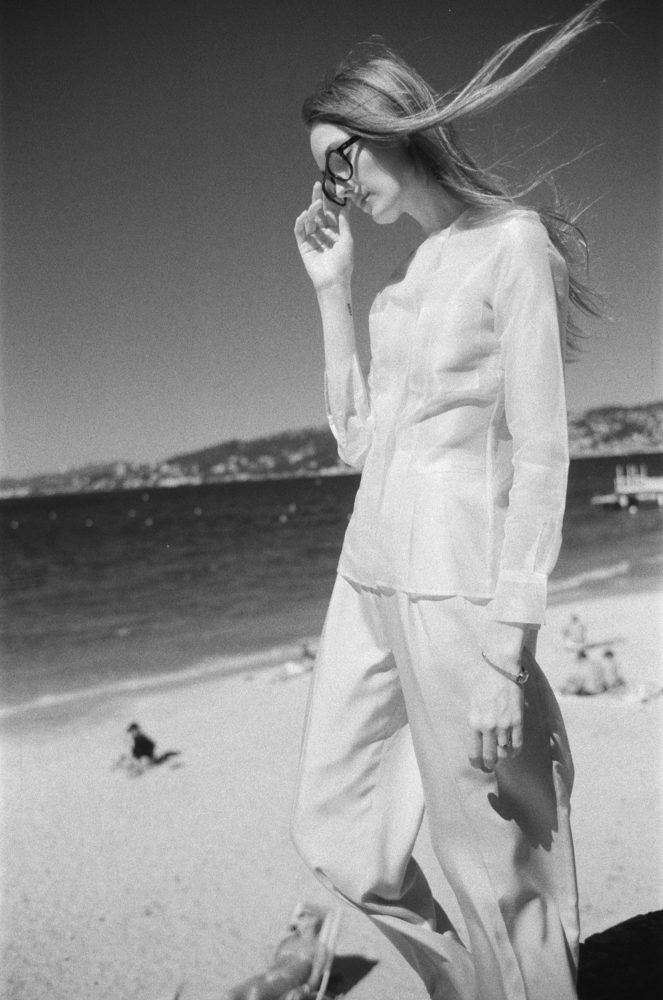

The process of grief has always been a purely individual experience met with highs to lows, delusions, anguish, and the various gradients of feelings. Ema McKie’s poetic vision for this human experience in “A Stab at Heaven” distills and expands on the various thoughts and paths which grieving goes through. From its moments of anger and bribery to peace and possibilities, it’s just one of the many narratives which has incorporated this very sense of emotion. Directed by Mark de Paola the film’s visuals complement and amplify the expanse of the emotional turmoil. The film itself lives as not just a piece of celluloid, but as an obstruction of mourning and the intricacies of intimacy. Inspired by Ema Mckie, personal journey after losing her fiancé at the tender age of 19 the long-form work has been one which was met with acclaim and catharsis. we speak to the Ema McKie on the creative process of dissecting the various emotions to create a coherent division of a modern road trip film.

Tell us more about the background of “A Stab At Heaven”. You had mentioned it was based on your personal experiences and that the story references what happened to you ten years ago. What was the process like from its inception into realizing it as a film?

Yes, the story comes from a period of time when I was 18. I had just lost my fiancé to suicide and was searching for a way to find myself and him through the chaos of grief. Initially I had shared the story with Mark as just that and not a pitch. We were driving back from shooting in Palm Springs and this long story came out of me as sometimes happens with close friends. After a long pause, Mark broke the silence by telling me that I should turn this into a film, forever a storyteller. A prospect I had never considered. I responded in saying that the only one I’d want to take on the project was him. At the time he had set his filmmaking aside to focus on his fine-art still work. His idea struck something for me. I’d been studying acting under Marjorie Ballentine for a while at this point and working on a few film projects, something I’d found a lot of life in. It was a world I wanted more of. We left the conversation as simply a story and a thought, but something must have struck a chord with him too. Not long after, we came back to the conversation and got to work on a life rights agreement. That was five years ago. This whole project has been filled with moments like this of serendipity and the forces that be. To be frank, we didn’t have much of a choice but to let that move us forward, and if we did, it was a choice that I’m grateful for.

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

“A Stab At Heaven” features a heavy amount of poetic voice overs and gestures. What was the script writing process? Can you share a bit about its unique stream of consciousness narrative structure and about your personal self edit and refinement?

Not too long into development, Mark suggested I take down some notes as things came to me. We were working closely to develop the story through my memory and his writing and storytelling. I switched gears and started thinking on the page. I had written a lot of poetry in my younger years and once I got started it just kept coming. It felt right to start that up again as I had been writing during that time period and had stopped shortly after this story takes place. Sixty three pages of writing later, Mark decided to deconstruct the cinematic narrative, pivoting to the internal stream of consciousness of my writings. In this tradition of writing, we left it unedited, embracing the whole of how truth is at times messy, un-actualized, layered with emotion and self perspective. We didn’t want to polish this, giving way to the honesty of how things are on the way to working through grief and depression.

How did you get involved with working with Mark de Paola, his visual language exceptionally matches your words.

We became friends through my husband Bil Brown many years ago, a connection that was formed through the photographic community. We spent many seasons together in the fashion week circuit, shooting and sharing company wherever we were in the world. There is a great understanding and beauty in his work that I’ve always been drawn to, and I just never stopped asking to shoot. It’s been such a gift that he never stopped saying yes to more projects, and as always, there are new things on the horizon that I can’t wait to share.

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

What was the significance of the initial scenes in Paris? Were they a representation of being able to find a sense of solace?

I had been in Europe the week before John (my late fiancé) died, and it has always been the landscape of the calm before the storm to me, followed by the limbo of knowing that, eventually, I would have to leave and face the reality at home.

The poetic gestures that are presented in the long road trip style of the film speak to the human experience. In what ways did you feel these sequences were used to convey your grief and depression?

We wanted to take the internal, the feeling of it all, and visually represent the things you hold in your chest, the way we run from that which we don’t know what to do with, the aloneness of the road. The way A Stab At Heaven was filmed really acknowledges that. We all feel things that don’t seem shared or appropriate for company, but that doesn’t make them any less tangible. It is human and it is shared.

Share with me about the process of shooting the film. How long and what lengths did you go to shoot it?

We gave ourselves full permission to create this film without limitations of need, and by that I mean that the understanding of the physical and mental space was always within that bubble of non-judgment that we had established from the beginning. Whether we were writing a scene of difficulty or shooting a 16-hour day in the desert, no one had to leave themselves at the door. I was able to leave the reliving of these scenes refreshed and seen, something you might not think possible when working through topics of suicide and violence. But it is, because the dark isn’t always something you have to shoulder alone.

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

- Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

The film seems like a singular character visited by all of these various ghosts and muses. Was the blonde girl featured a third of the way through the film a manifestation of your grief and depression? There was something of a representation of comfort yet hinting at horror.

That is very in line with how I feel about being in that state of mind, between dimensions and distanced from reality enough to be susceptible to what comes. Nico Young’s character Alex is definitely a manifestation of my grief paired with the memory of happiness. Looking back at the writing, I see how that kind of self reflection really translates as lost love in some ways. And the horror aspect is the truth creeping in. The fact that my character can never quite escape her reality.

Were the moments with Pedro Correa’s character Clay a confrontation, a memory, or a moment of closure?

I’d say that it’s all of those things. Pedro’s character is the embodiment of close friendship and a connection to the past, a person who connects my character to the memory of John. That moment is the peak of her grief manifesting in a moment of the internal colliding with the outside world. The subconscious and conscious worlds sometimes don’t have enough room to coexist.

What was your personal journey of finding closure in the production of the film, was it the act of making it or the completion?

Having such complicated experiences acknowledged in a project that gave them the room to be was incredible. I don’t know if I really believe in closure when it comes to grief but knowing that we made something so hard into such a beautiful thing gives me so much peace.

Ema McKie Photographed by Mark de Paola

What is next for the project, and where would you like to see this project go? There were moments which I felt the drawn out anguish that comes with loss and could see this being for those who need to express these sentiments, did you have a targeted audience?

We’re currently on the film festival circuit and searching for the right distribution partners. We created this film from my truth and the importance of maintaining the story and its essence, as we move into this next phase of sharing it with broader audiences. I’m really excited to share A Stab At Heaven. The private test screenings we’ve had have shown me the power in sharing my truth with others. It has been beyond moving and poignant to hear the stories of others’ grief and loss, and to find our collective strength as we come together. When we first decided to create this beautiful film I had no idea the impact it could and would have. As it progressed, the understanding of the responsibility we now have in starting this conversation through cinema became inherent. After living through that time, I can’t help but want to hold that in the light it deserves. Grace and respect for tragedy in hopes that though it may define us, it will not wash us away.