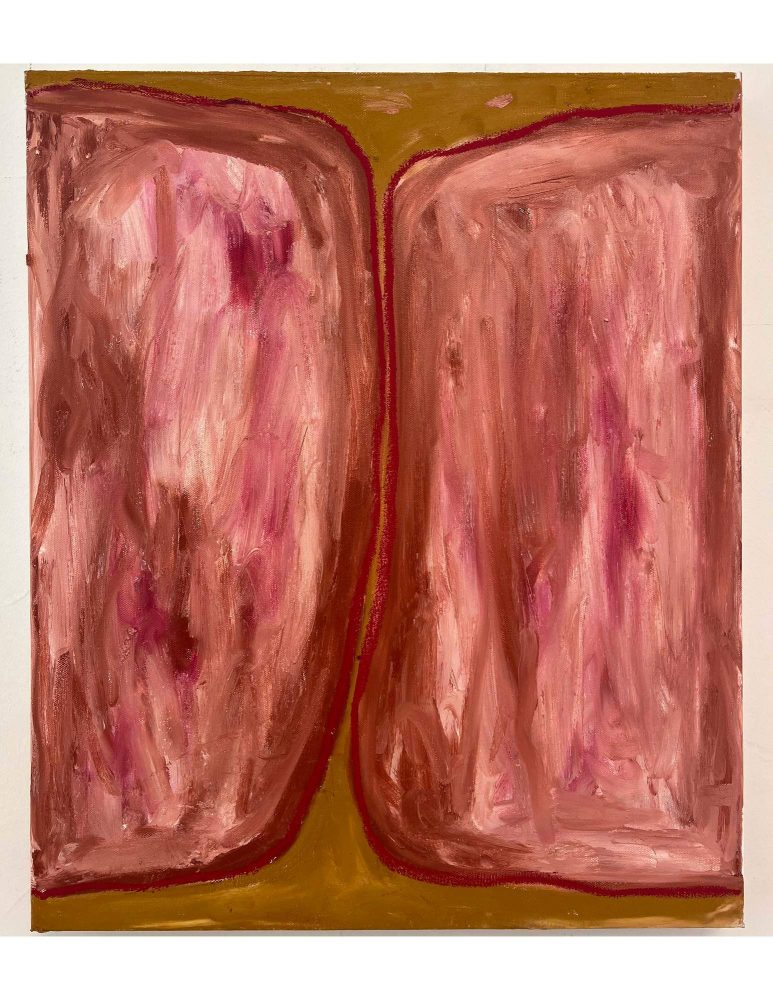

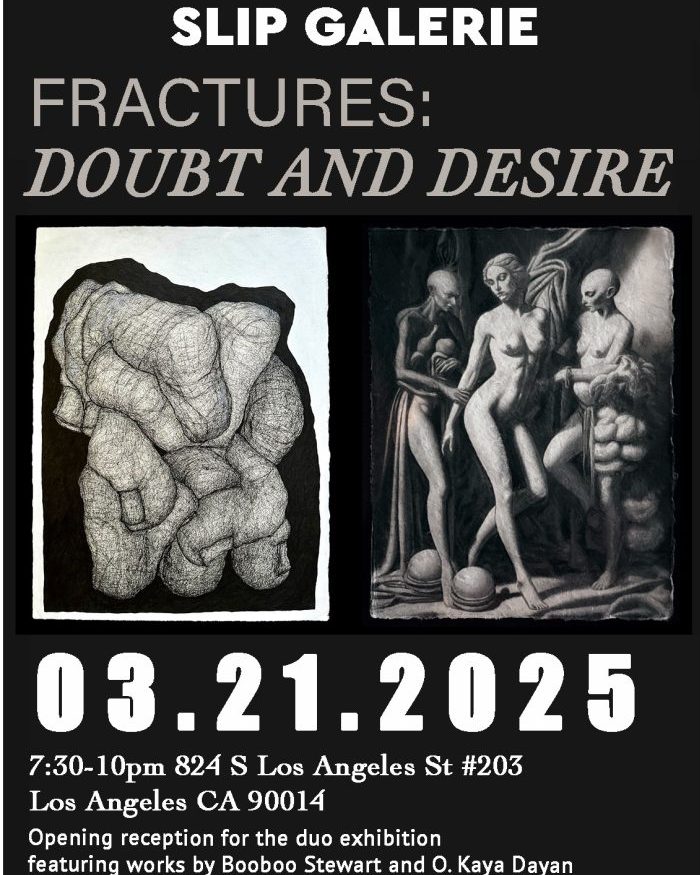

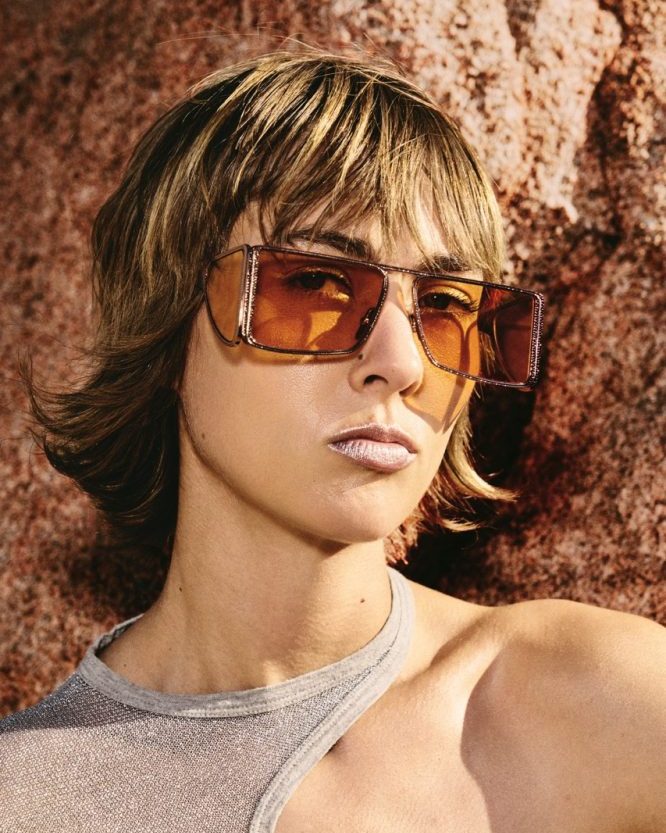

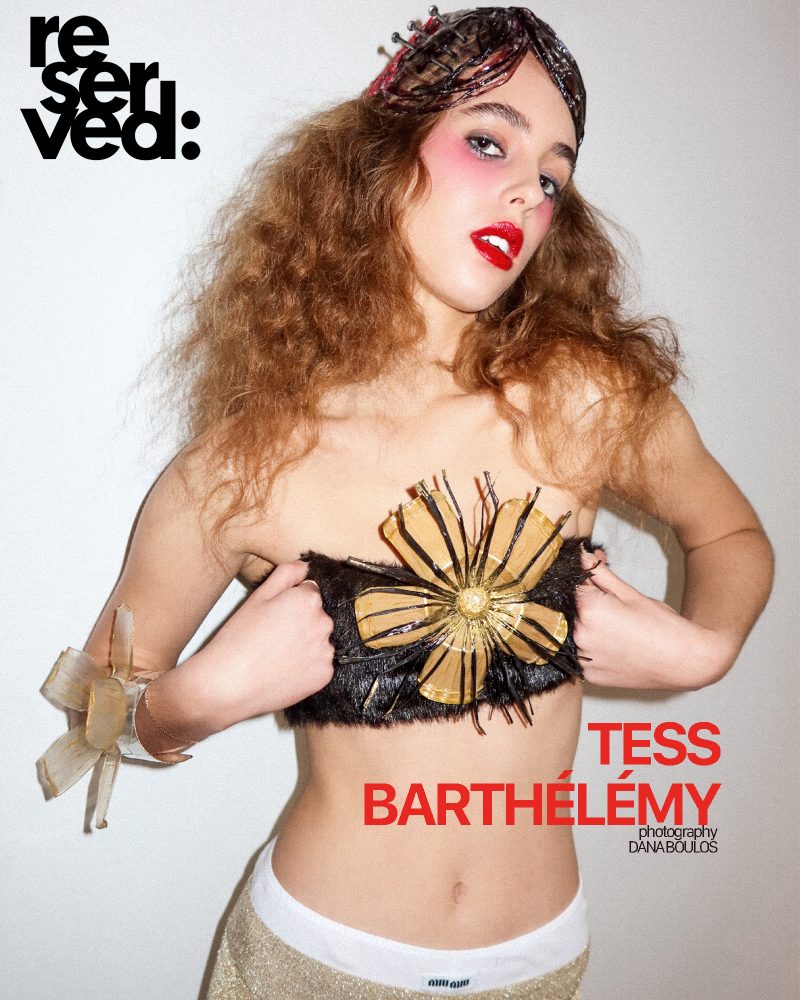

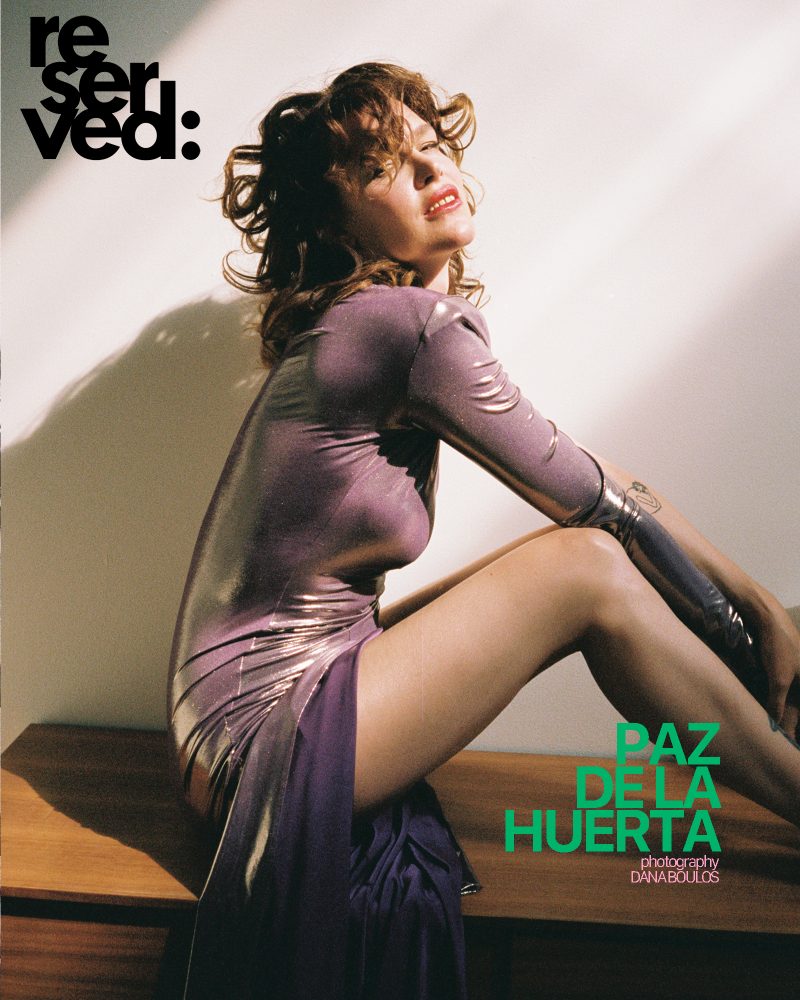

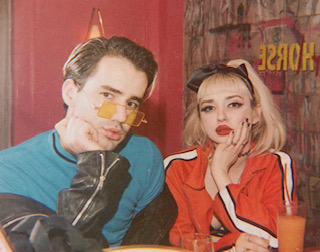

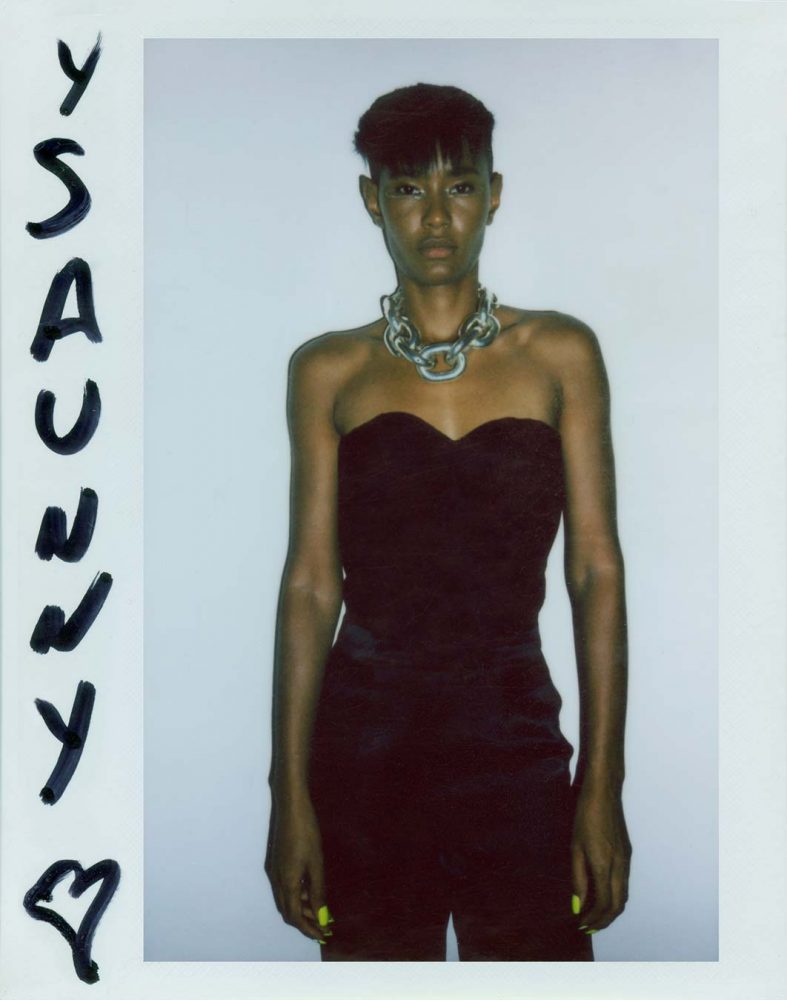

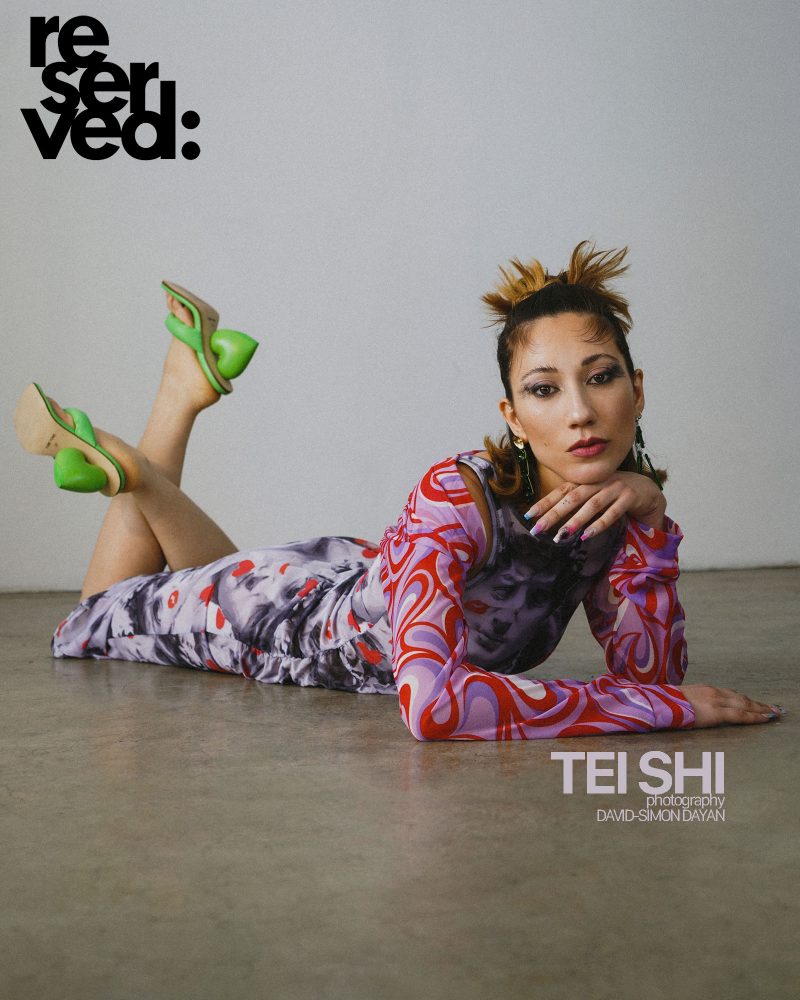

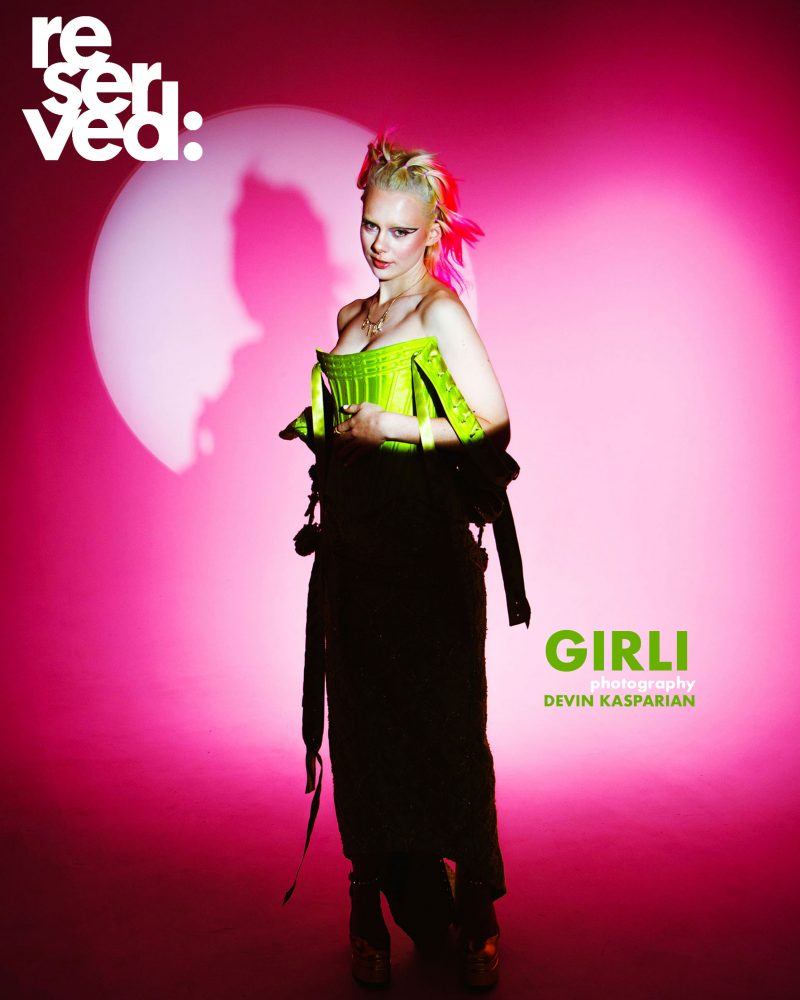

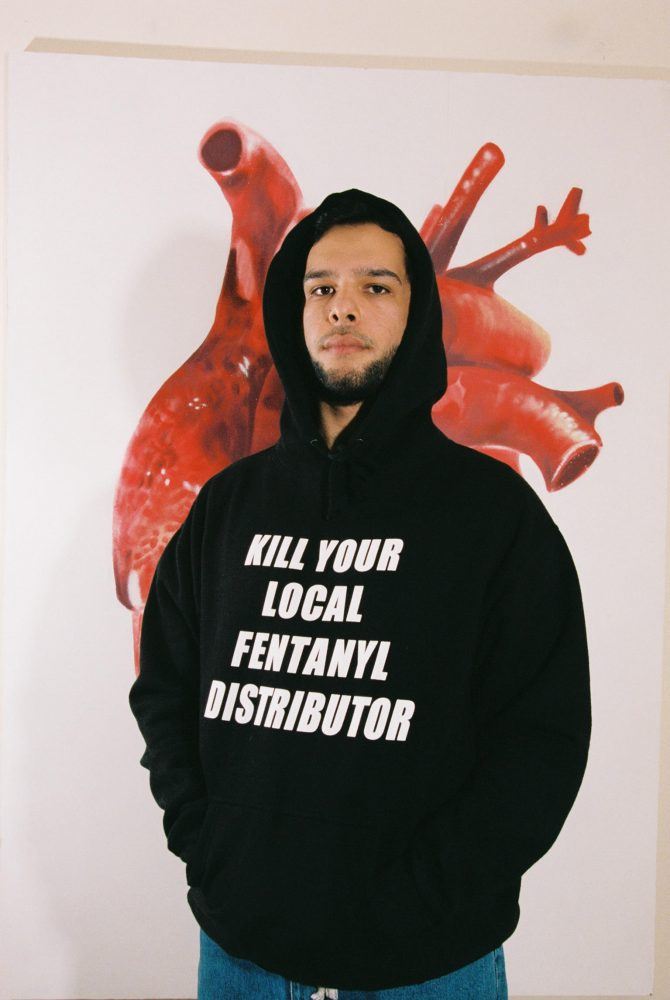

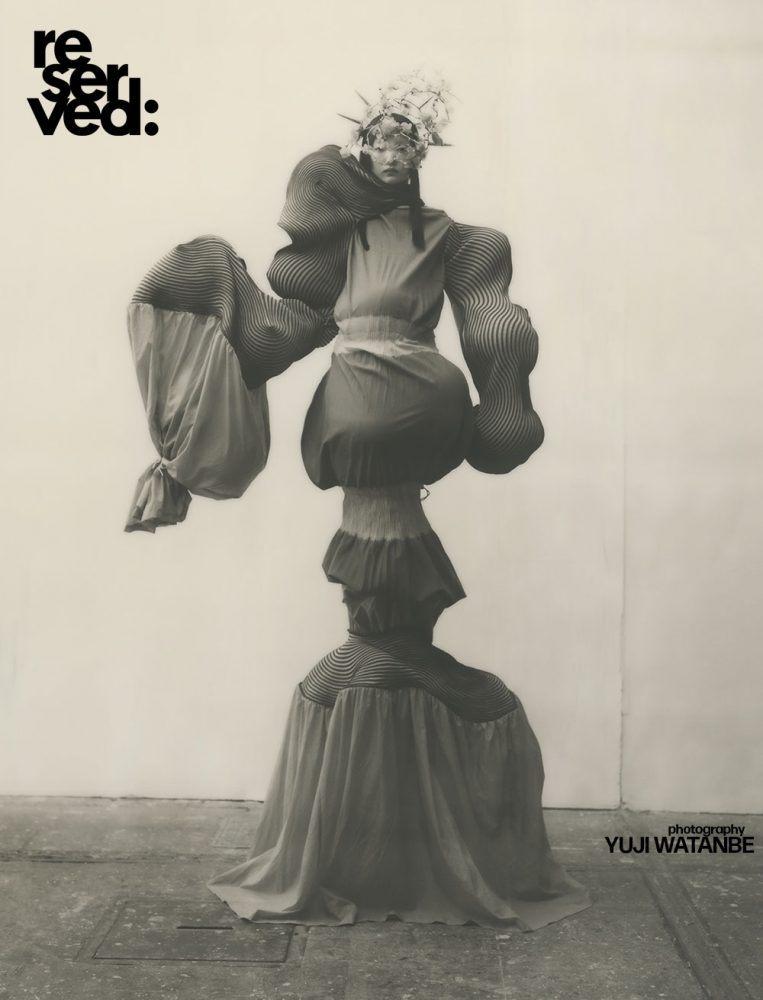

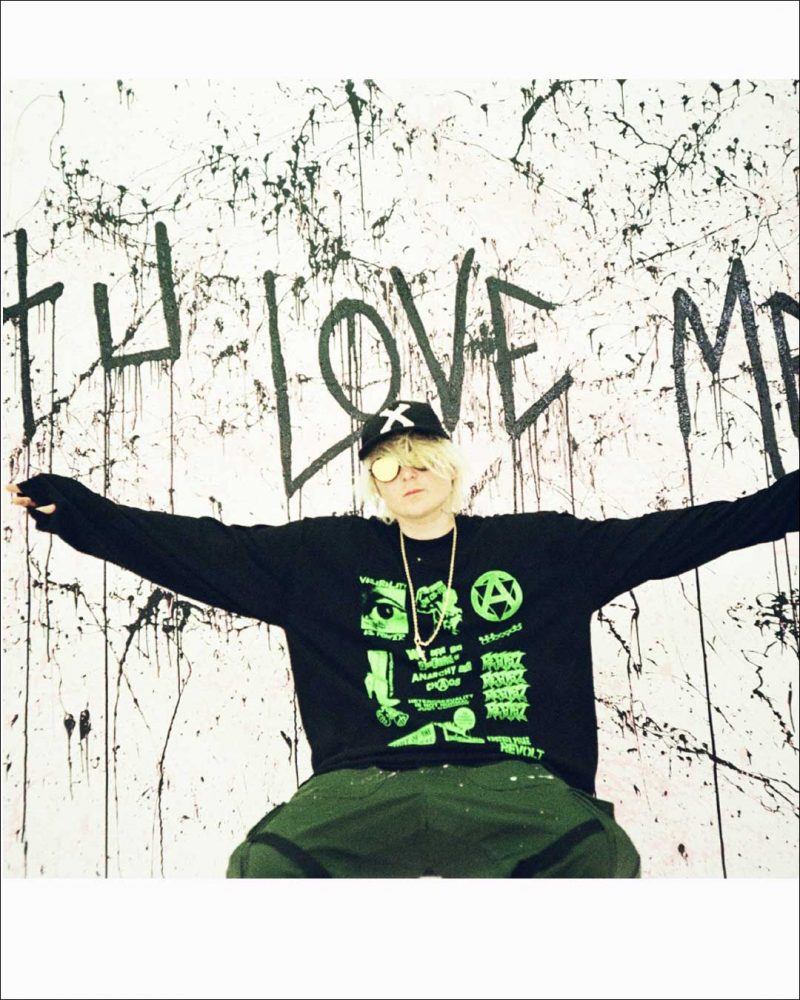

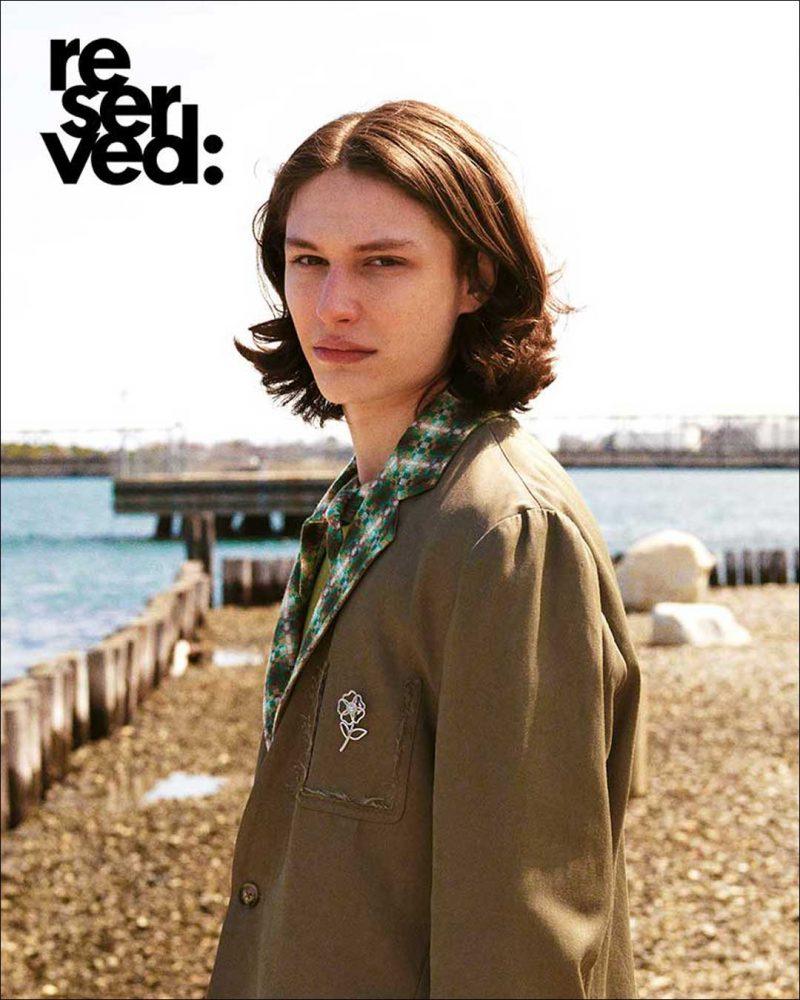

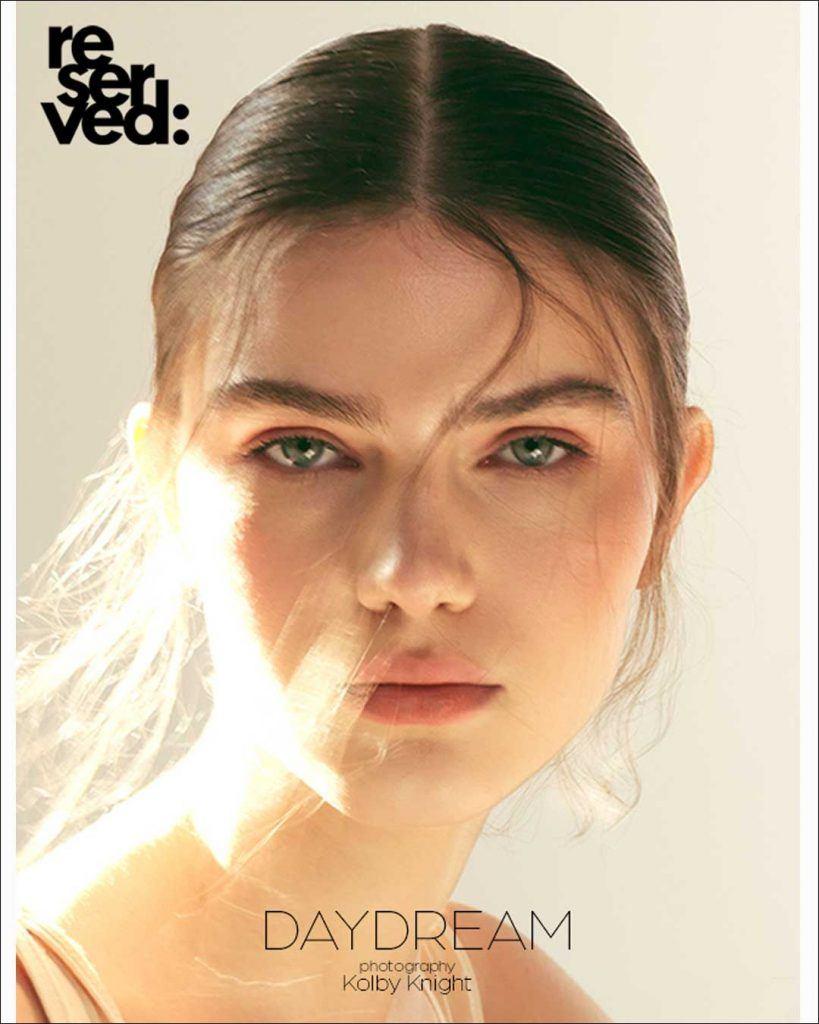

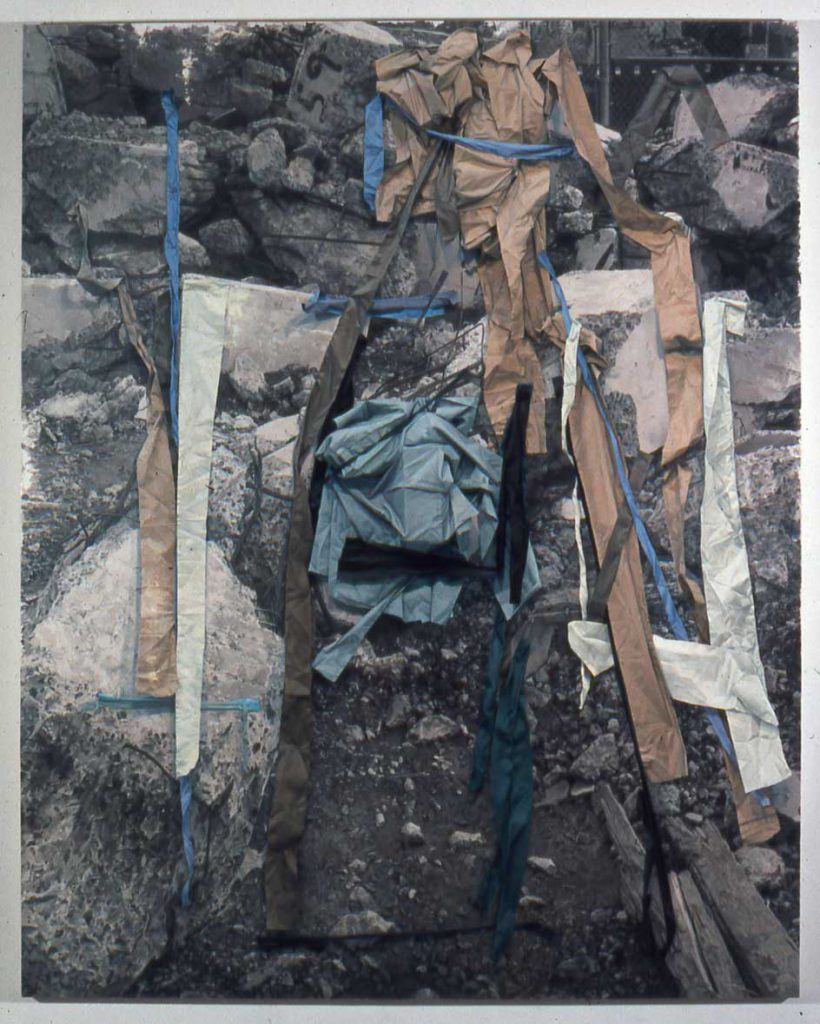

Alexandria Hilfiger

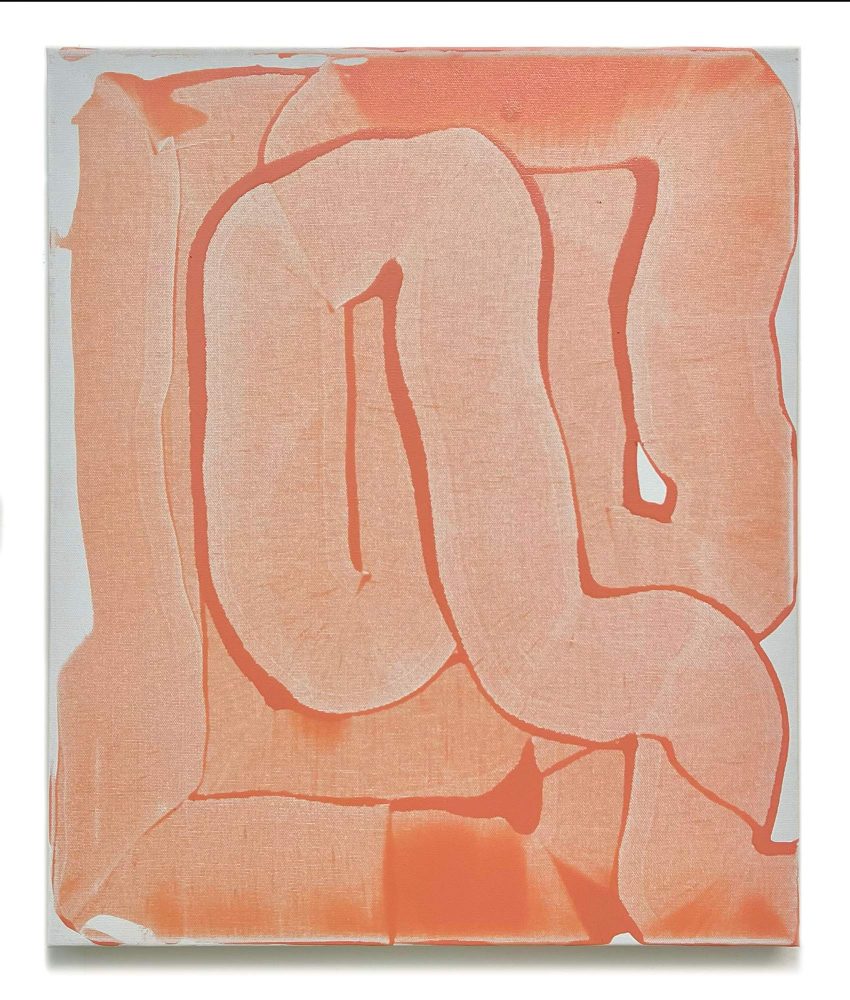

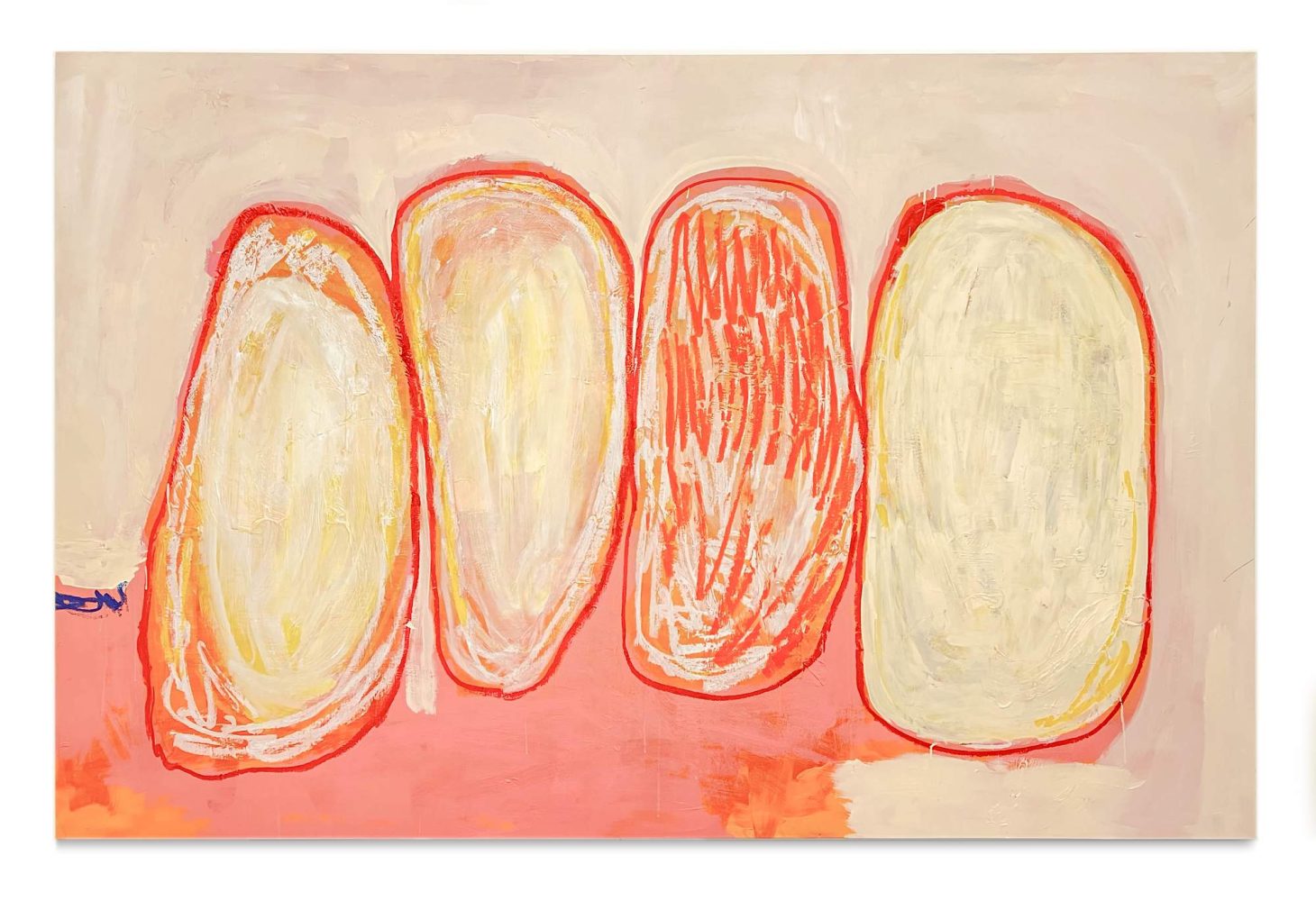

Guilt: Just Be Happy

2023

Acrylic on canvas

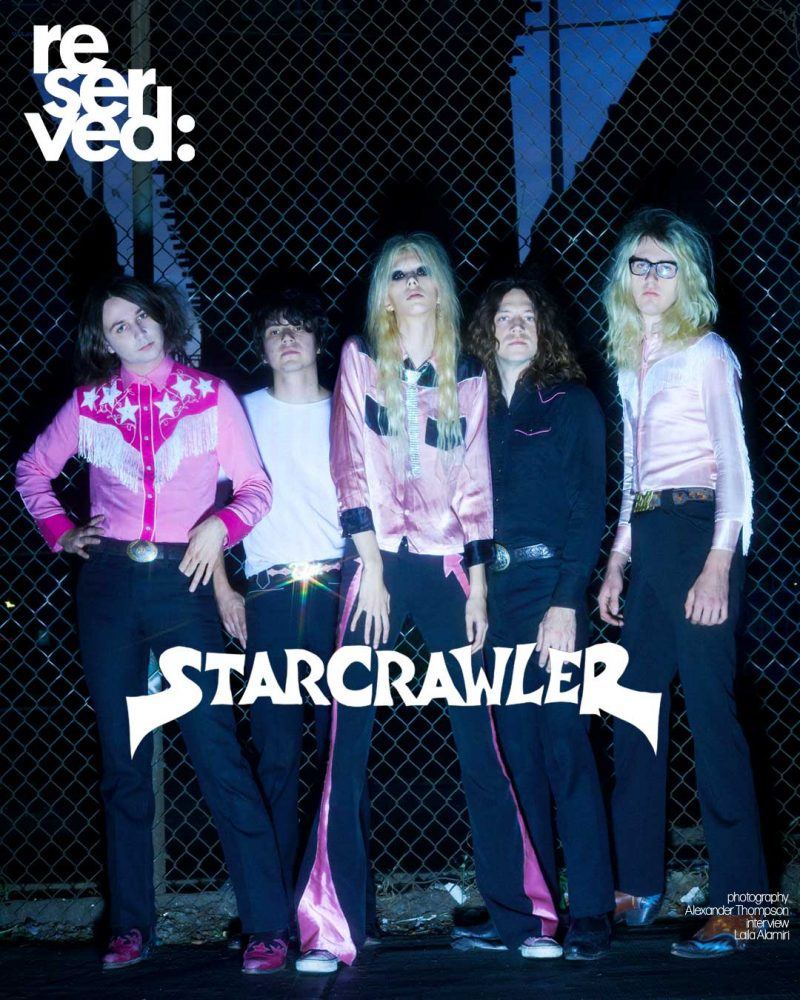

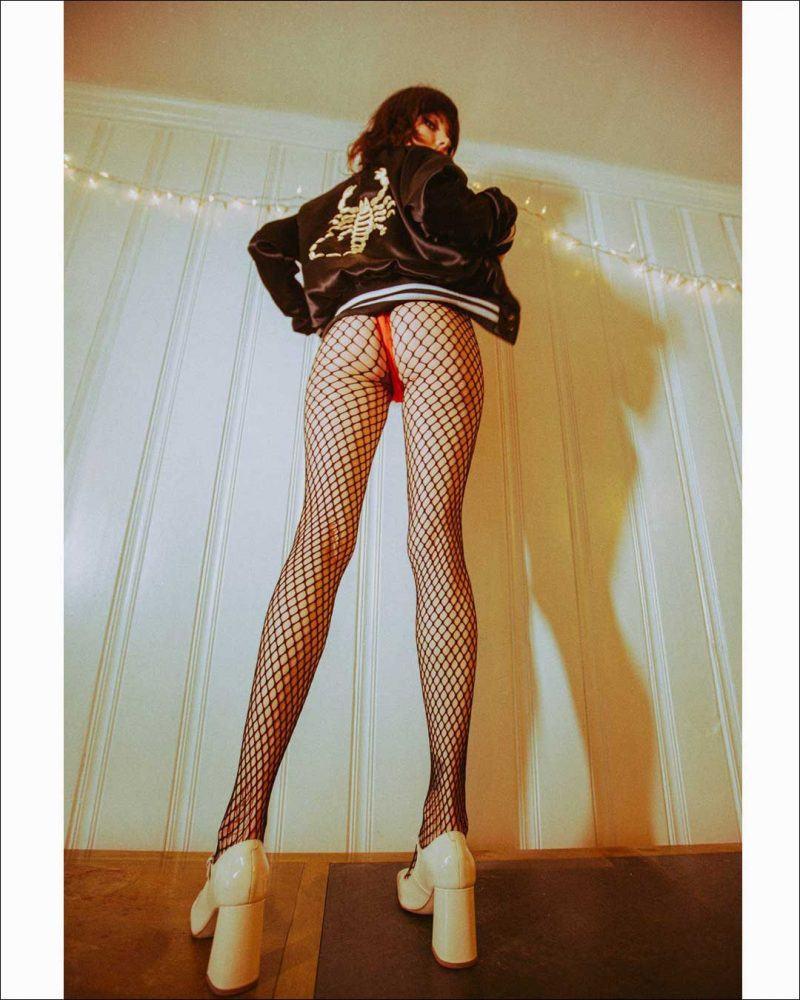

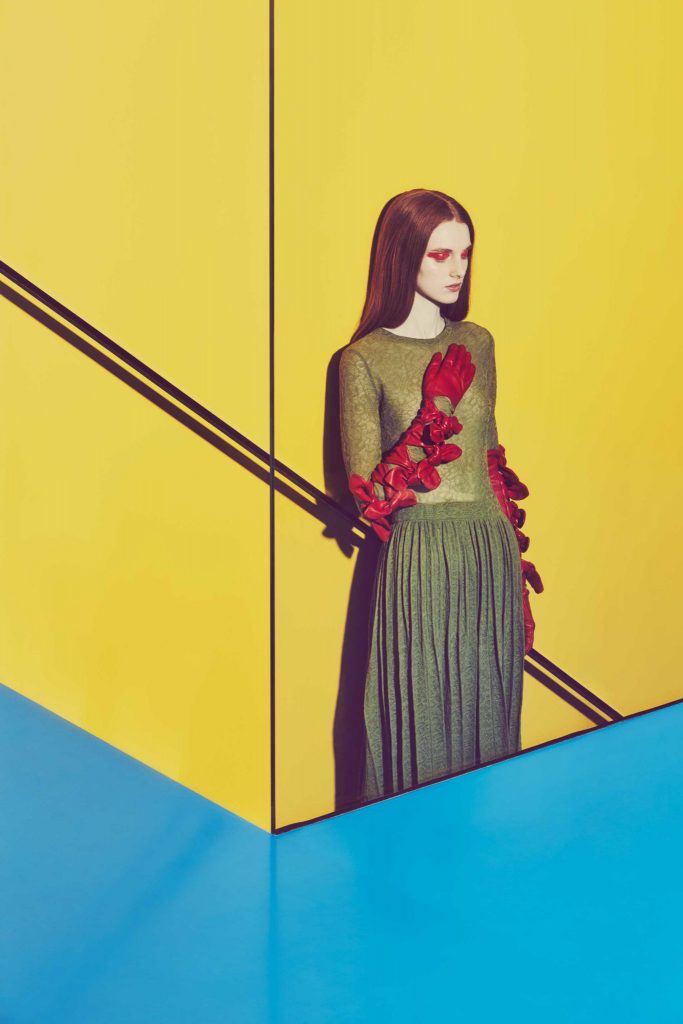

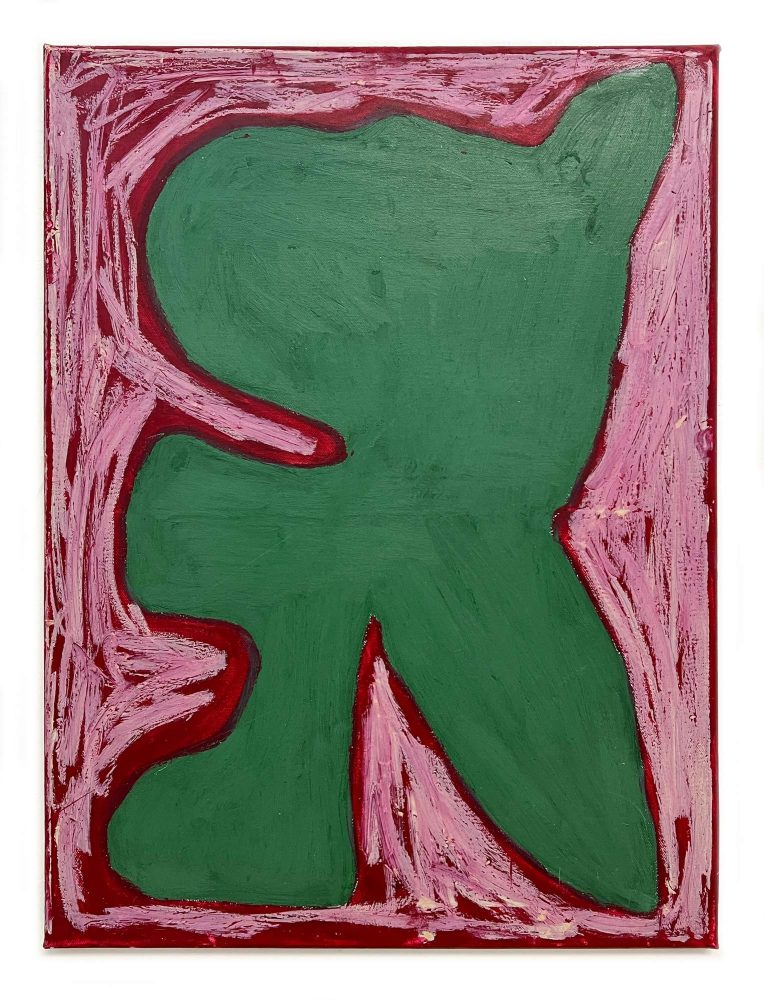

Alexandria Hilfiger

Pressure: In Harmony

2024

Acrylic on canvas

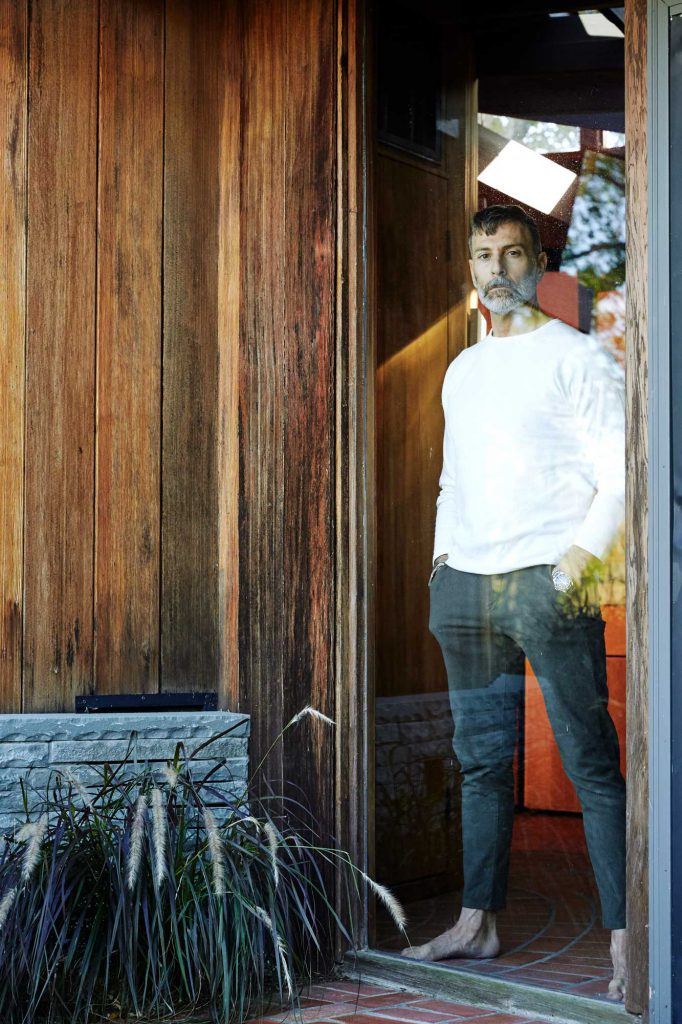

When I answer Ally Hilfiger’s Monday morning call, she’s watching the solar eclipse with her daughter and husband outside their LA home.

“My daughter is freaking out, so excited. I’m watching this like, ‘This would make a really cool art piece.’” The historic event resonates with the visionary, whose personal tribulations have colored her arc as a creator in all respects of the word. “Looking through life as an artist makes everything much more interesting,” Hilfiger muses.

While her upbringing was far from typical, it’s not Hilfiger’s pedigree which distinguishes her from peers and predecessors; Hilfiger’s decades-long battle with Lyme disease has braced her against the harsh realities of this mortal existence, while prodding her to enjoy the beauty so naturally imbued in life, if only you’re willing to glance around. Hilfiger’s adolescence in New York City, as well as her parent’s predilection for the sartorial, groomed the burgeoning artist with a keen eye and fighter’s spirit.

“I was born in New York City. Both of my parents were artists, and designers. I grew up around color and texture, caring about your environment. My mom was not only a clothing designer, but she also did amazing interiors and she cared very much about it. She took amazing risks. Interior design, along with fashion, was always a massive influence in my life aesthetically. In a way, aesthetics helped me get through some extraordinarily painful times in my life.

I was bitten by a tick at seven years old and became infected with Lyme disease and babesias, which is very similar to malaria. I was misdiagnosed for twelve years, so it was a great struggle. We didn’t know what was going on with me physically. I was really ill. I was a really strong kid, though, mentally. I was sensitive, very sensitive. I had a lot of ailments: sore throat, my joints were always hurting, I always had headaches, extreme fatigue. Then, it became neurological. As the years went on, hormones shifted, and I got in a bad snowboarding accident. The disease progressed and attacked every single part of my body. It was grueling. I was finally properly diagnosed when I was nineteen years old.”

Similar to her entire timeline, Hilfiger’s self-identification in the art world was unorthodox, and borne out of seeking grace amidst grit.

“At fifteen years old— in New York City, in high school— my family was there for 9/11. That was pretty intense. At the same time, that same week, my uncle who had been battling brain cancer passed away. My parents were separated. I was living with my dad in the city and I was the eldest of four kids. It was a lot to process. I had a moment when I was witnessing somebody painting on canvas and I felt that ‘This is me. That’s who I am. That’s what I need to do.’ I bought a bunch of large-scale canvases and really went for it. I painted a massive body of work, and then continued to paint throughout my life, starting at 15 years old.”

Hilfiger found refuge and renaissance through spiritual exploration, an inward odyssey that granted outward relief.

“I’m a very physical artist. I love to move when I paint. There’s a very intimate moment when you start bonding with the blank canvas. It can be a bit erotic at times, because you’re unveiling this virgin canvas and starting to pour all of this emotion and color into it. Sometimes, the canvas guides you in what it wants.

There’s not necessarily always a plan and there doesn’t have to be. That’s what I learned about life (laughs): Opening up and surrendering to the energy in life and showing up for what you need to and what you value. I had to go really deep into my spiritual practice. I studied yoga at 15 years old, with all of the things my dad and I were going through. I was always in so much pain physically. It was wild. The yoga really helped my muscles and joints heal, but it also really helped me delve deeper into meditation, chanting, and chakras. All of the new age things we talk about now, I was doing in 2001. I found that not only art, but exploring different forms of meditation was such an integral part of my life and my story, such a pillar.”

As Hilfiger regained the reins of her mental and physical health, her work evolved— and refused to cease.

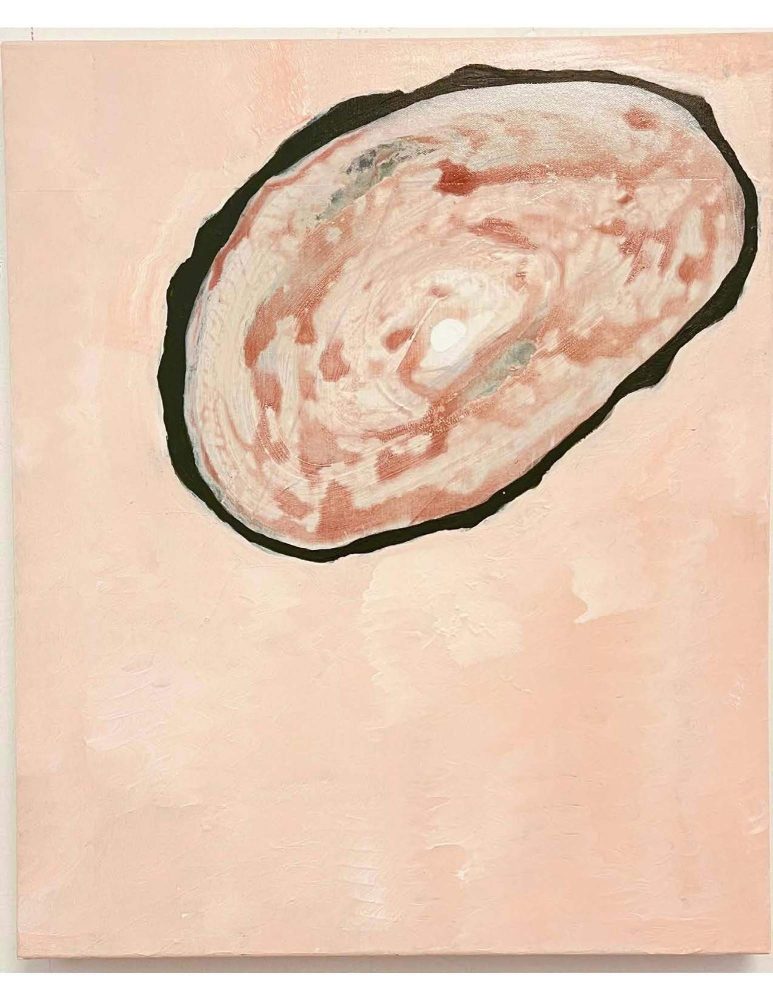

- Alexandria Hilfiger Portal in the Oyster Shell 2024 Ink and acrylic on canvas

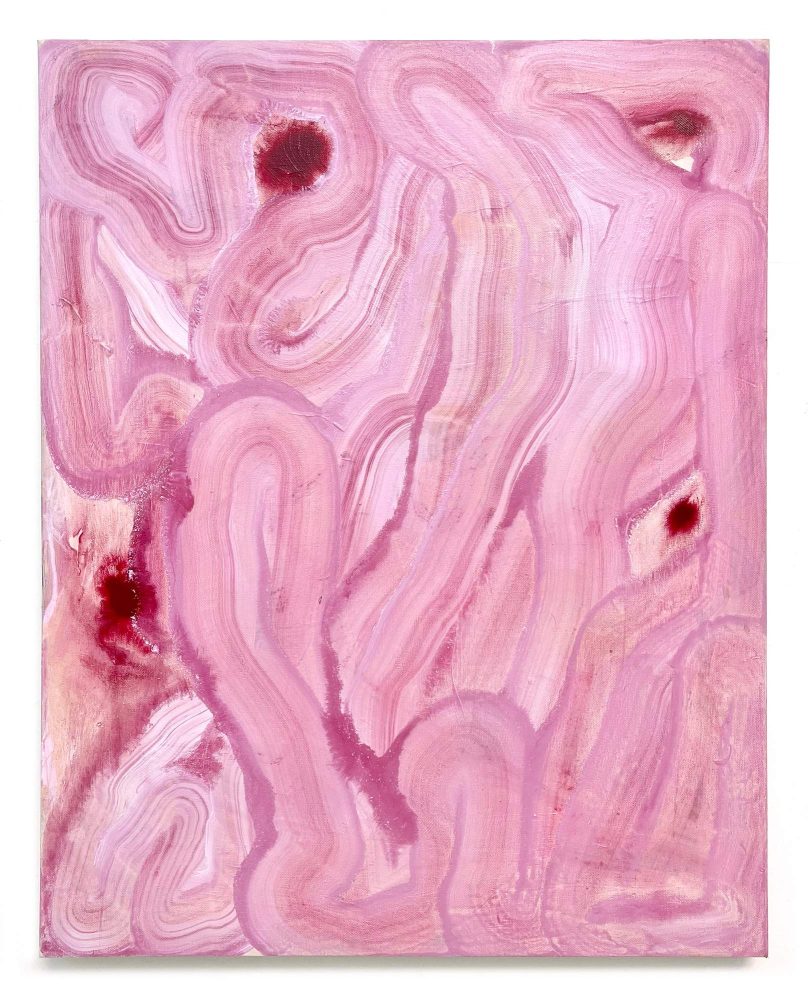

- Alexandria Hilfiger Life Lines 8 2023 Ink and acrylic on canvas

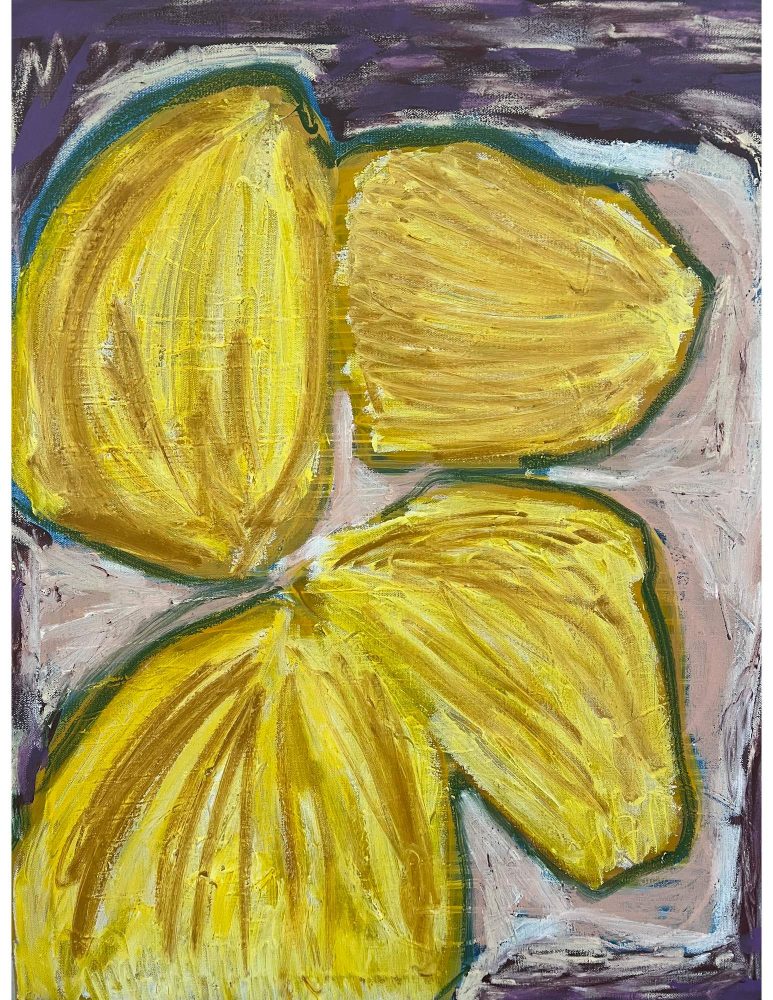

- Alexandria Hilfiger Breaking Open: Yellow Forces 2024 Oil stick on canvas

- Alexandria Hilfiger Guilt Beyond Resistance 2024 Ink, charcoal, and acrylic on canvas

“My work developed, of course, as I did. Usually, people don’t get over the type of disease I had. Gratefully and luckily, my family had resources, so I was able to go to different doctors and try new treatments. I didn’t have to work, although I always did. I always worked through it. I was styling fashion shows, styling bands. I loved fashion and styling. And, I was always painting. Lyme disease causes insomnia, so I was up at night and used my energy to paint and experiment. I was always ill. I never went to art school or anything. I taught myself and watched a lot of documentaries and other artists. I started getting into group shows in New York City in my very early twenties. The first poster of my show was me topless with globs of paint on my nipples. I was being provocative. It was like my playground.

Hilfiger’s prowess extends far beyond the canvas, delving into the familiar nooks of her family business. Though, as her course was once again rerouted, Hilfiger rediscovered her paint brush.

“For three years I had my clothing line, NAHM. In that time, I got really, really sick and had an aneurysm. I had to close the company. I felt like I had let everybody down— the people who worked for me, my family. I was so depressed. I moved down to the Caribbean and painted for six months. I also taught art to the local school children, and did ballet and reading with the preschoolers. I taught them the freedom of dance, so I would bring my scarves and my sarongs and we would just fly around, dancing and interacting with each other and the colors. It was showing children the power of color and movement.”

As Hilfiger located the power within herself to heal her chronic ailments, she also allowed herself the embrace of the universal, divine tonic: love.

“I met [my husband] Steve right after I opened my clothing company in New York. He was with me through the Lyme relapse. Of course, when you’re only a year and a half into a relationship, you think, ‘Why is this person going to stay with me? I’m so sick.’ It’s so cheesy, but it’s so true in my experience, because I’ve witnessed it not only with myself, but with several other family members who went through health crises: love is the biggest healer. When you start to give up on yourself, you think, ‘What kind of a life is this? What is the point?’ It’s not sustainable. I started to feel unworthy. He stayed, and we fell deeper and deeper in love. We moved to California together and got pregnant. It was such a miracle for me. I’d always wanted to be a mom, but I never even thought my body was capable of doing it, because I was so sick.”

The marvel of Hilfiger’s life— both her own and her daughters— was a story too valuable to keep to oneself. In an effort to jump two feet into Lyme disease activism and give back to the world about which she’d so thoroughly educated herself, the executive producer of The Quiet Epidemic penned her plot.

“I worked so hard to get better. I was totally sober. I did all the diets. I was a very good patient, and I think it worked. During that time, I thought, ‘I need to write my story for other people who are sick with Lyme disease.’ I want to be able to share what worked for me with other people. If I had any sort of roadmap, maybe I would have done it three years earlier. I focused my pregnancy on writing my book, had Harley, sold the book, and went on a book tour her first year. She came with me.”

Given the success of Hilfiger’s memoir, Bite Me: How Lyme Disease Stole My Childhood, Made Me Crazy, and Almost Killed Me, her Lyme activism admirably consumed her waking hours, shadowing her inherent passion.

“I kind of forgot that I was a painter. I went so deeply into Lyme advocacy and motherhood that I forgot that it was crucial for me to paint. Right before COVID, I was starting to have a lot of anxiety and was more emotional than usual. I was not myself. Everything was so overwhelming and scrambled. All I knew how to do was paint. When family members were talking at me and we were trying to figure out what to do, I’d paint single lines on the page in ink. I didn’t even have a studio set up. I had a little desk in a playroom and I had all of my art supplies hidden in weird places. I started making these lines until I had hundreds, and hundreds, and hundreds. I realized that every single line represented one day. Every little undulation in the line, or imperfection, or hiccup, was all of these parts of your day that you’re experiencing in your mind. As difficult or painful as going through that day may be— or, it may be beautiful— putting them all together is the most beautiful. Because, yes, they’re gorgeous individually. But, putting them all together and looking at your life through that perspective, you think, ‘Wow. That was really worth that bump, because look at how gorgeous it is.’ Those are my life lines. That’s what got me back on the horse.”

Once the cap was reopened on Hilfiger’s creativity, the spigot was nearly impossible to stop, feeding her psyche at a time when the world most needed it.

“We ended up moving out to Palm Springs during COVID, and that opened me up creatively. I started making music. I always sang. I used to record on people’s albums in my teens. The art dealer that I had in New York came, saw my paintings, and started selling them. But, at the same time, I was recording music and thinking maybe I really wanted to go down this road of using my voice. When I performed, though, I had so many nerves that I realized I couldn’t do that sustainably. Instead, I come out with a song a year now. There’s a song that came out called ‘Kiss in my Direction’ that I was featured on. I’m proud of it. My tits are on the cover of that one, too. It’s all full circle! No pun intended.”

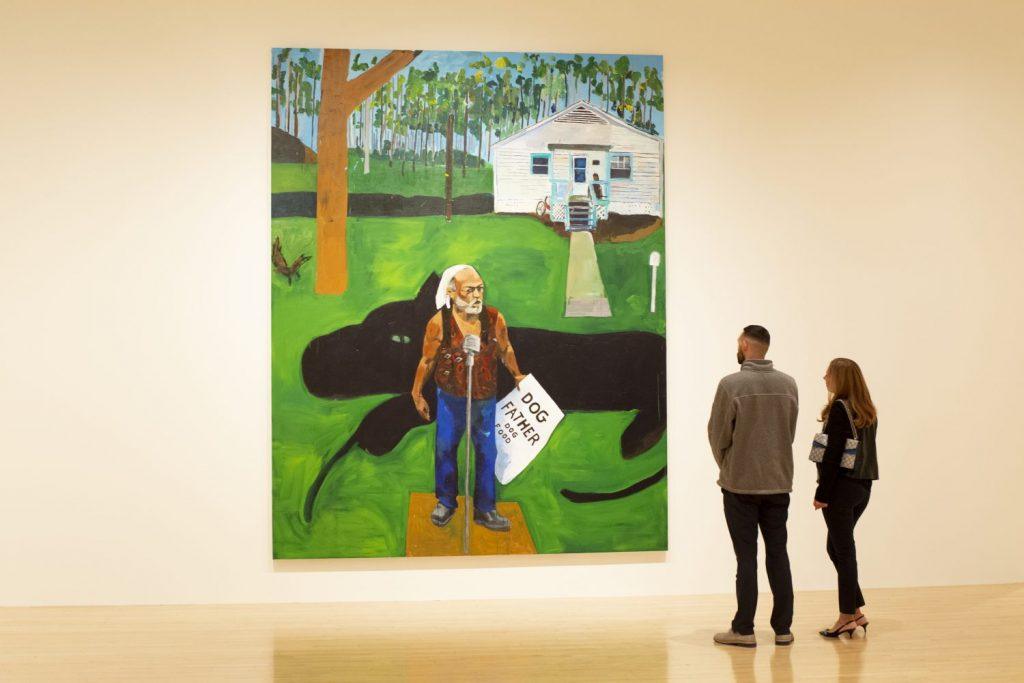

Hilfiger’s latest gargantuan venture is a solo show at Santa Monica’s swanky (and inarguably iconic) Georgian Hotel. The exhibition feels as if it’s a homecoming to the town in which Hilfiger was able to make her home, to make her family. The overdue recognition thanking her for her incalculable contributions to the community, welcoming her back into the fold with extended arms and asking her to stay awhile. As Hilfiger’s work is so intertwined with her inner monologue, the show speaks volumes to Hilfiger’s fascinations and fixations, cultivating an empathy for individuals who have tread in her shoes, particularly as a working mother.

“For this whole show, I was really focused on the beauty of imperfection, the wabi-sabi. Japan is very important to me. Harley was conceived in Japan, I lived in my mom’s womb during her whole pregnancy in Japan. I have very strong connections there. After writing about the beauty of imperfection and why it’s important to start accepting all sides of ourselves— in the difficult, in the ugly, in the challenge. That’s what nature is.

Overall, I’ve always been very interested in the transformation we go through when we’re dealing with guilt, particularly as women and as mothers— taking up space, being a woman who is overcoming the guilty feelings associated with being an artist and taking time away from my family and friends. Even though it’s completely necessary and crucial, it can feel indulgent. Dealing with that, and then moving into giving ourselves permission to let go of that guilt and start to accept who you are. Who I am as an artist, and as a mother, and as a person means that I might not feel amazing every day because I dealt with crazy Lyme disease for 27 years, accepting that I might need to sleep for two hours longer than most people.

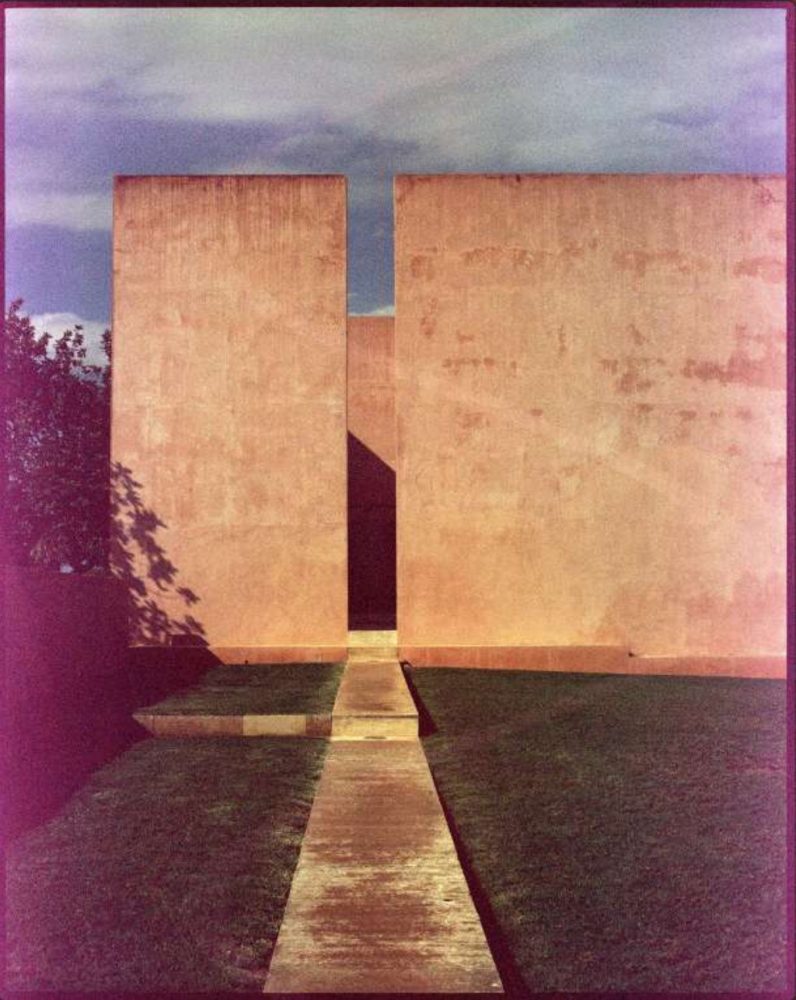

- Alexandria Hilfiger Pathways III 2024 Acrylic and ink on canvas

- Alexandria Hilfiger Pathways I 2022 Acrylic on canvas

- Alexandria Hilfiger Pathways II 2022 Acrylic on canvas

- Alexandria Hilfiger Pressure: Pink Walls 2024 Oil and acrylic on canvas

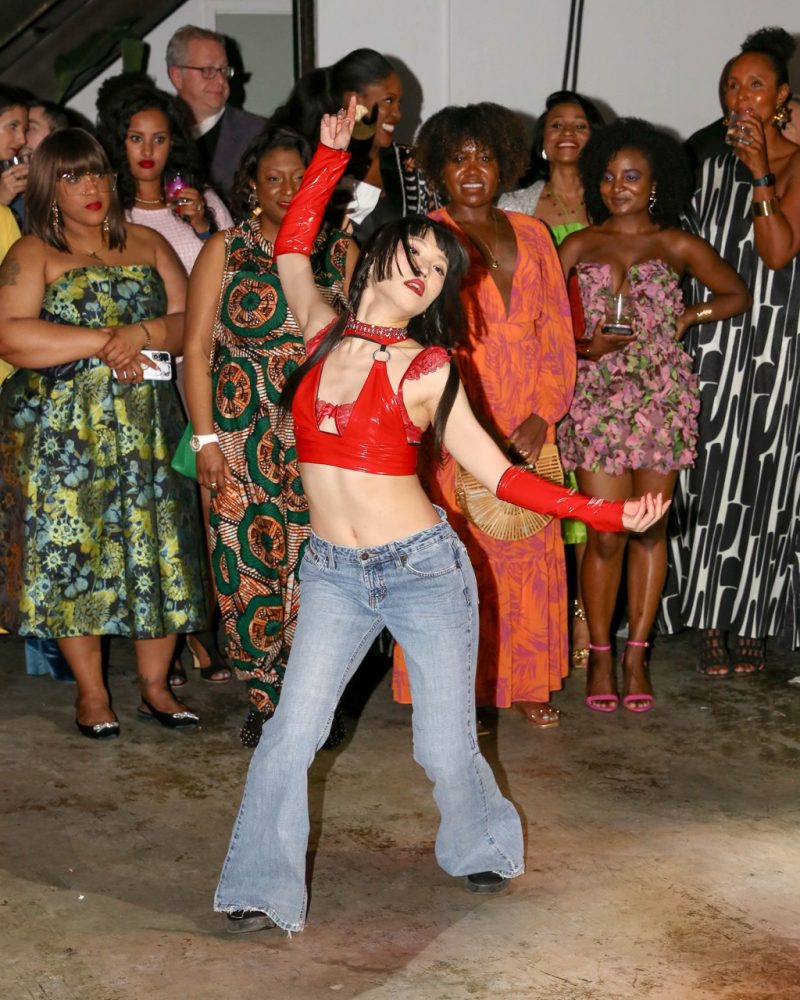

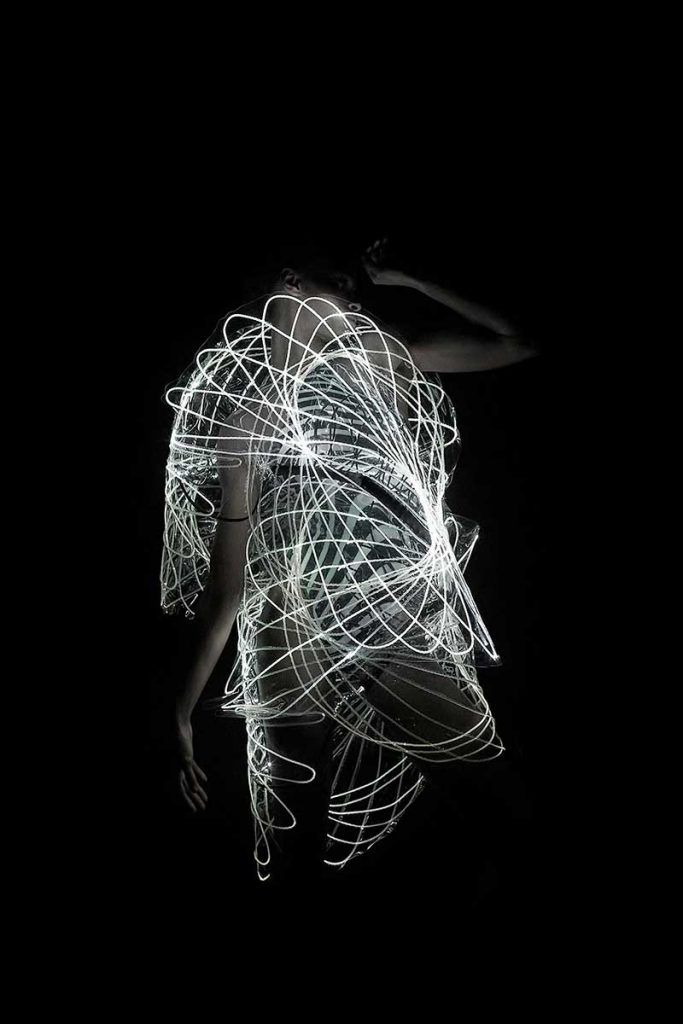

Then, there comes the point of freedom, which is my ‘Body Language’ series. It’s what I believe the soul looks like, a complete circle. But, when it reaches the point of freedom, it starts to move into beautiful shapes.

The ‘Pressure’ series comes from feeling the pressure to keep it all together, to keep making all of what I’m making into something worthwhile and important. I want to make art for the rest of my life. What I really want for that work is for it to sell, in hopes that it helps and heals people. That’s my end of day. It helps and heals me so much. All I can ask is for it to give some sort of relief to someone.”

The reciprocity of Hilfiger’s self-restoration is constantly rippling ‘round the world, seeking to serve as many communities in which she’s been entrenched as possible. Hilfiger’s personal healing is directly reflected in her art, an integral and inseparable aspect of her identity with her body of work.

“It’s who I am. I’ve also thought about having an alias, because there’s so much stigma associated with my name. ‘Nepo baby’ is a huge thing now. I read my comments sometimes and I’m like, ‘Really? Wow. Weird.’ They care this much, and they know nothing about what art really is. Or me! But, I don’t care because it’s humanity, and I’m interested in humans and what they deal with in their minds. I would have been a psychologist if I wasn’t an artist. Always, though, an activist!

I’m going down to Washington, D.C. in a week, passing my second bill through Congress. I’m speaking in front of the Senate. It’ll be my second time. I’m bringing my daughter. If you’re in a position to be able to have these experiences, it would be such a waste to not do it.”

Not only is Hilfiger’s art, activism, and authorship a gift to the public, but her intent on leaving a positive impact in her place is stirring. With the what she has already accomplished, Hilfiger has well-secured her place in history, though she has no plan to slow down soon.

“I was so sick for so long, I can’t even tell you. I did not get out of bed for one summer in my twenties. Can you imagine? It was wild. But, I’ve gotten to watch a lot of good movies! Eva Hesse, her documentary is what brought me back during the beginning of COVID. She brought me back to myself. It reminds you, keep making work. One day, what you’re doing might get someone else out of bed to do what they’re called to do.”

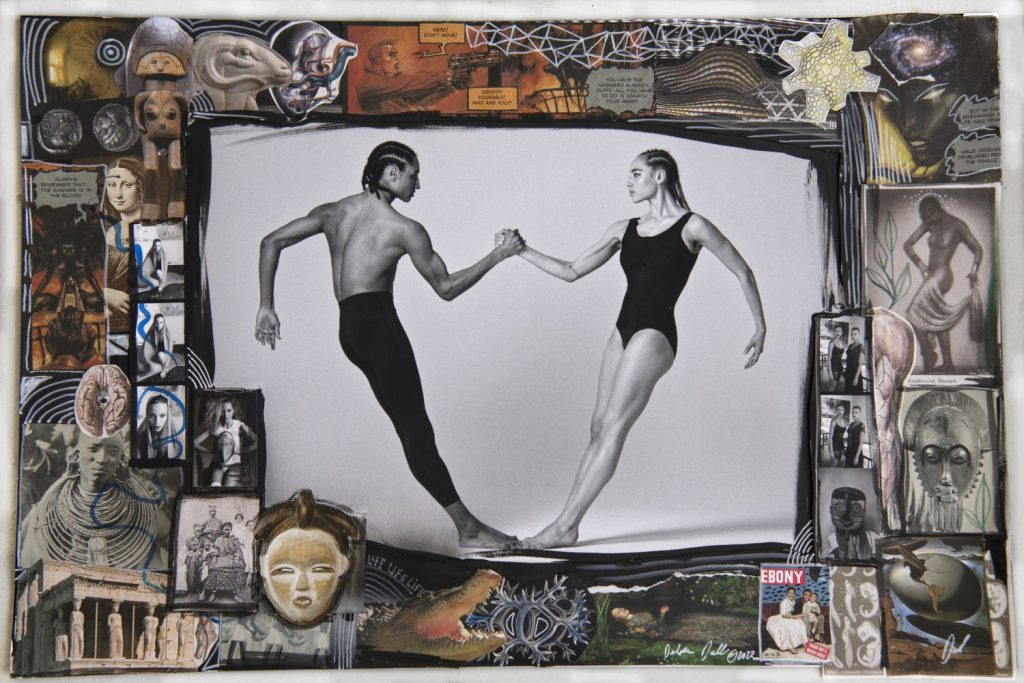

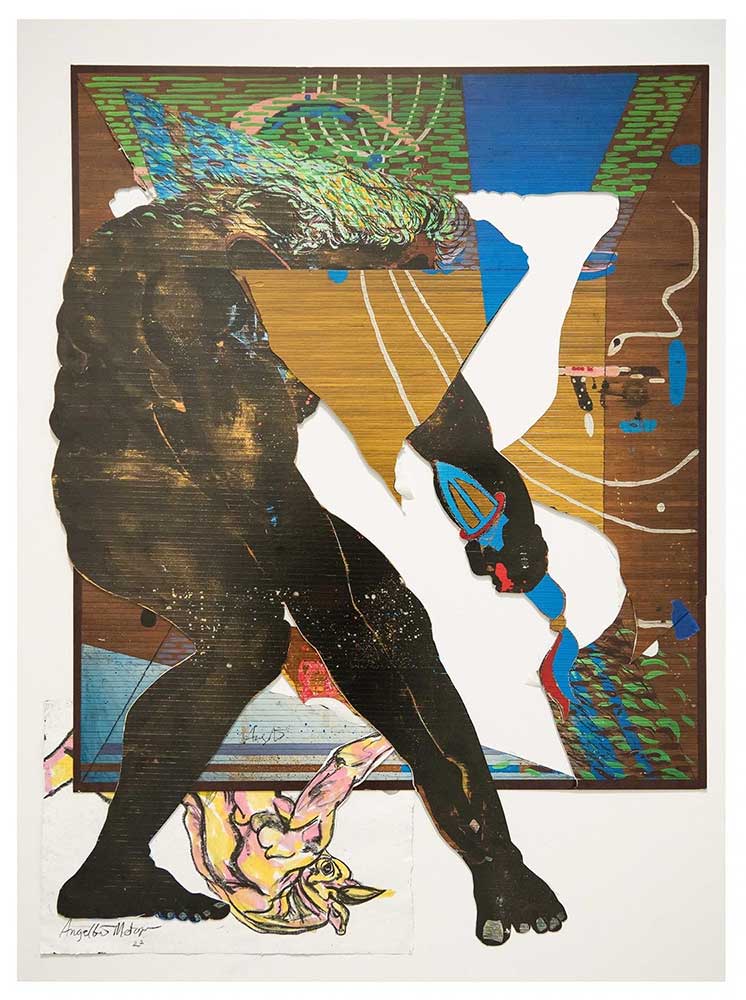

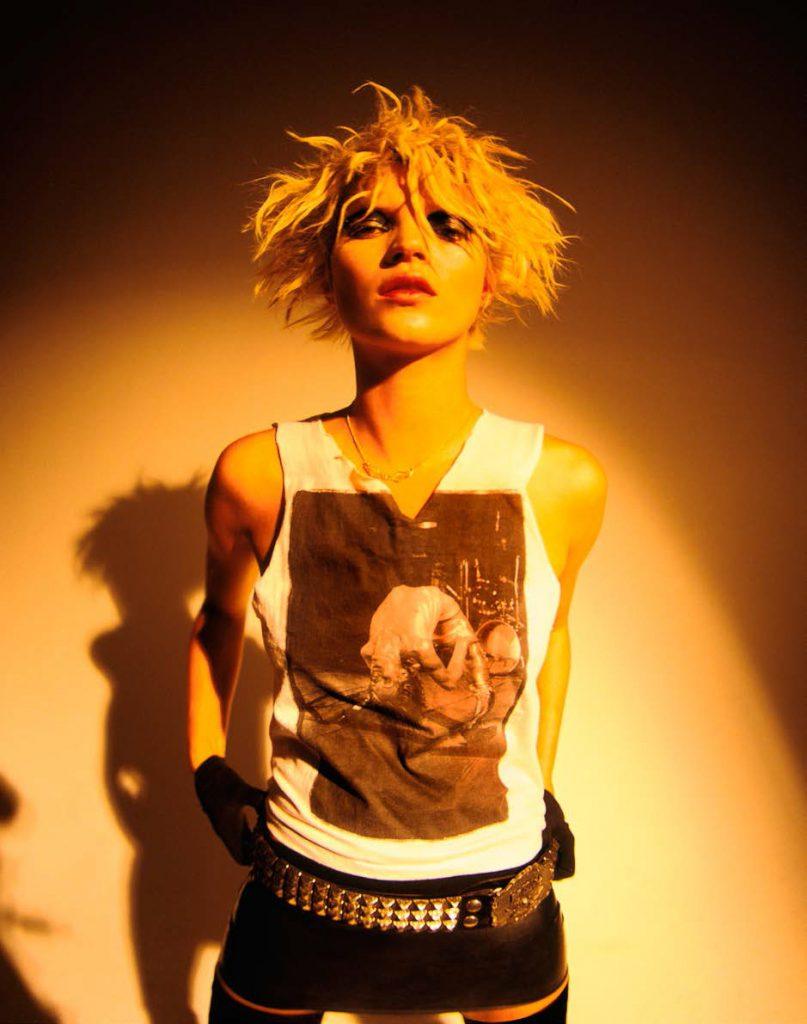

Alexandria Hilfiger

Body Language II Dancing in the Garden

2022

Oil stick on canvas