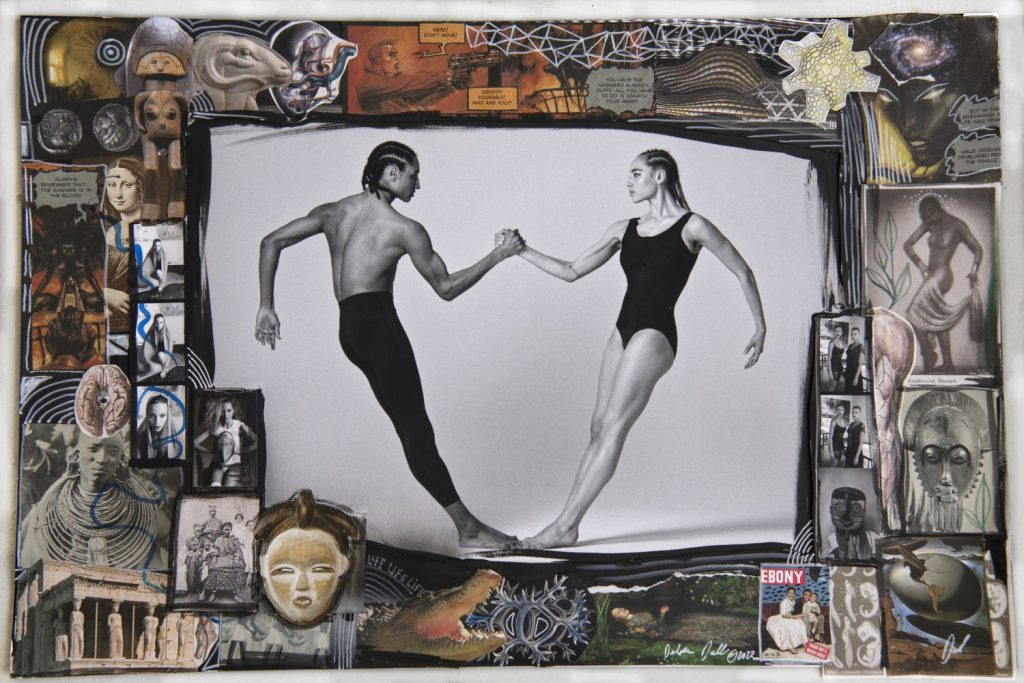

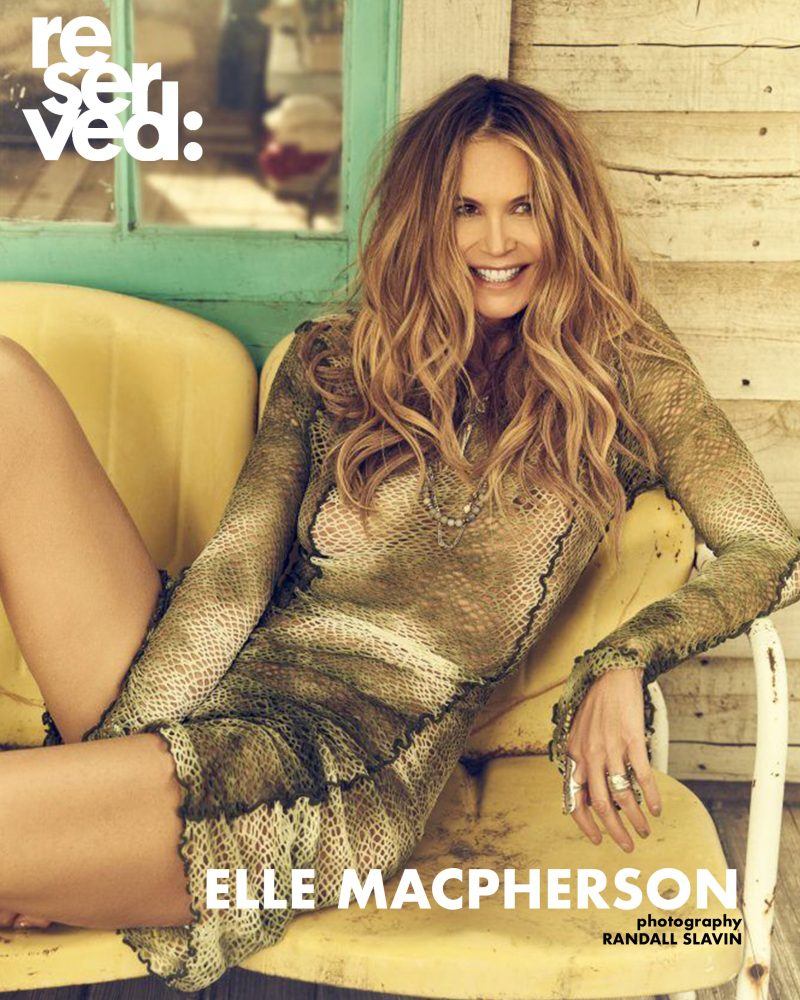

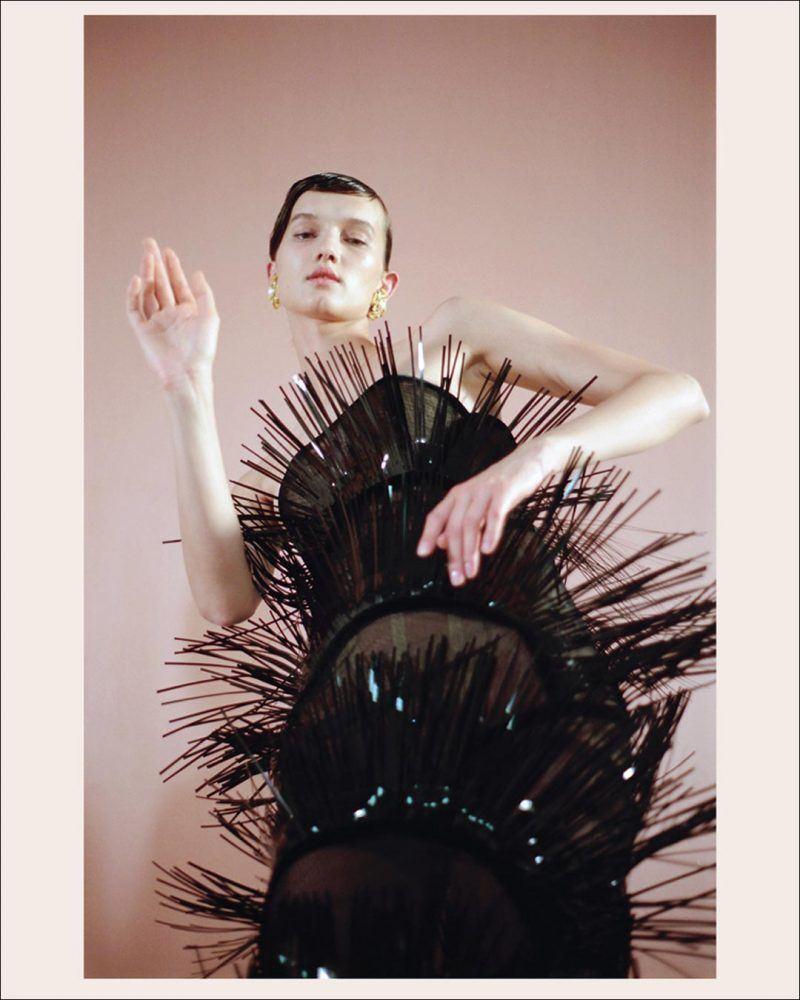

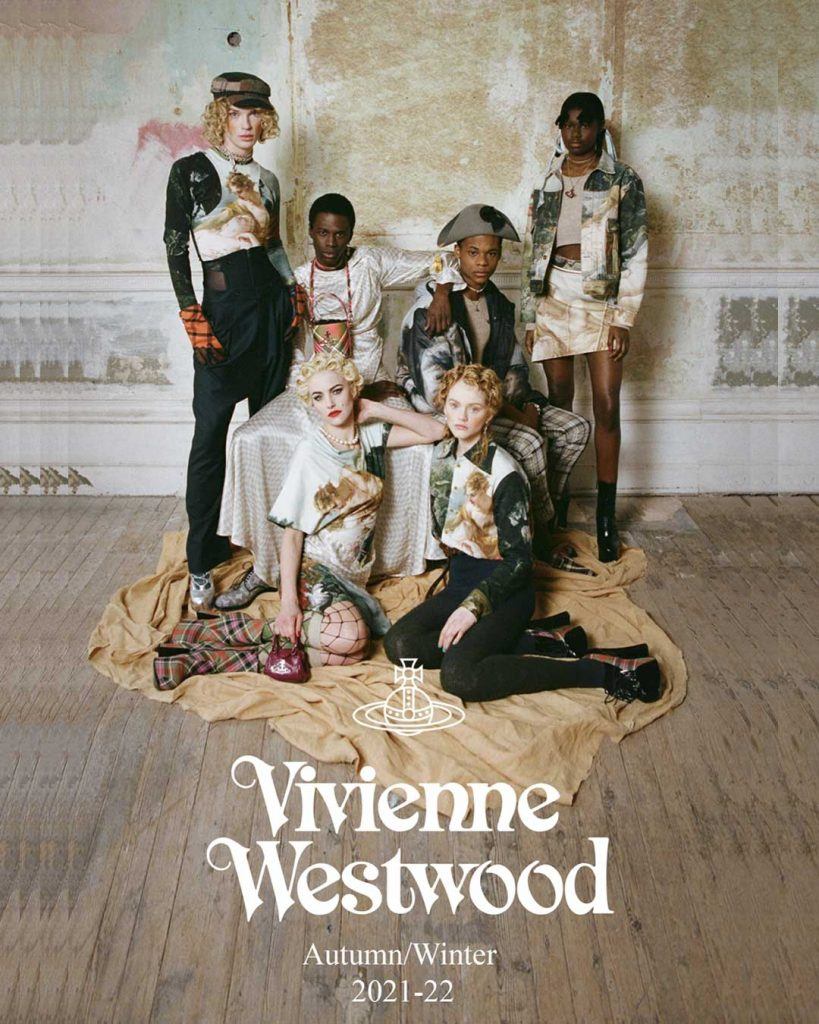

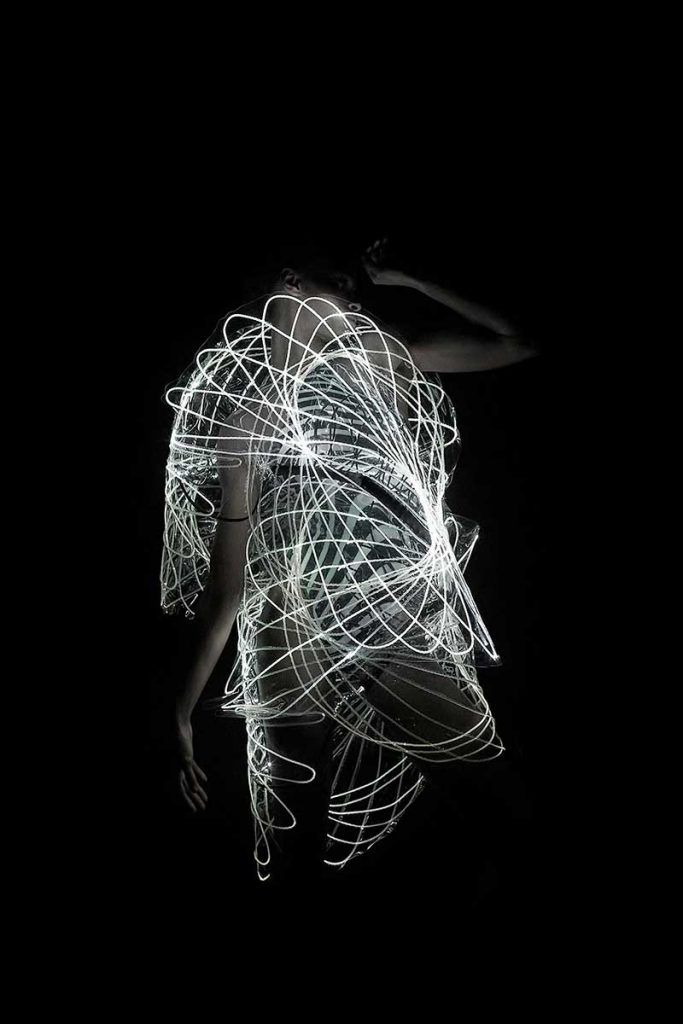

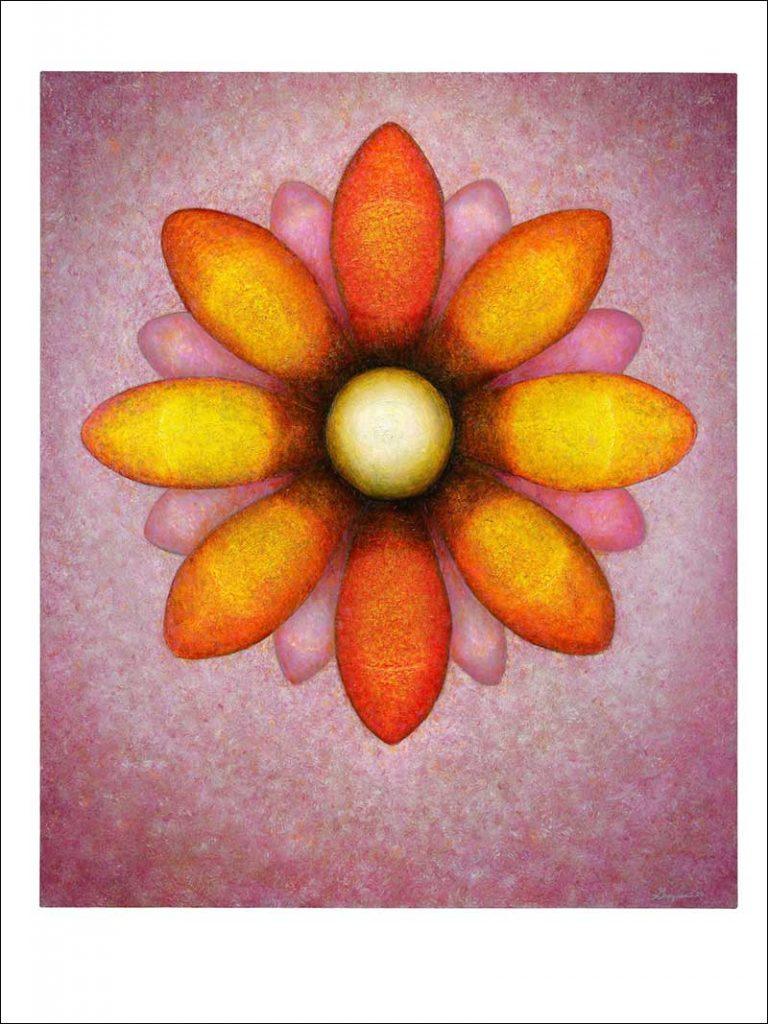

“Pandemic Flowers” is a series of portraits of magnified surreal flowers which seem life-like. There is a modern starkness about them, a deafening silence. From a distance, they appear so three-dimensional one might mistake them for sculpture, but as you approach, the solidity dissolves.

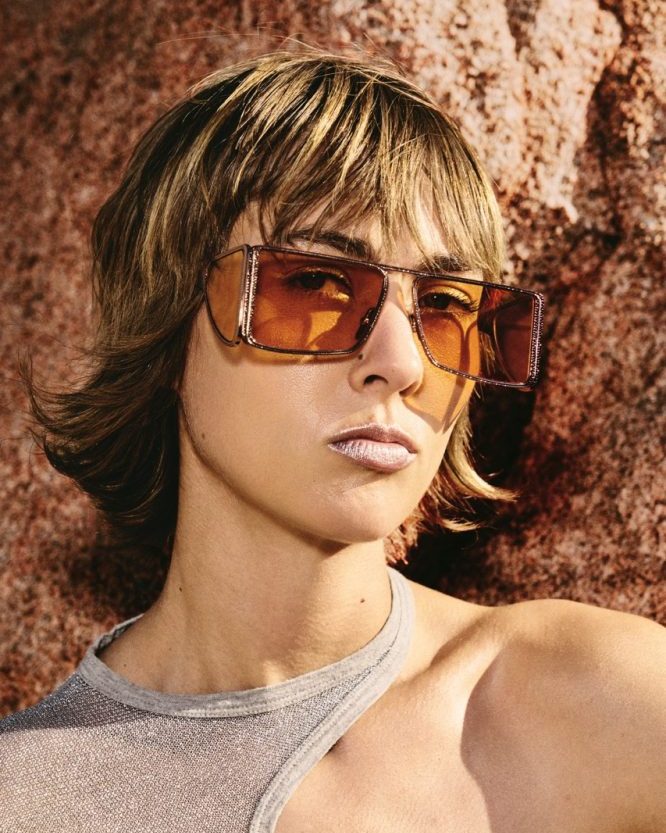

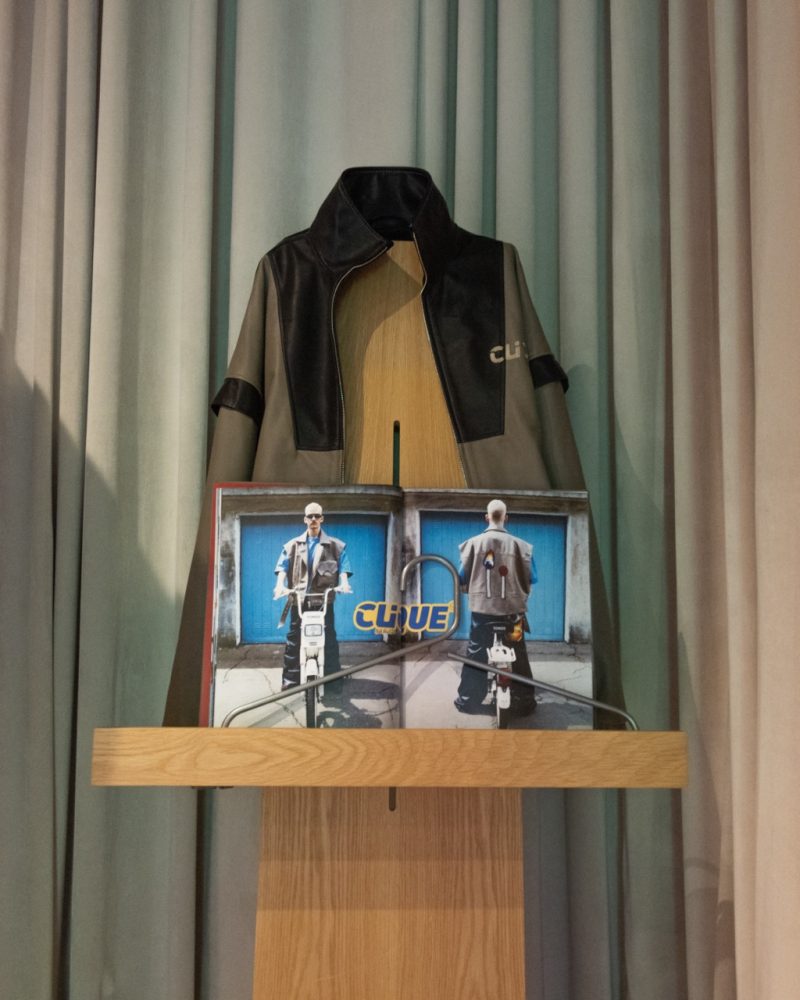

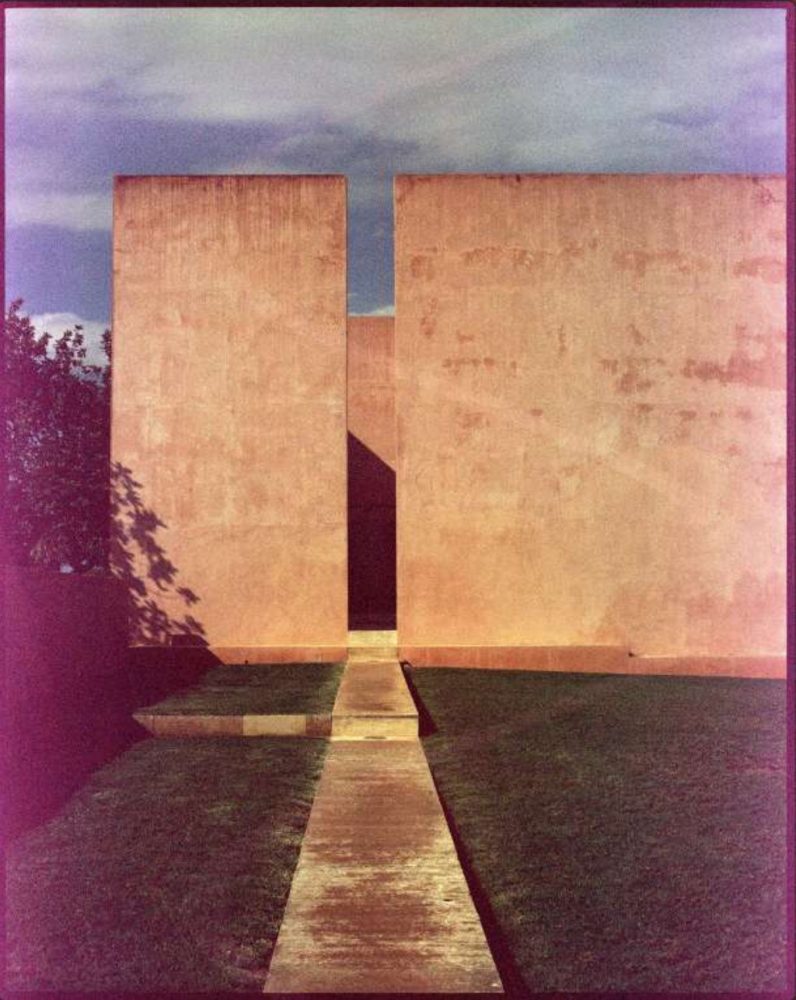

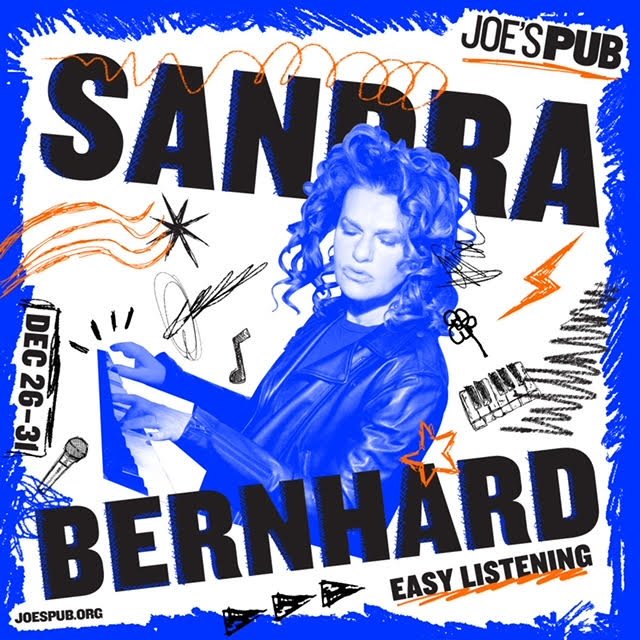

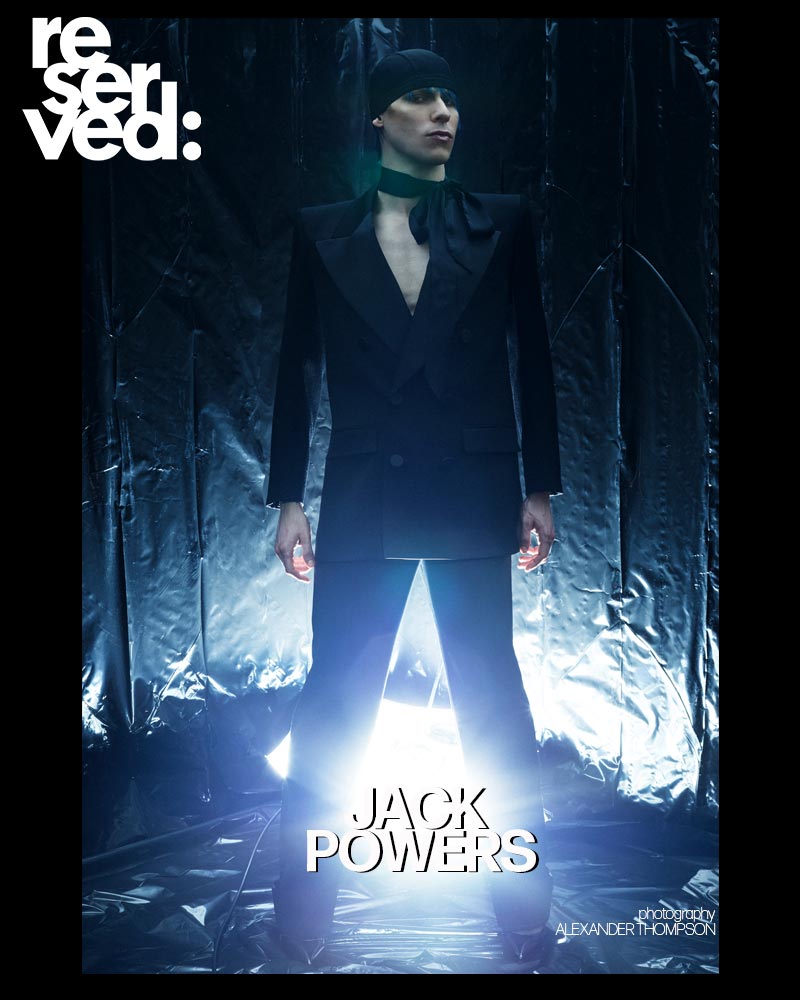

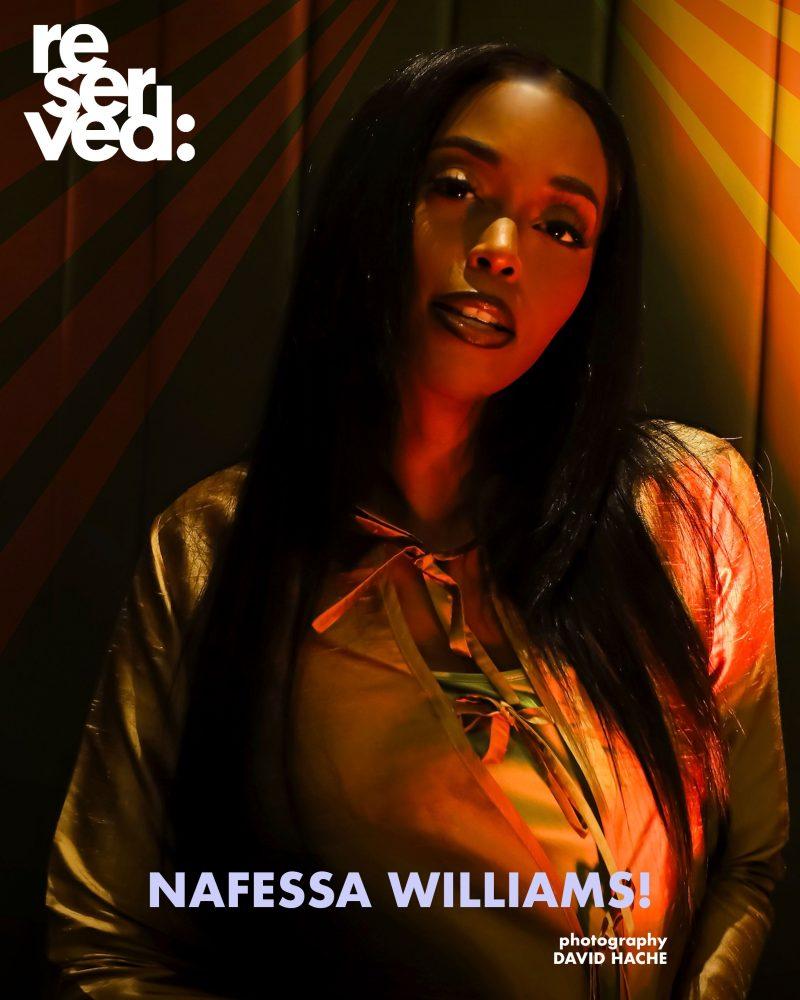

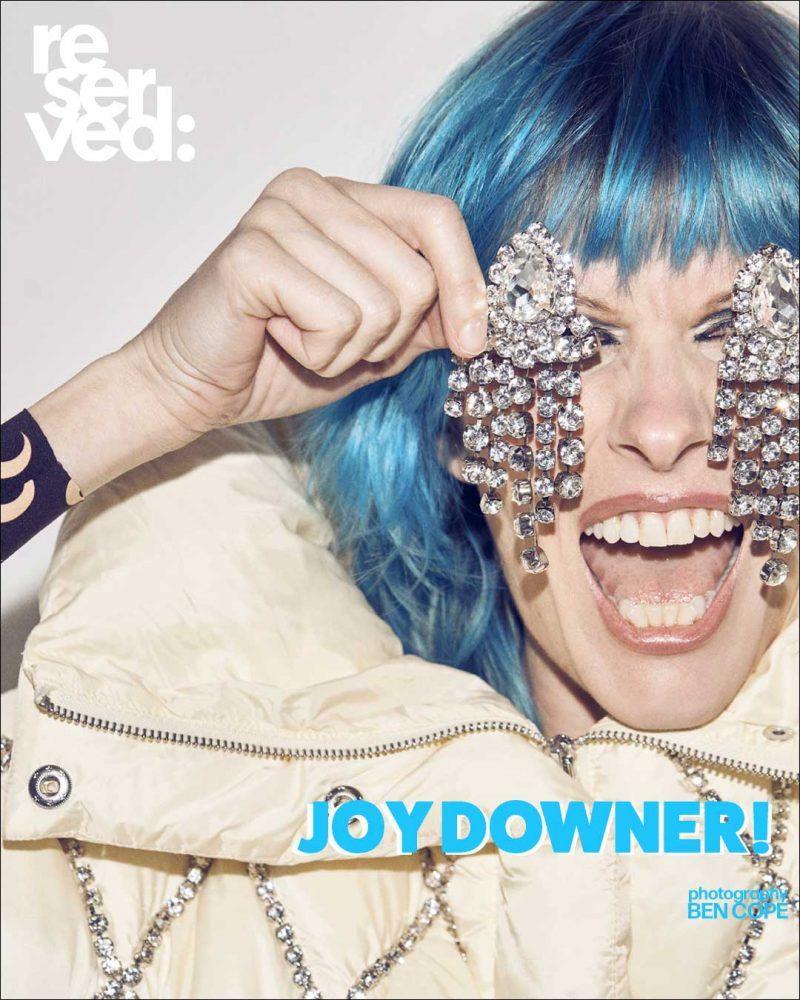

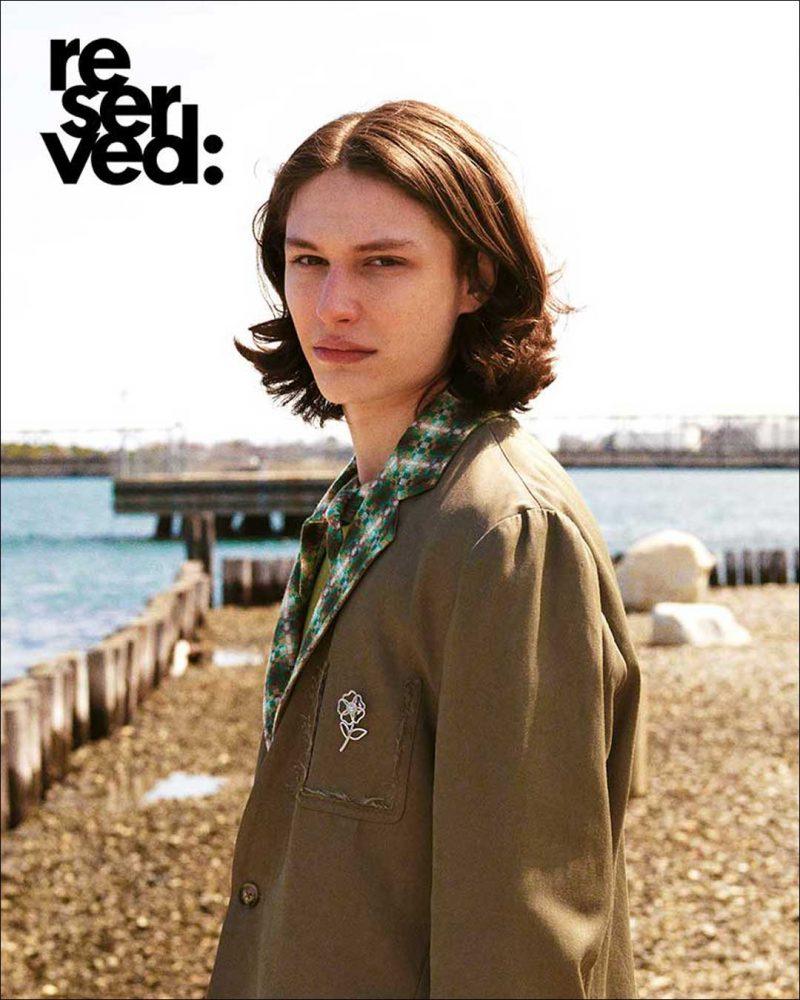

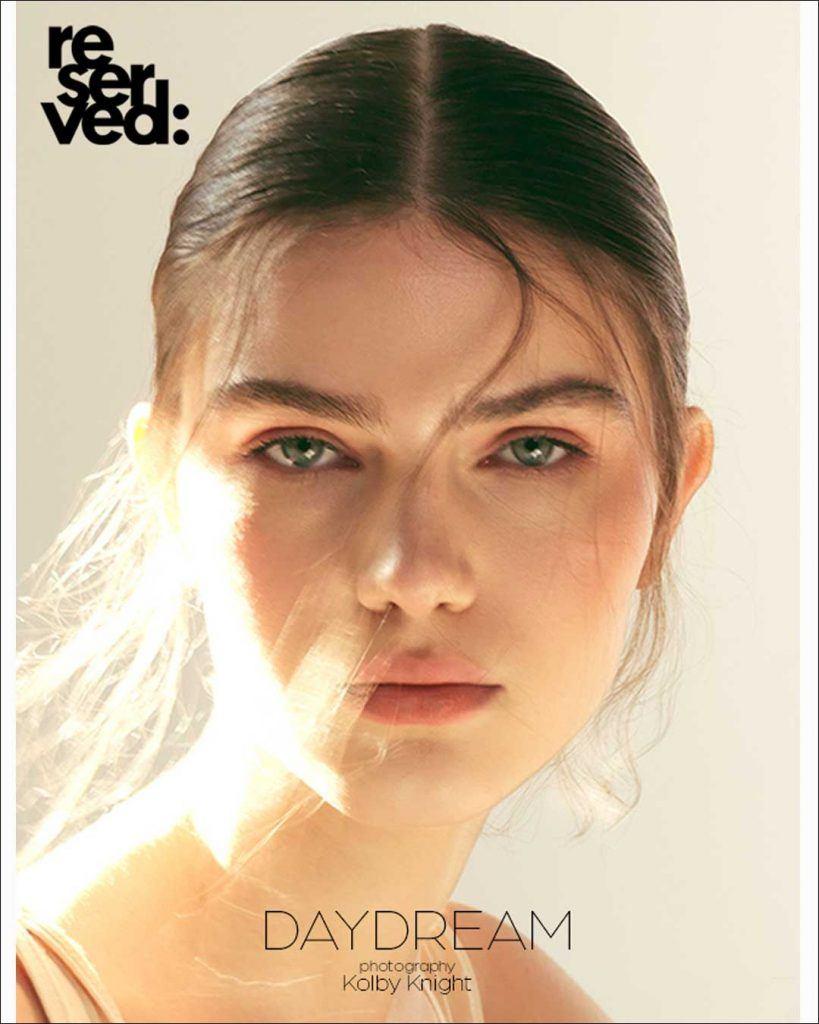

16 Petals by Neil Grayson, 2020. Oil on canvas, 72×60 inches. Courtesy of EYKYN MACLEAN GALLERY.

This new body of work is, in some respects, a significant evolutionary adaptation of his previous work, which derived power from chiaroscuro techniques used by Renaissance masters, predominantly shadowed canvases with relatively intense light in the center, light created with dense, thick paint and saturated with glazing. That style is consistent with the idea of the artist as a tragic Promethean figure, the bringer of light in the darkness, at a time when the most important thing for humanity was gaining knowledge.

Grayson’s 2020 vision made him realize a shift in his approach to painting that resonated with our cultural shifts. The challenge today is not a lack of information. We have too much information, too many choices, and not enough time, he says. The challenge today is creating selective filters which are needed for the storms of data we’re exposed to on a daily basis. Visually this means creating “a sense of depth in the light.”

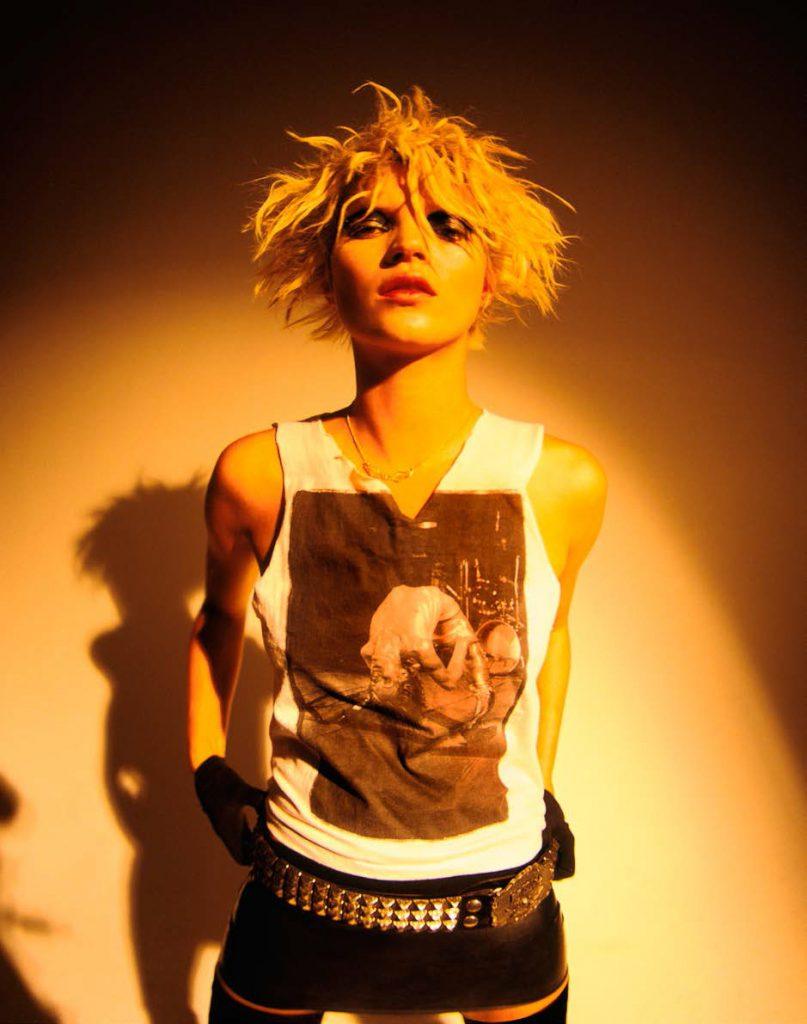

You call this series the Pandemic Flowers. How did the lockdown inspire you? What about the protests right outside the door of your SoHo studio?

I paused in front of a blank canvas during the lockdown. I felt the larger sense of the word “pandemic,” which derives its meaning from the Greek “all people.” I wondered, what is so ominous that it affects and eventually condemns everyone?

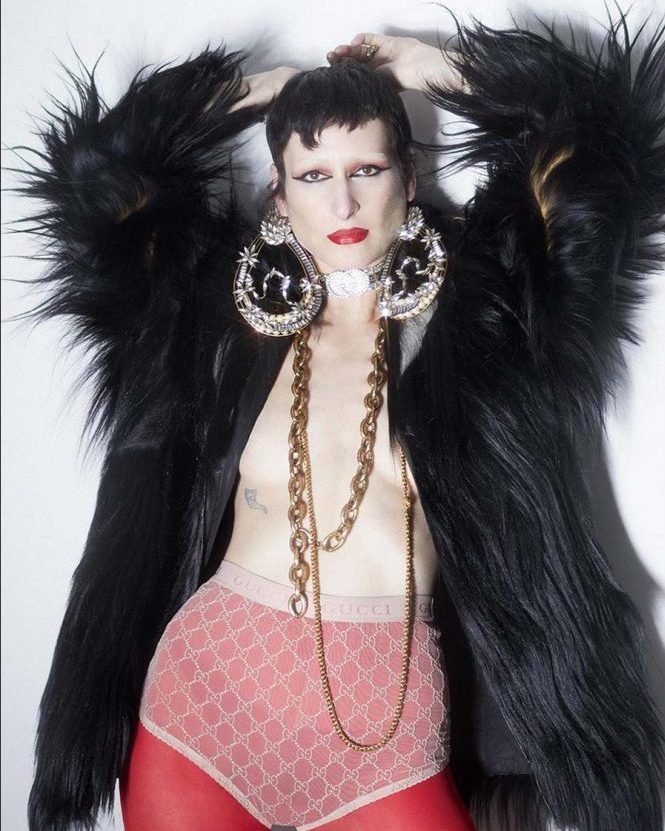

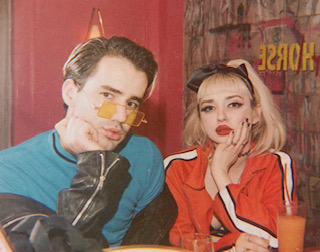

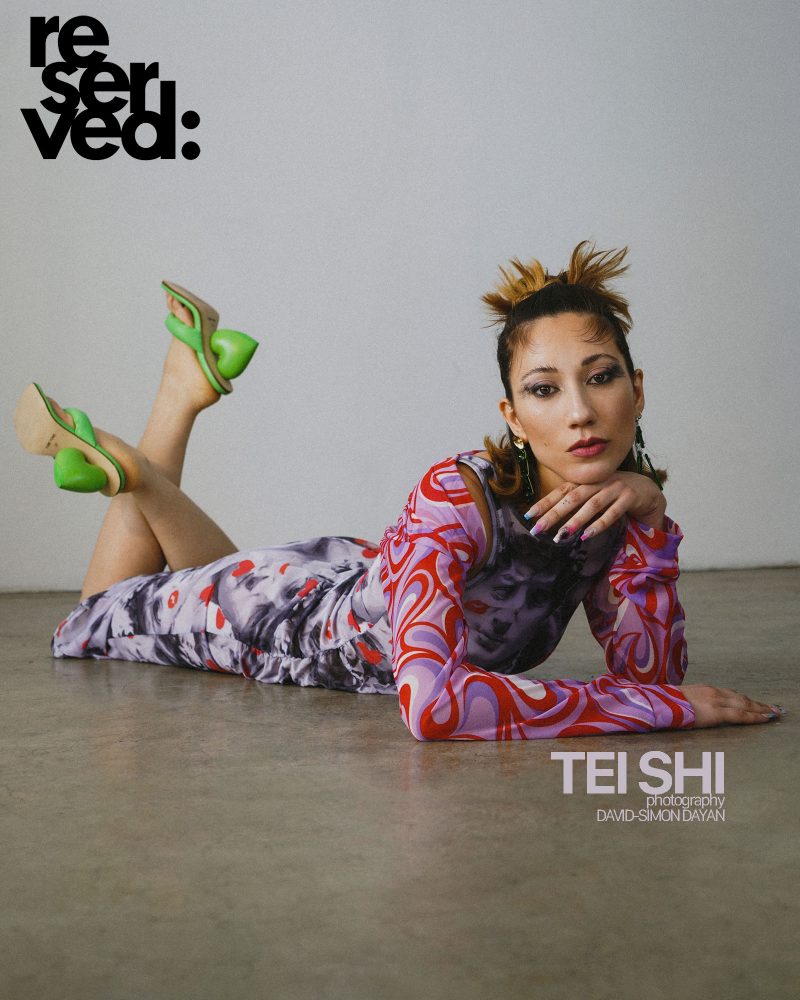

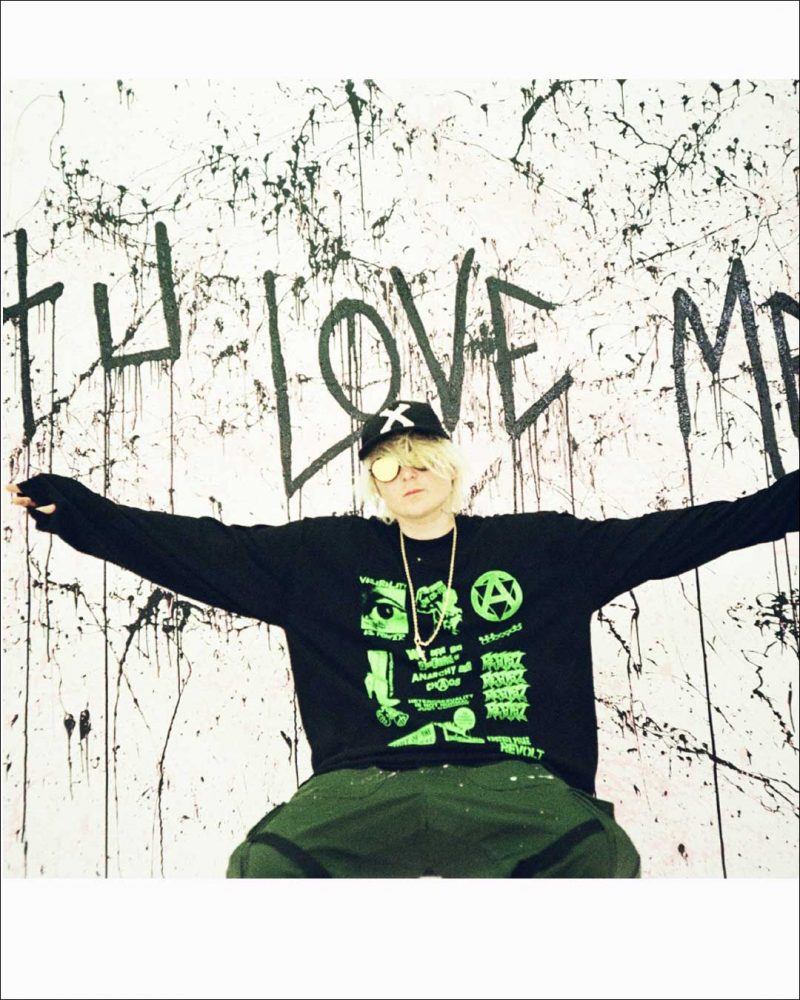

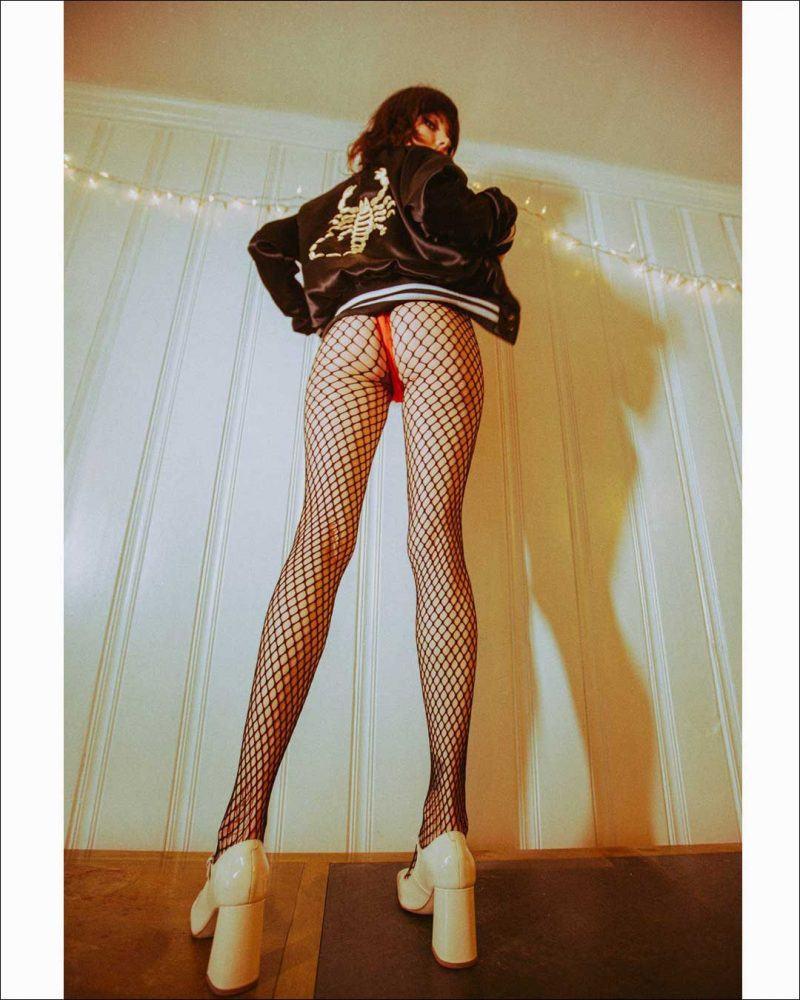

- Pandem 6 by Neil Grayson.

- Whisp by Neil Grayson.

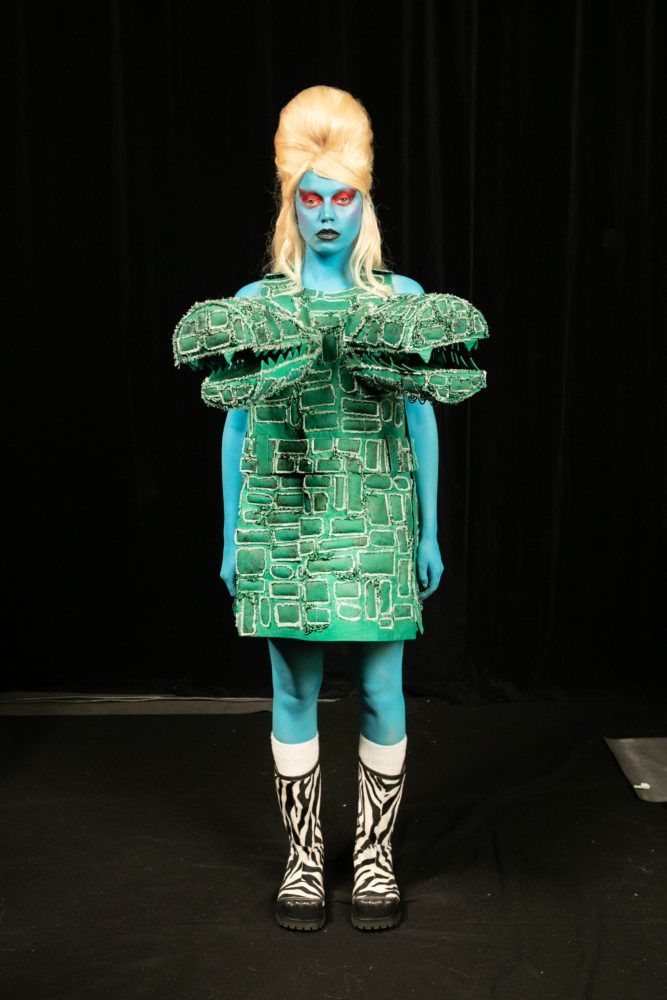

What bothered me most was the sudden feeling of hopelessness, I thought, how is this possible? And in that brief moment, having no answer, I chose to remember what it felt like to be a child before I knew too much. I chose to remember what it was like to believe there is a surreal world where anything is possible, without limits. I could go to Mars with SpaceX.

I wanted those chemicals to rush through my brain, and feel that drug our DNA sends us. And my mind landed in an otherworldly garden, where unknown flowers with the spherical cores, resembling the cones of 808 speakers, emanated sound and vibration, the pulse rippling the petals.

Although you used a brighter palette than you do in your previous work, there does seem to be a different kind of depth.

It’s funny, when I was very young, a teenager, my work was darker. I was obsessed with chiaroscuro, Rembrandt’s self-portraits, the fire-pit in Goya’s The Forge –you know, really dramatic shit. But old masters already own low-major-key painting, and the real challenge today, to me, is to create new content and re-imagine high-major-key, developing language that reflects the current information overload.

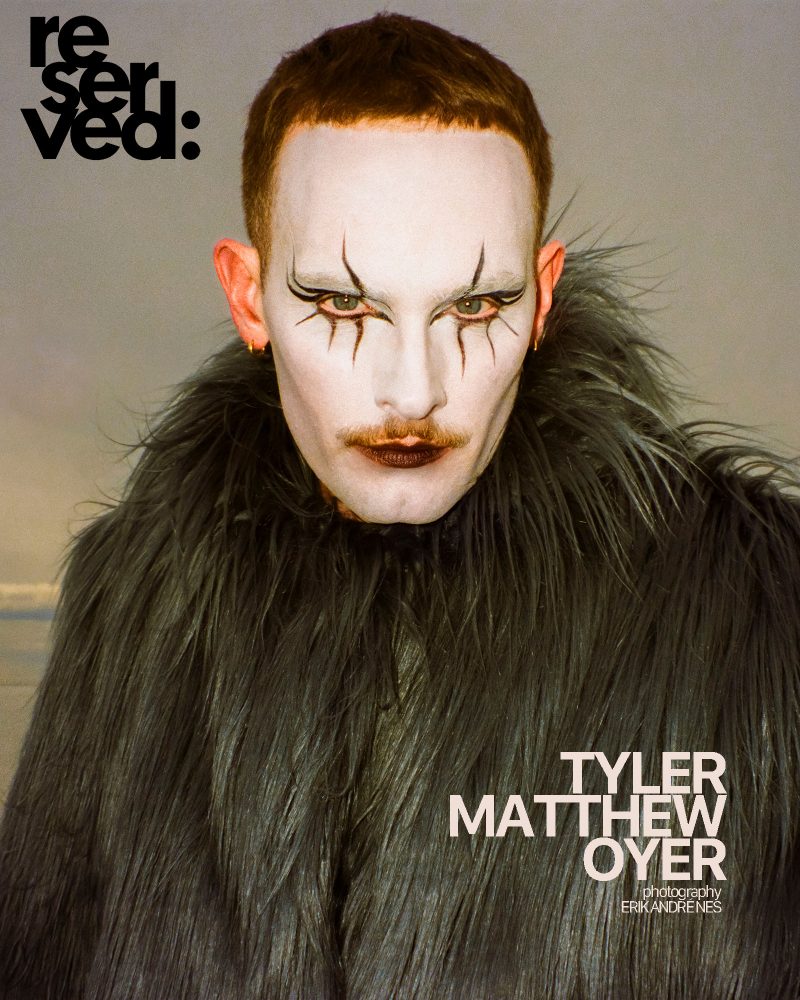

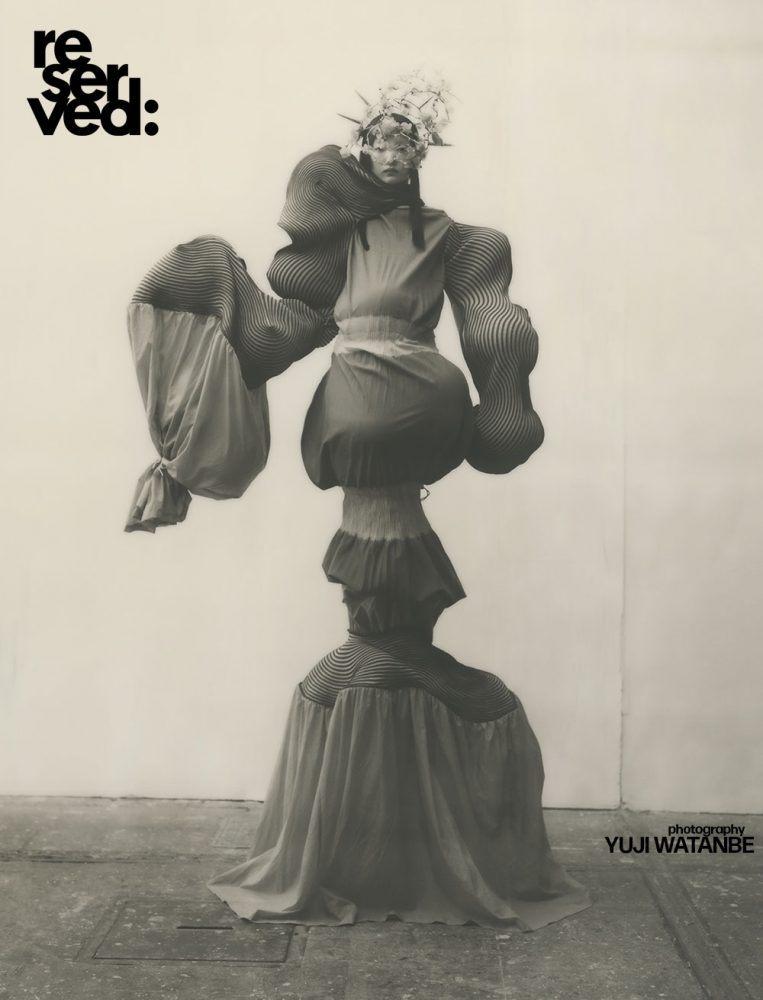

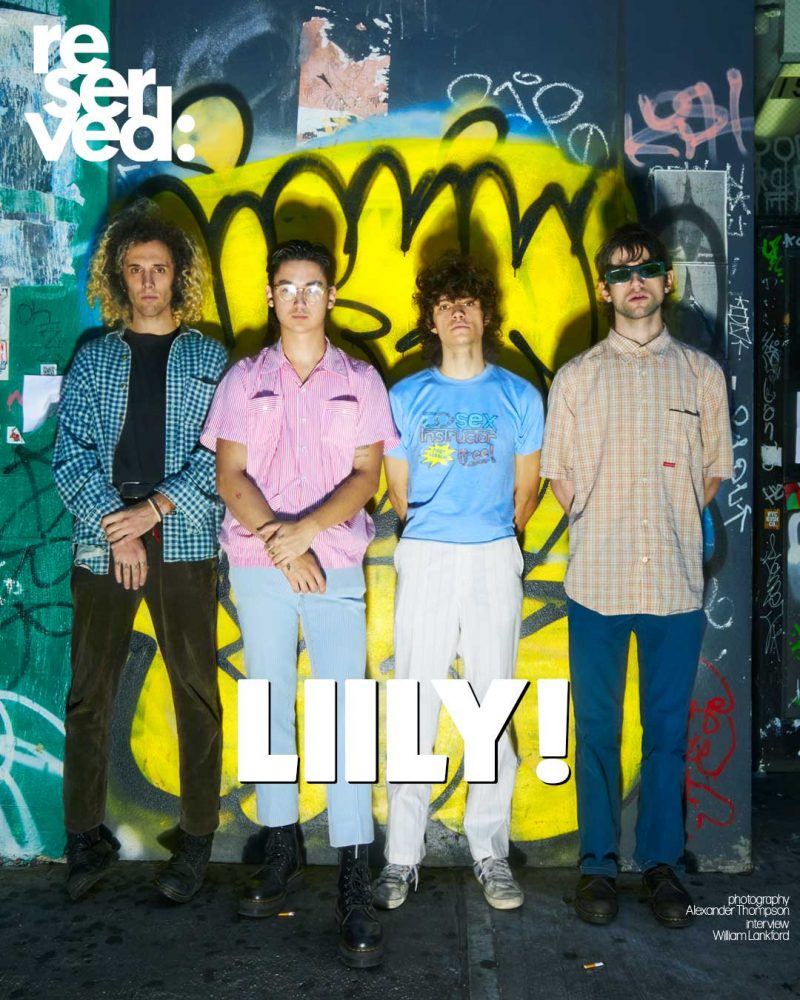

- Max Poppy by Neil Grayson.

- Sunflower by Neil Grayson.

To explain, in low-major-key painting, painting the larger environment is shadow and the focus is light. In high-major-key, which is hard to do, the larger environment is primarily light and shadow is the focus. Turner nailed high-major-key in his more abstract works, not so much the articulated ships and detailed cities, but the storms. Since everything is in the light—nothing is hidden—high-major-key lends itself to distraction, too many choices, which feels like today’s world.

In this parallel to how we exist today, we need filters. The task today is to find content in a wasteland of well-lit data. A few hundred years ago, someone might take great risks to smuggle a controversial book into a country to spread a dangerous idea like equal rights. I think of that as a low-major-key struggle. Today we often miss life because all our time is spent swimming aimlessly in pools of data due to our numerous personal devices. I love irony.

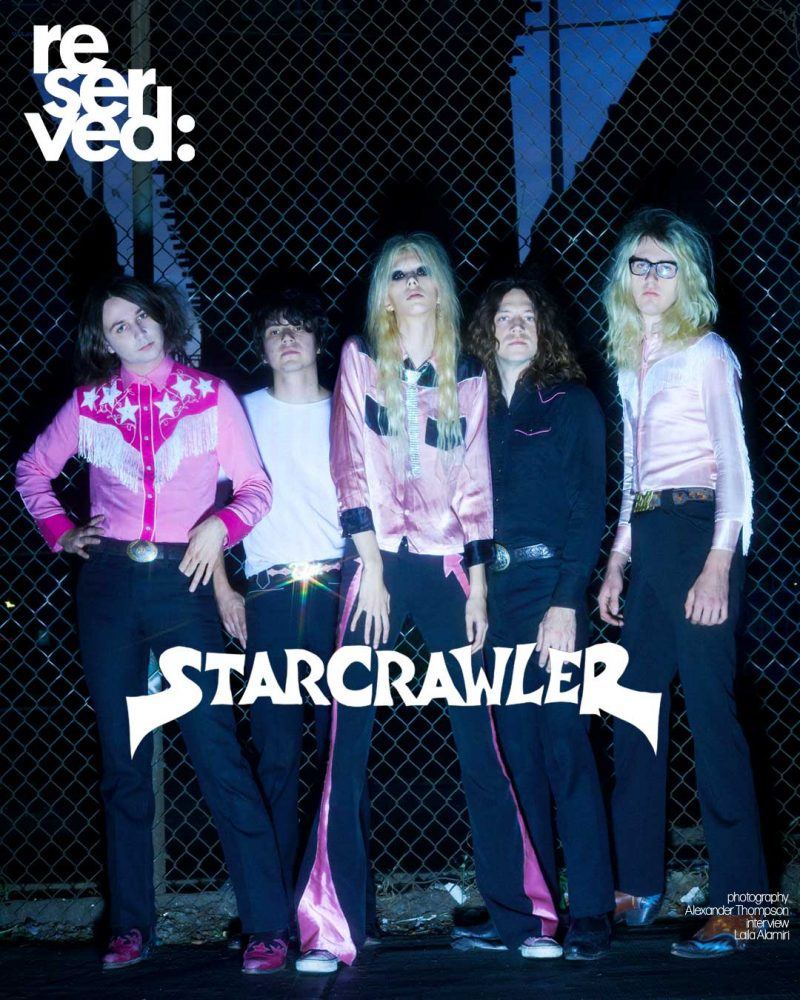

- Yellow Pandem 7 by Neil Grayson.

- Pandem 8 by Neil Grayson.

When I look at these paintings, I see a painter who has an obsession. The detail. The magnification. The time that went into these. The deliberateness is almost insane, would you agree?

Insanity would be doing the same art over and over, and once in a while, innovating by accident and not trying to recognize how the accident actually works in order to use it. You’d have no growth. Innovation comes, not from insanity, but from discipline, which can be very hard for an artist, like me, who indulges in poetic distractions. The deliberateness is what’s different.

I know the story about how, as a teenager, you copied Rembrandt’s 1660 self-portrait live at The Met. When you finished, the security would not let you leave with your painting because they could not tell the You had to wait for the curator to verify that the original was still on the wall. How did that experience affect you as an artist?

Since my tendency is to be not very disciplined, I’m very fortunate that I forced myself as a teenager to learn everything I could about classical painting. Because my technique is second nature now, I am free to spend my energy on concepts.

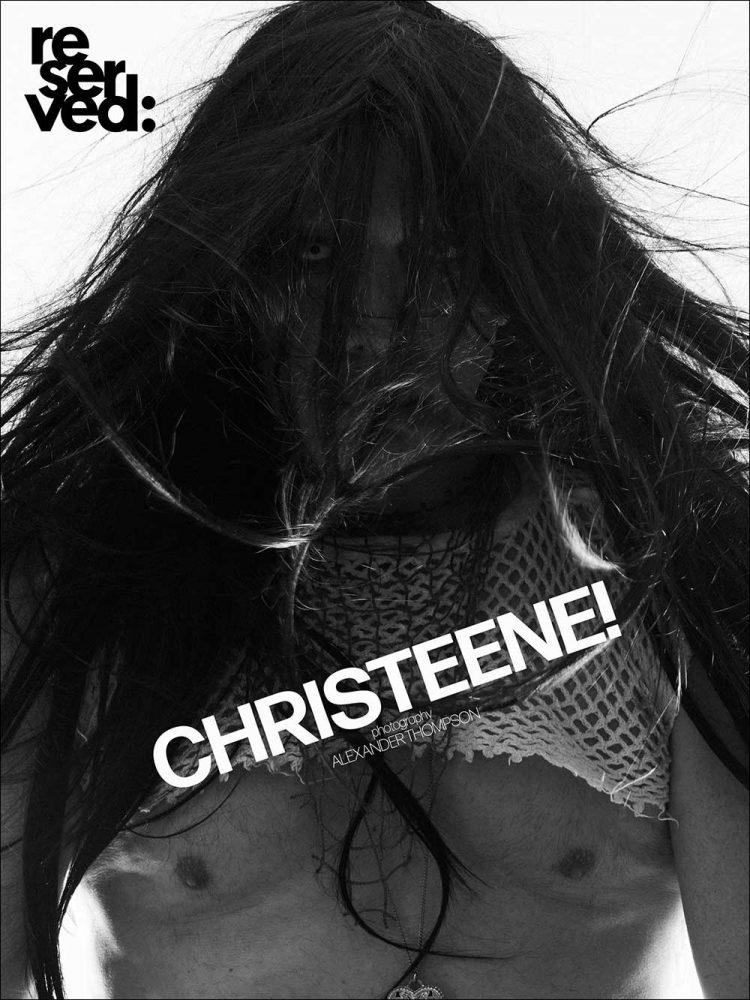

White Moon Lily by Neil Grayson.

You mention this is only the beginning of this series, what do you plan to do next in this vein?

Several years ago I painted one of my favorite pieces, called The Blue Boy, a young boy walking in an ice storm pauses before a hill. The blue boy’s persona now lives in the Pandemic Flowers. It’s a precursor. The flowers resonate the sound he discovers. The child’s curiosity is the future. difference between yours and Rembrandt’s. https://neilgrayson.com/