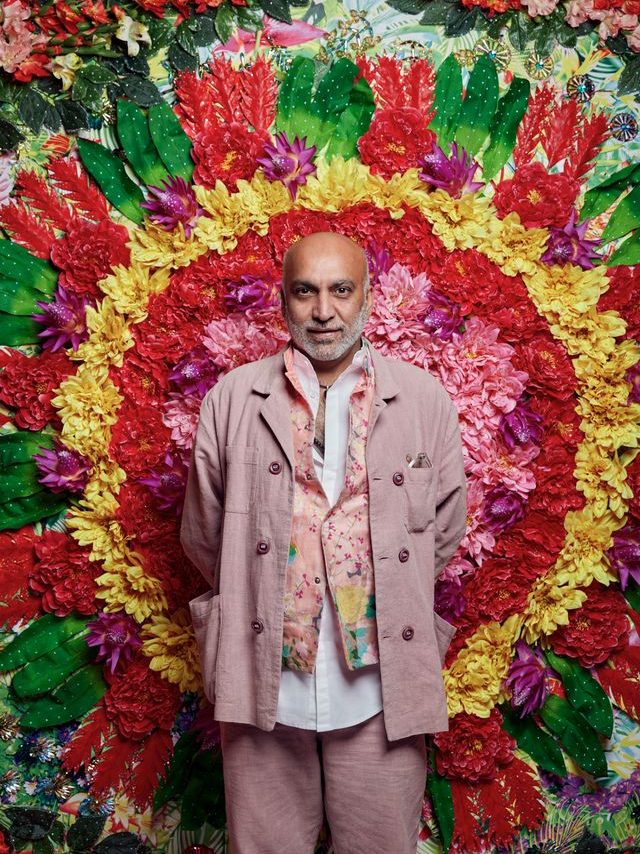

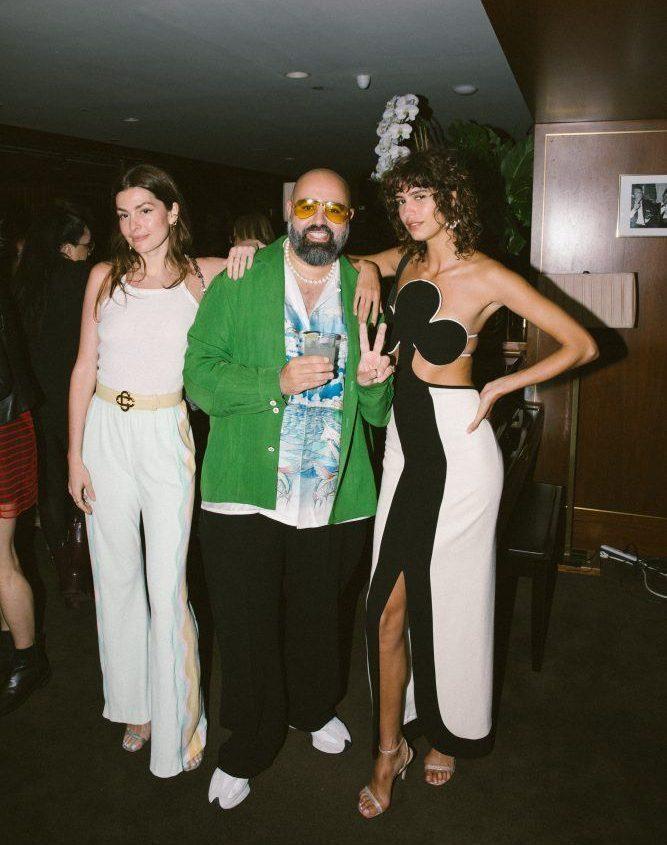

ANGELBERT METOYER

GOLDEN HORNS

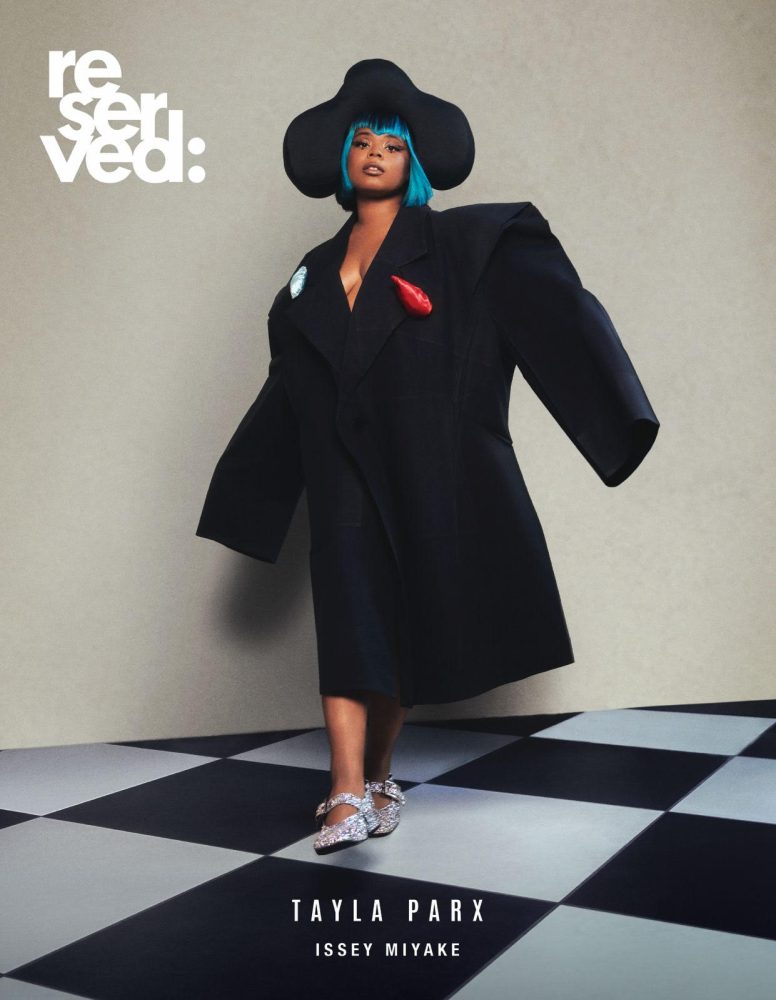

The afro-futurist artist Angebert Metoyer on metaphysics, transcendental art and shedding one’s identity in search of the divine.

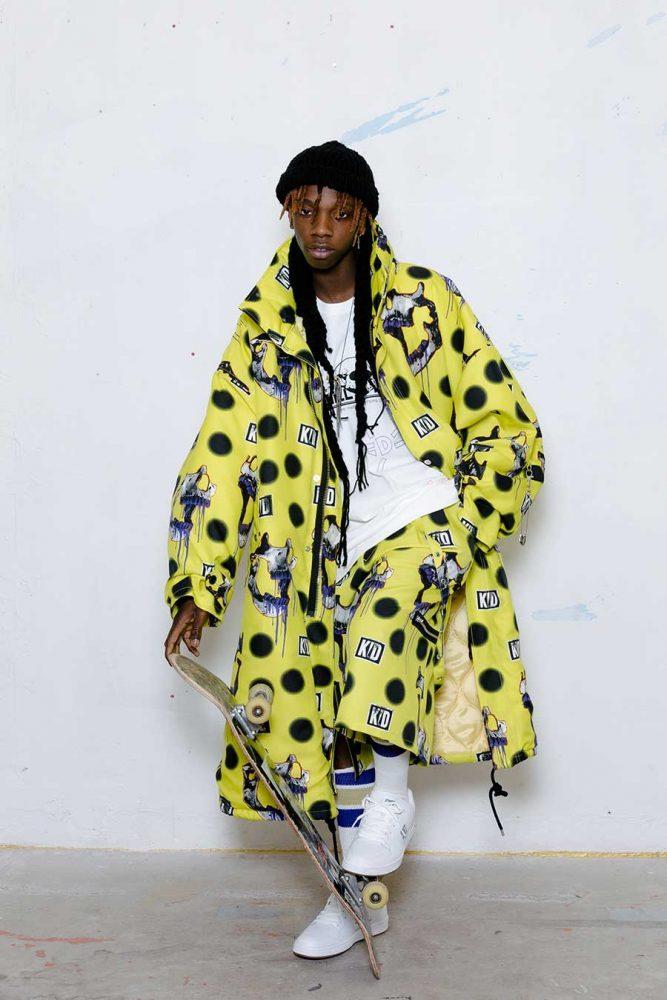

The New Orleans-born multi-disciplinary artist Angelbert Metoyer is an image-maker at the cutting-edge of afro-futurism, whose mixed-media investigations into metaphysics deep dive into trans-cultural notions of ancestral memory in order to present works that feel like cosmological star-maps of collective consciousness. His work invites the viewer into a transcendent meta-space full of anthropomorphic figures, sigil-esque mark-making and scrawled texts, where notions of past and future dissolve into an absolute present that is rendered with intense physicality in paint, spray-paint, graphite, tar, and gold dust. Metoyers’s current show at Tripoli Gallery in The Hamptons is a perfect insight into the near-shamanic art practice for which he is increasingly celebrated (his works gracing the permanent collections of various museums across the US, and the homes of some of the world’s most revered collectors of contemporary art). Entitled Golden Horns, the show explores the symbolism of the horn as a leitmotif throughout multiple cultural narratives that have had a hand in pointing the moral compass of humanity, spanning the likes of Greek mythology, Christianity and Nordic folk tales. Here, the artist speaks candidly to Reserved about reaching for something beyond the confines of his own identity in his art practice, and stepping outside of time to connect with a sense of the eternal.

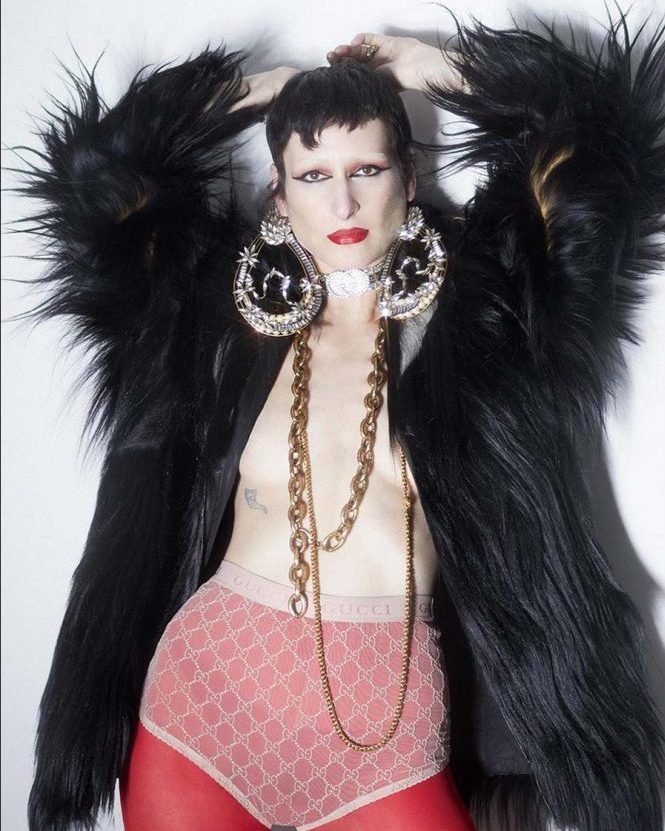

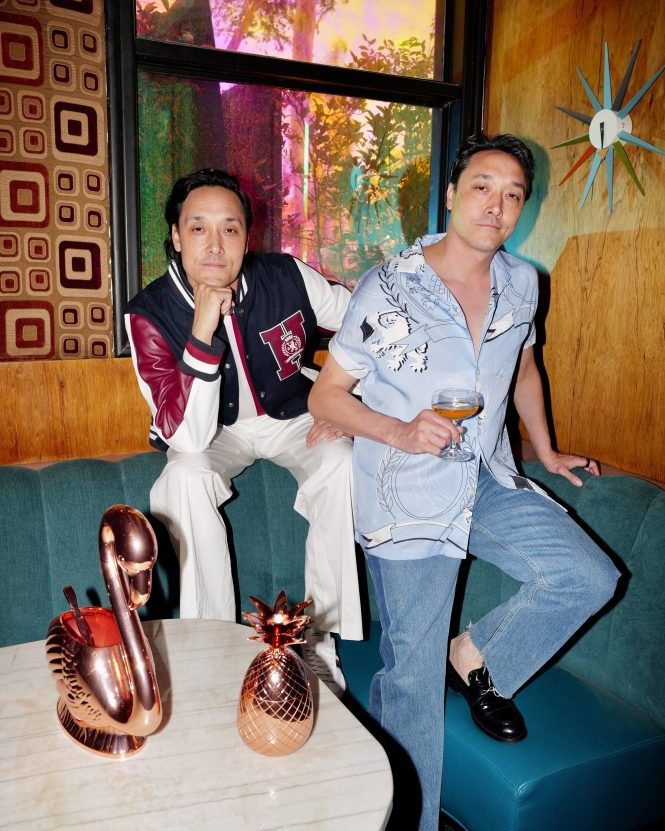

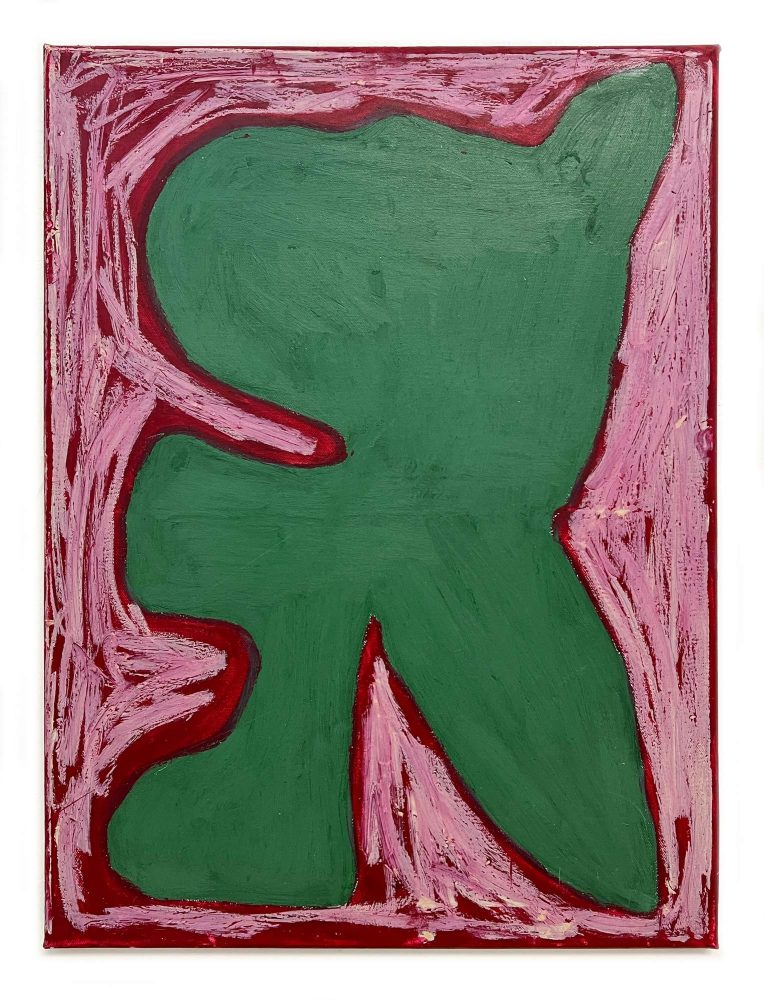

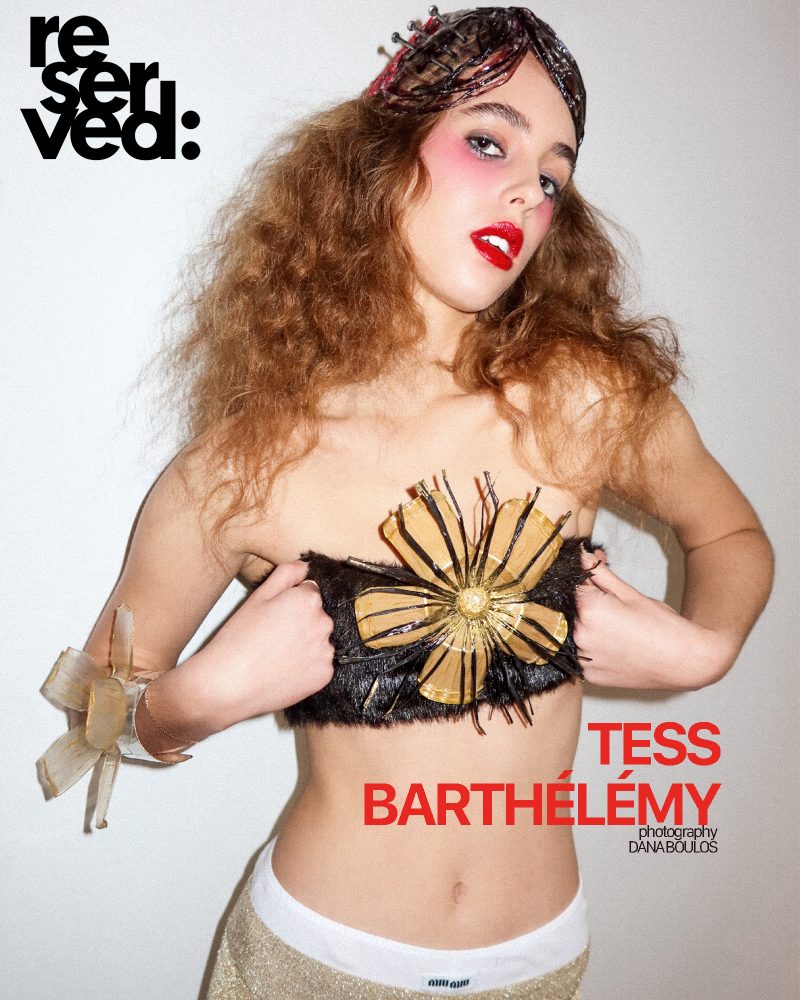

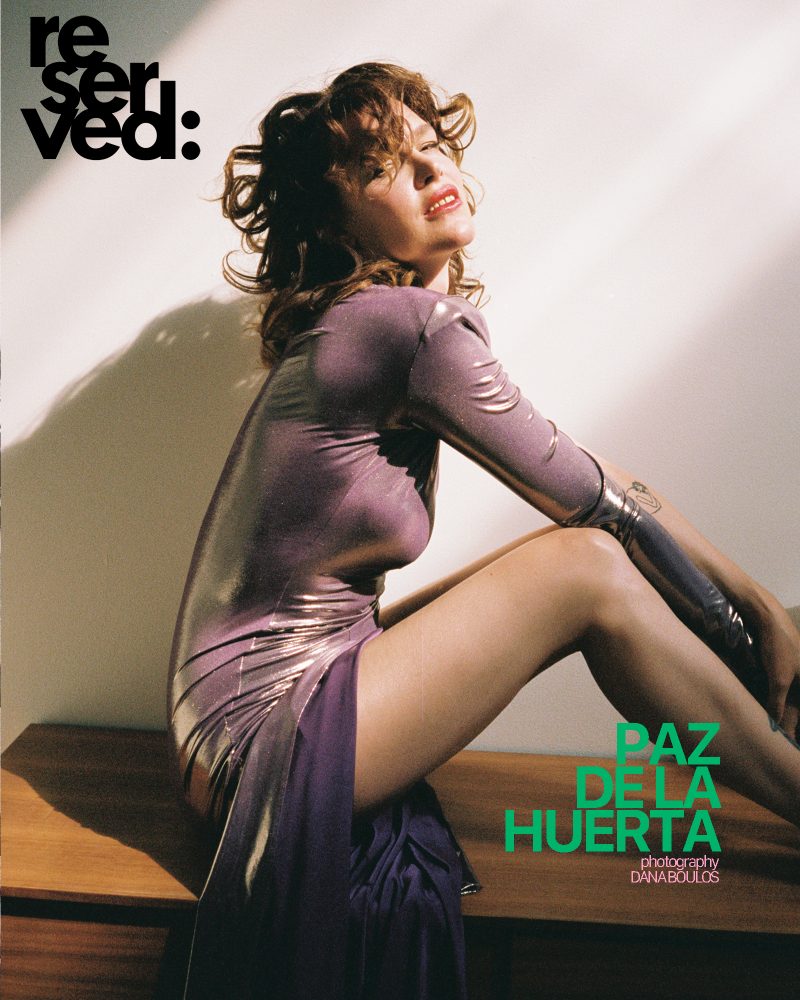

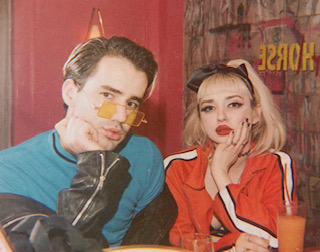

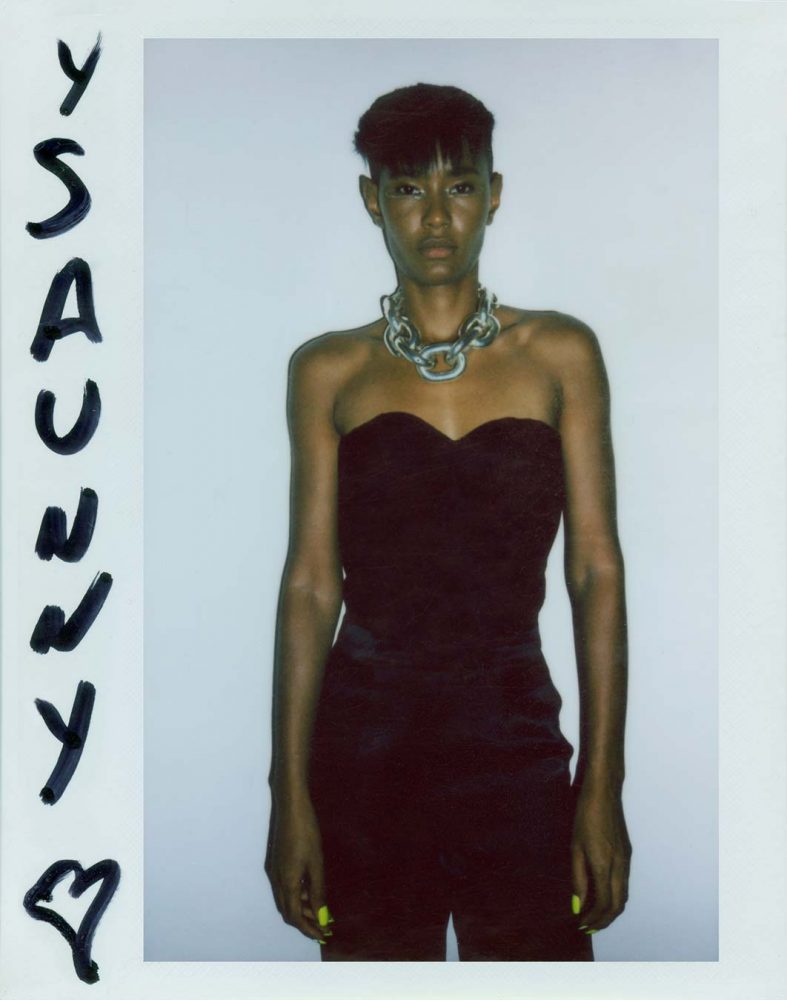

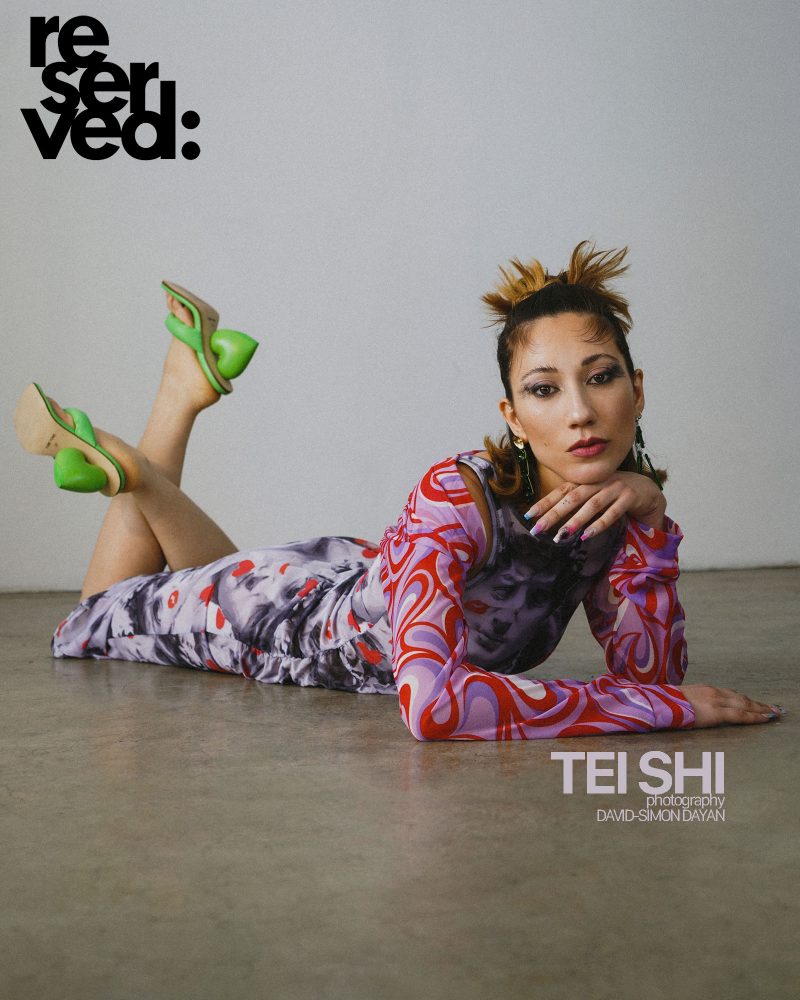

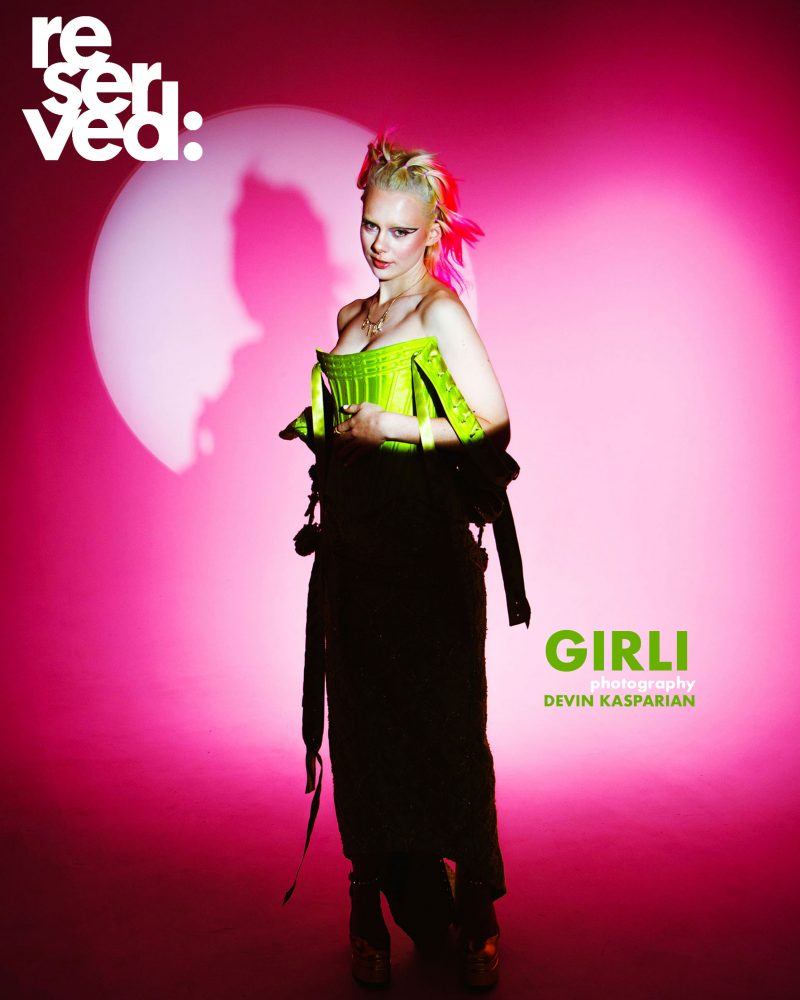

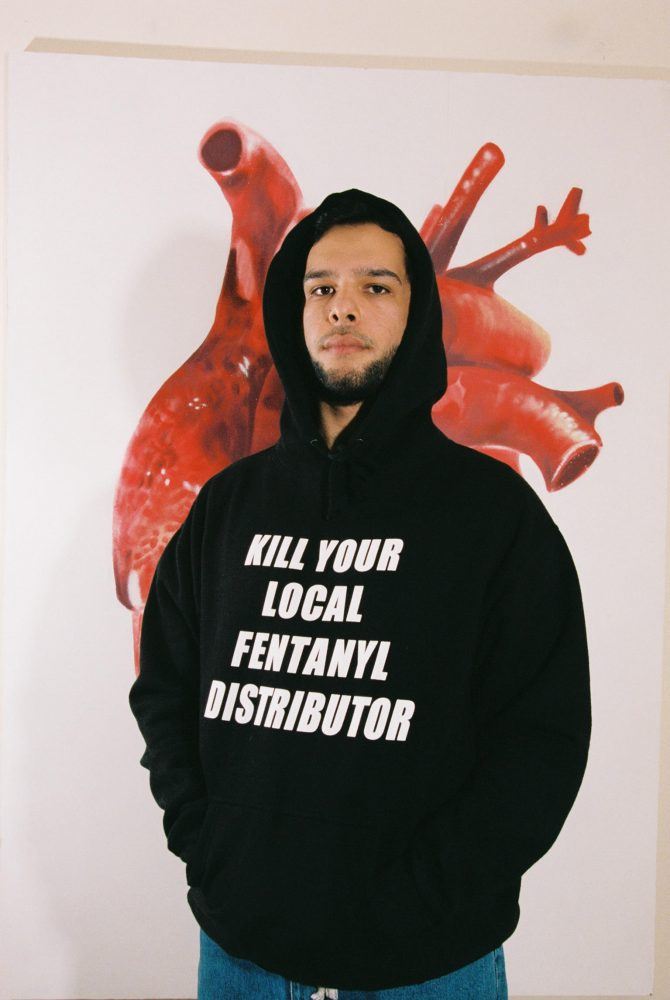

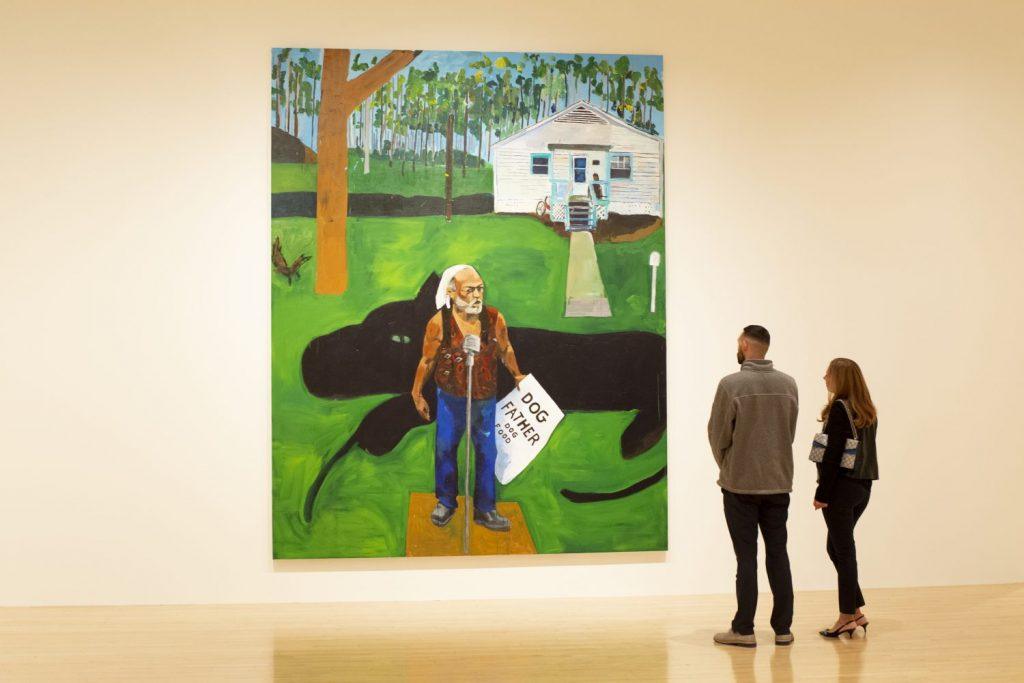

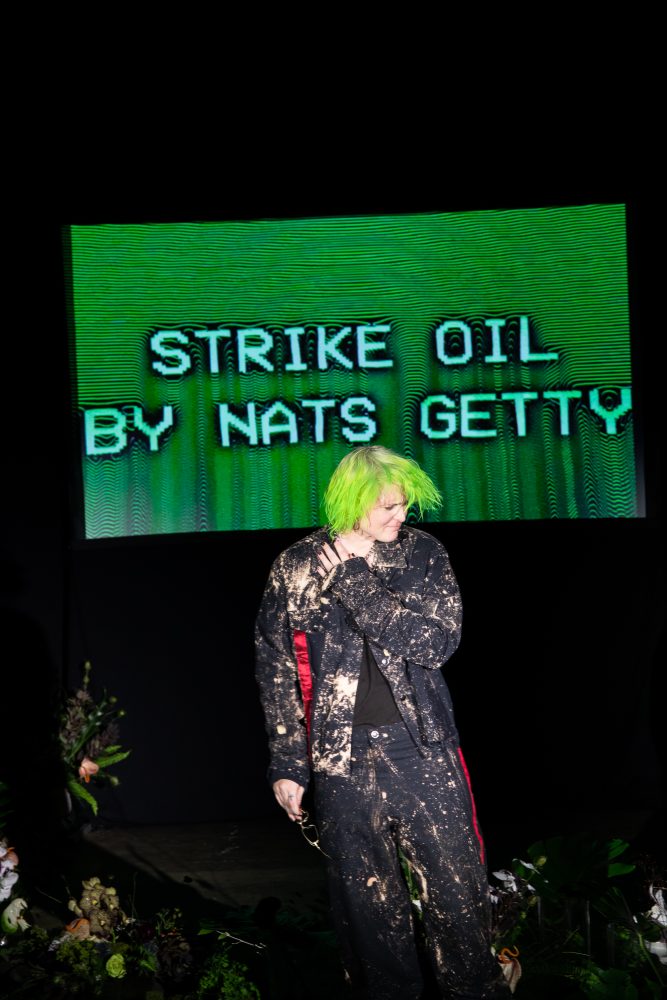

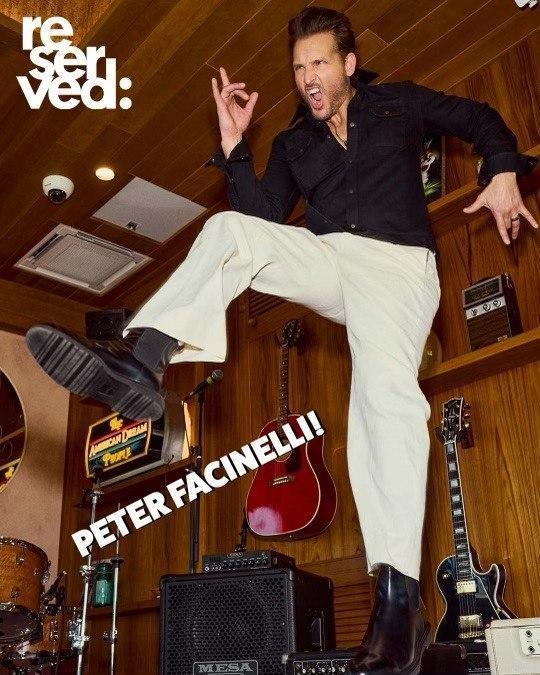

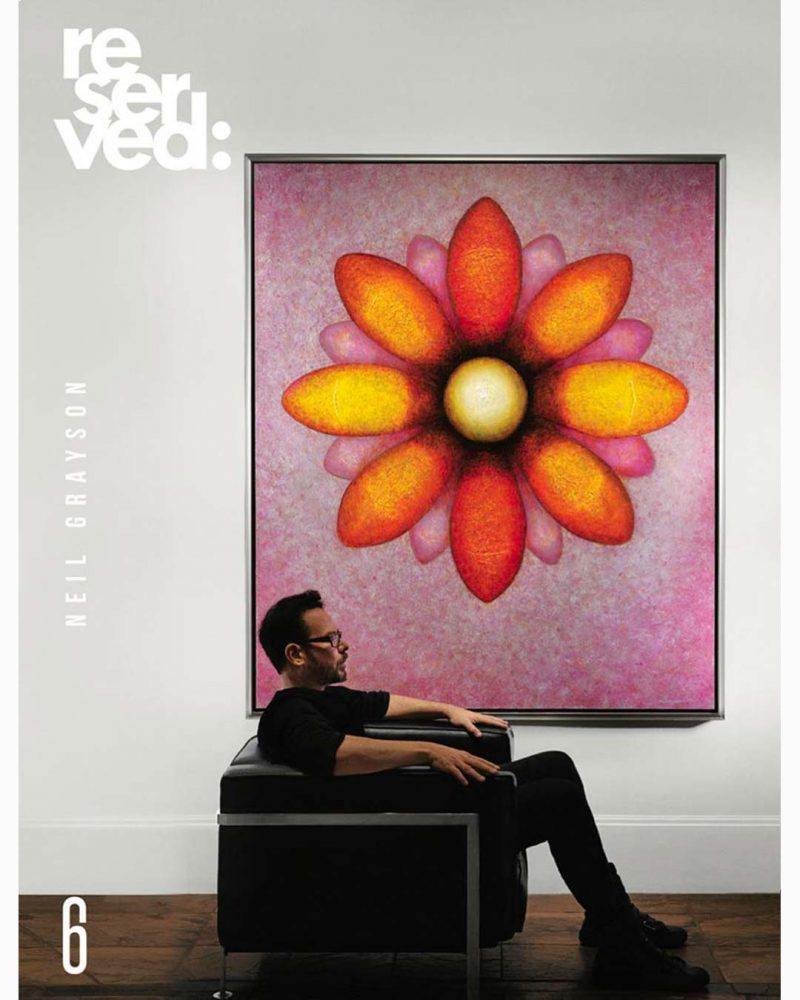

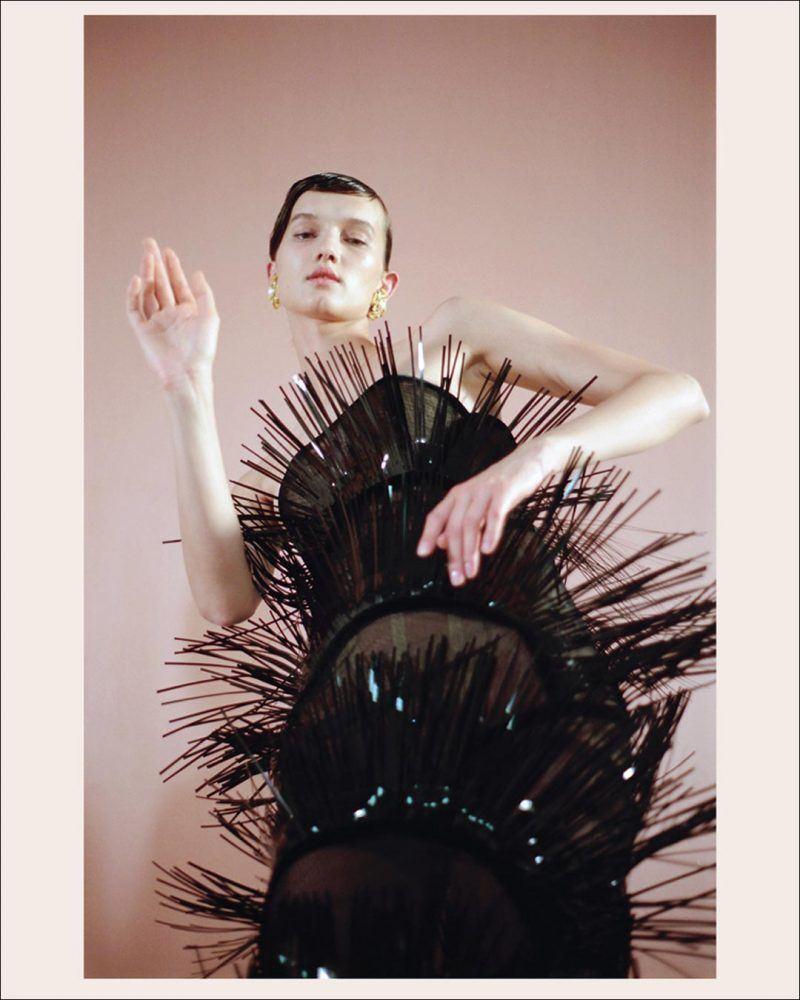

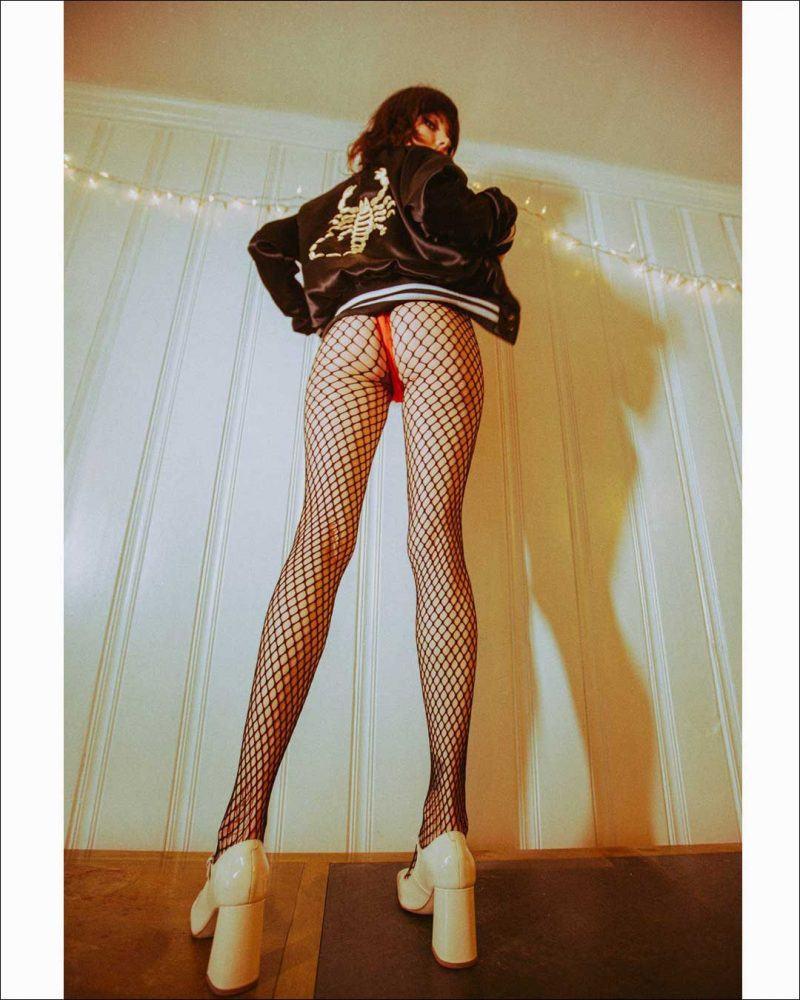

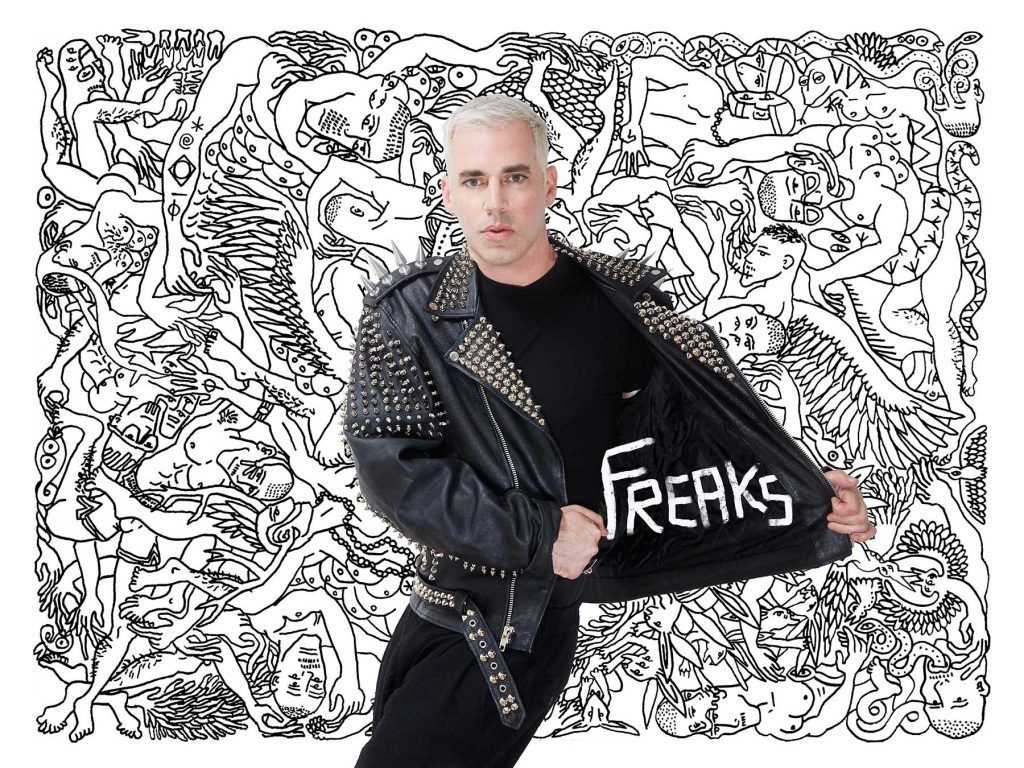

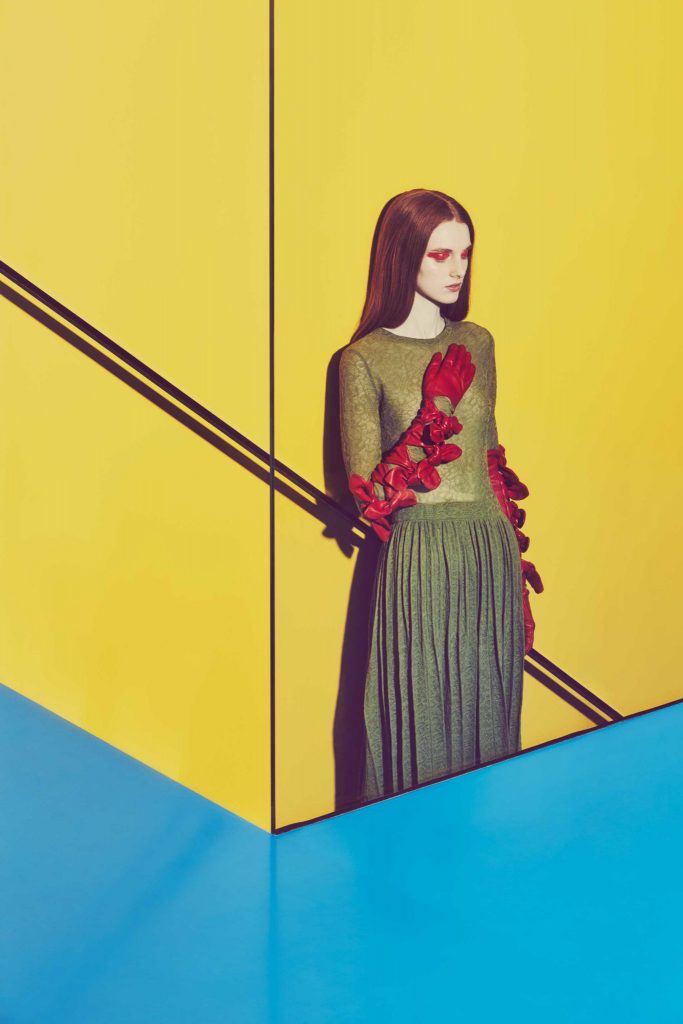

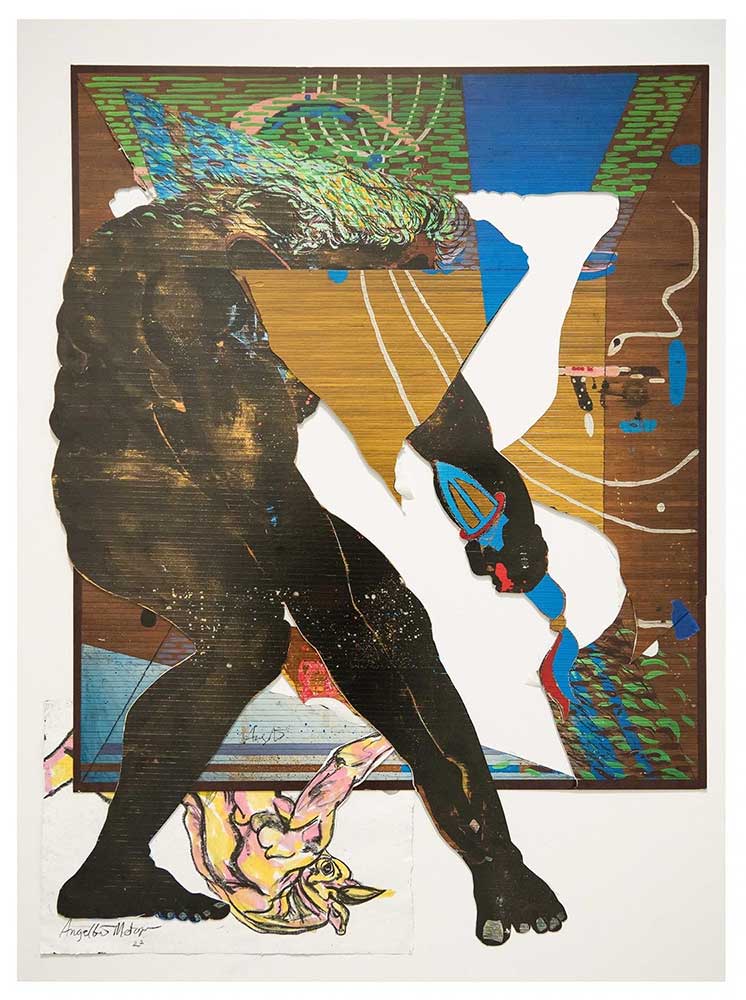

Cut No One Out by artist Angelbert Metoyer.

How does your work take shape and where do you think your creative drive stems from? As early as I can remember, painting and drawing has been about exploring my own cosmology and religion. I could probably form a more academic kind of way of thinking about it, but for me the work was always kind of about reaching this moment where all of a sudden it would be as if time didn’t exist, and I could kind of infinitely go. Those have always been moments where I feel like I can ask for anything. So, in that sense, I guess a painting will just kind of come to me. It’s like that thing Marina Abramovic says about practicing until you get a vision to make something specific. I have realized over the years that that’s exactly what I do. I have a practice, and occasionally there are moments when it’s like everything has lined up and there’s no possibility of a mistake, because even the mistakes fall into place. At those times, I’ll see something totally specific, and there is no practice involved. It’s like a vision, and I just follow through with it.

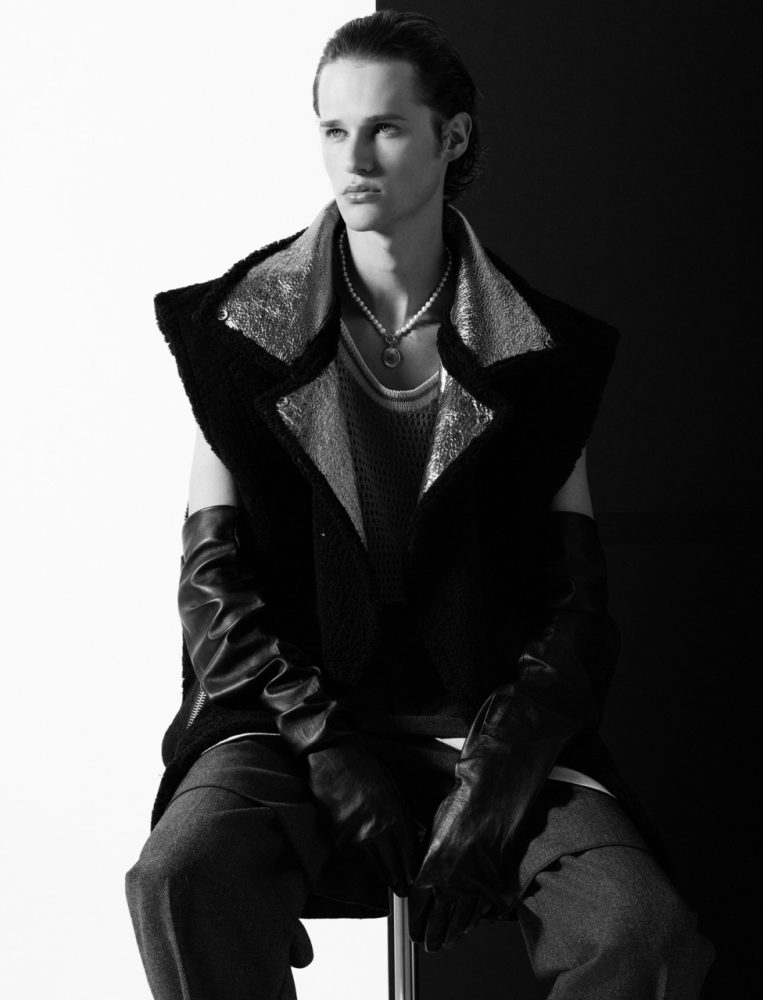

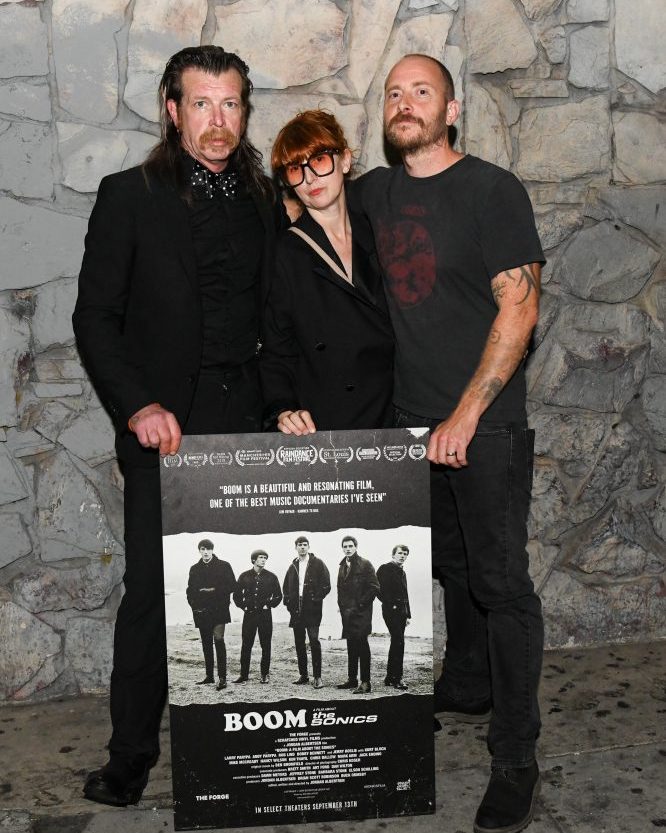

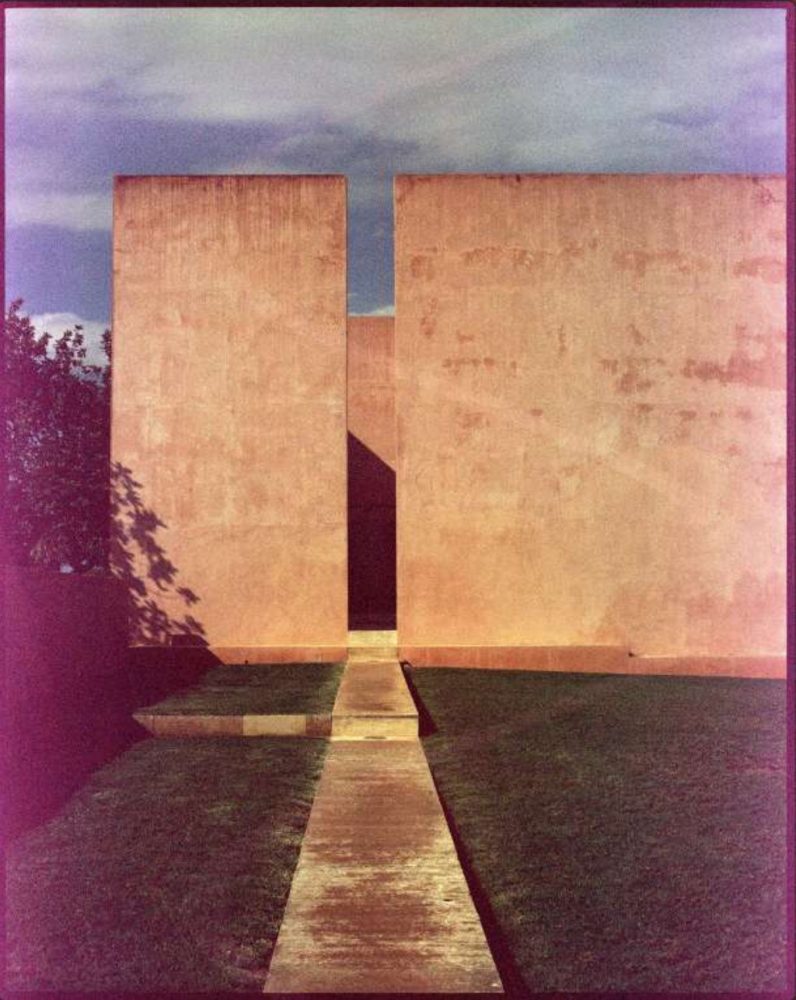

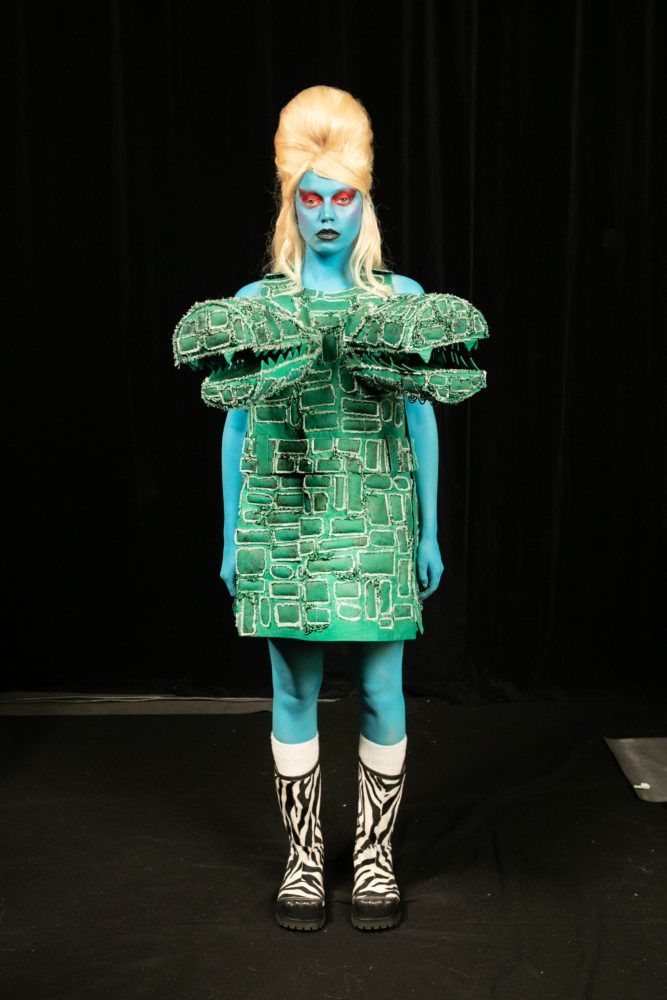

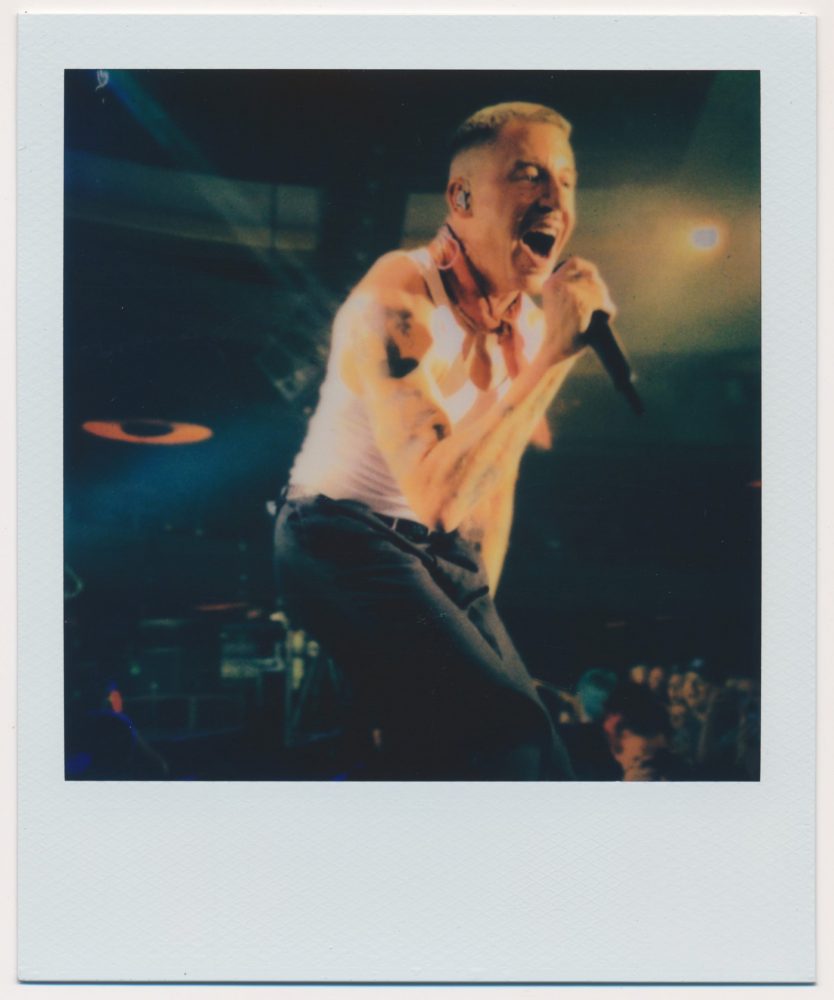

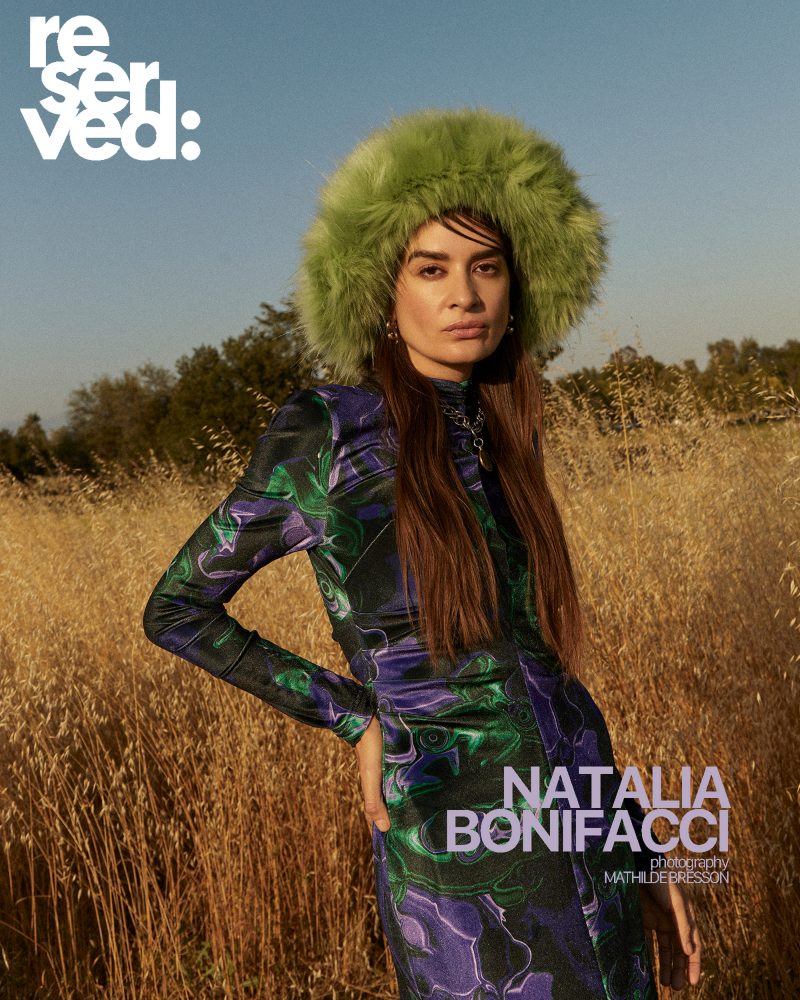

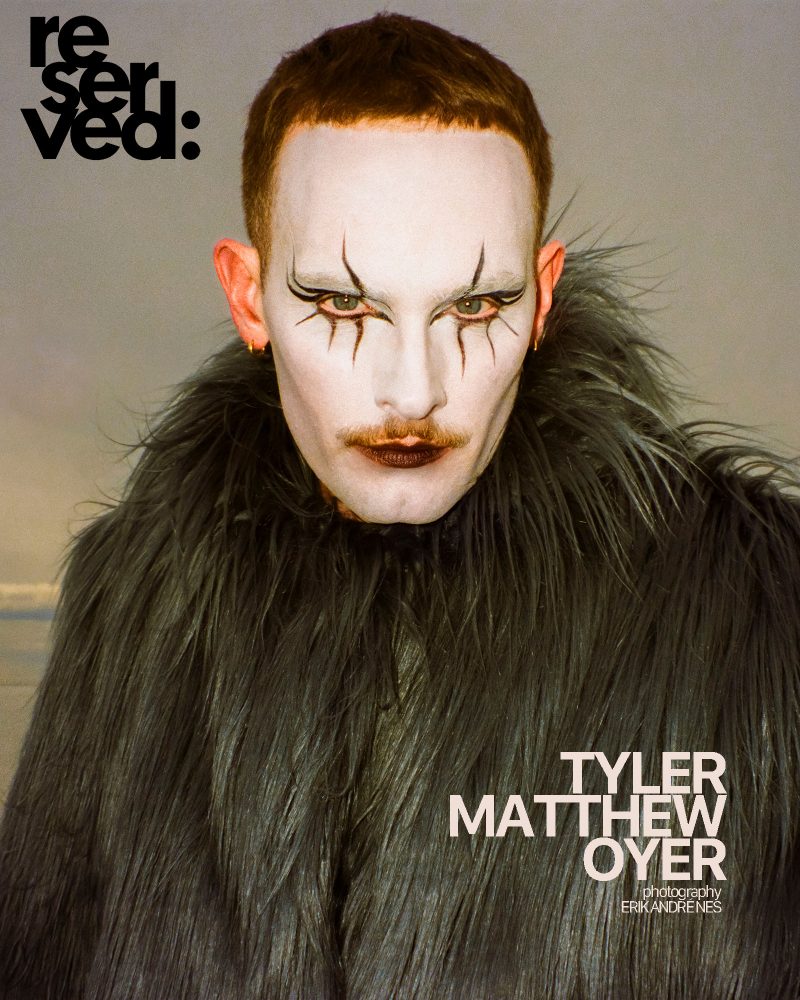

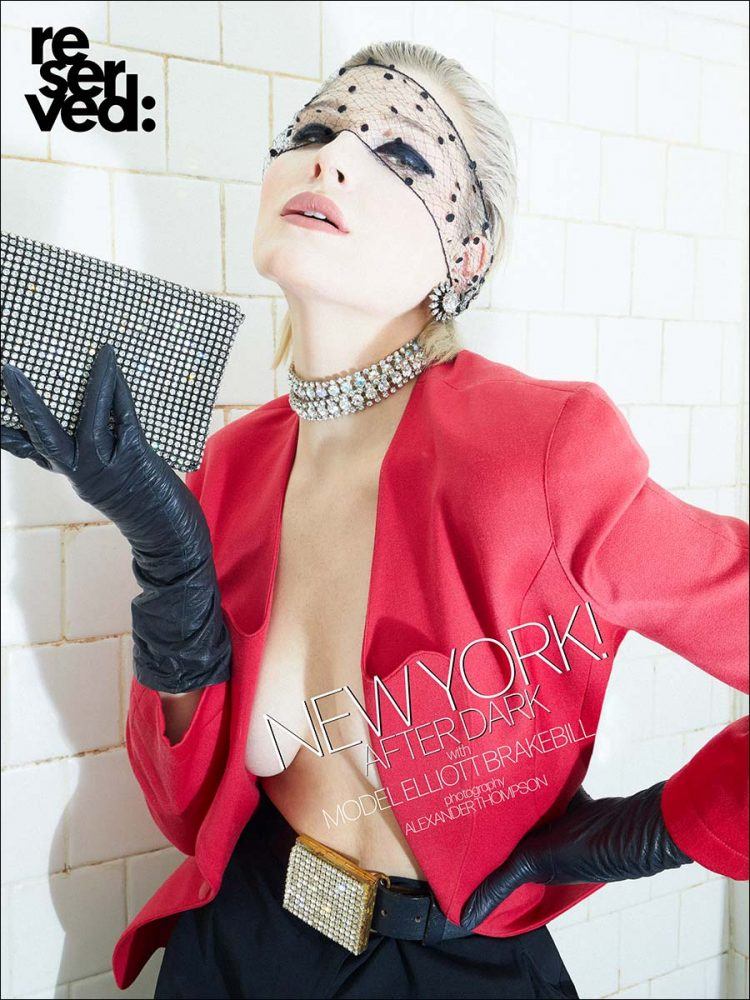

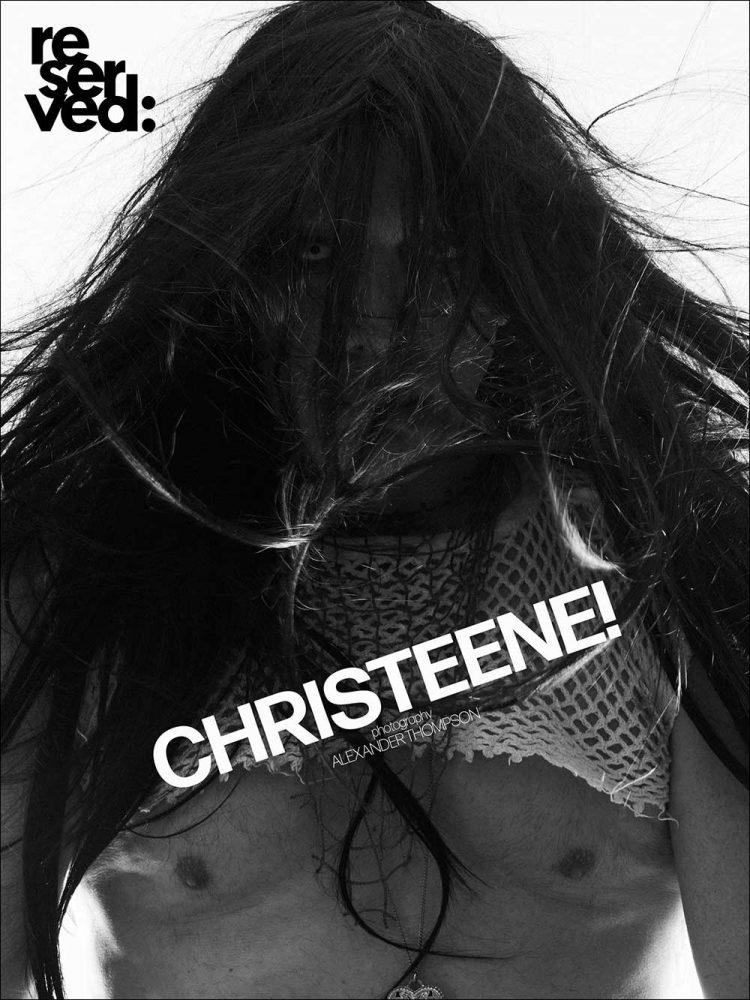

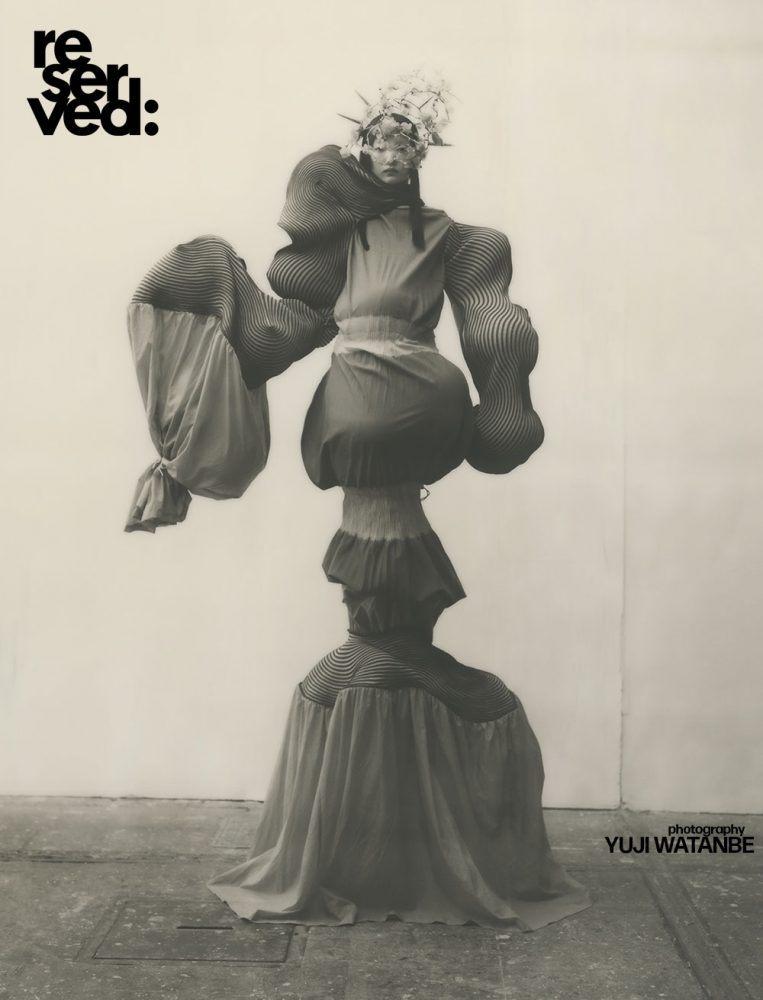

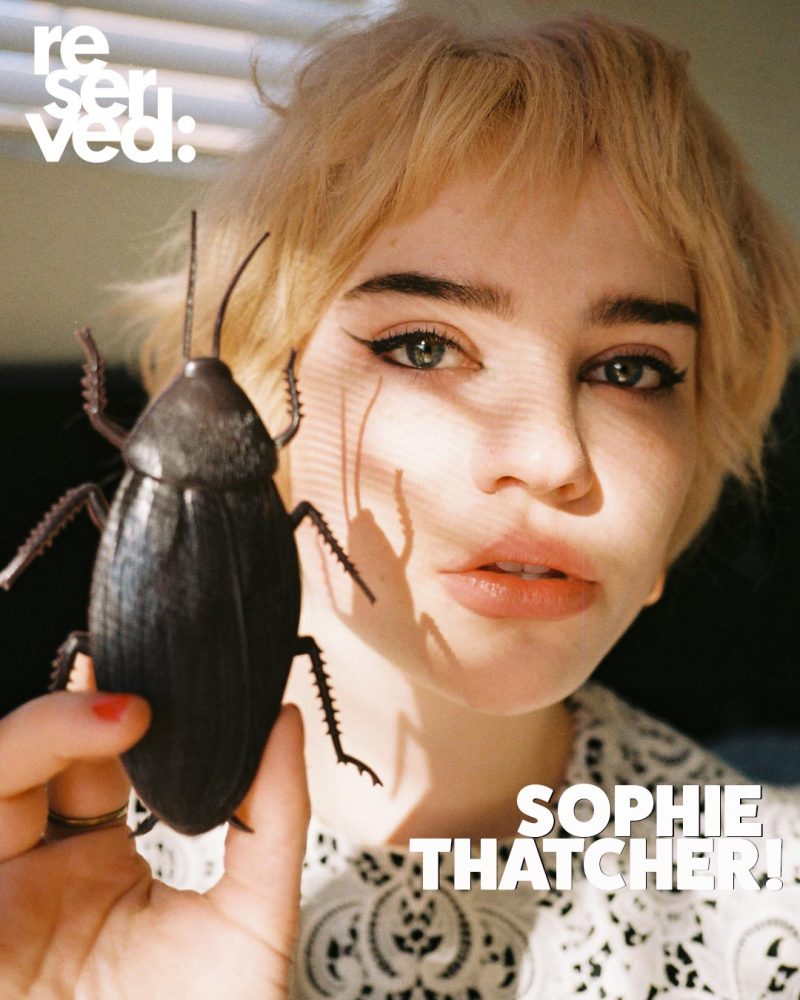

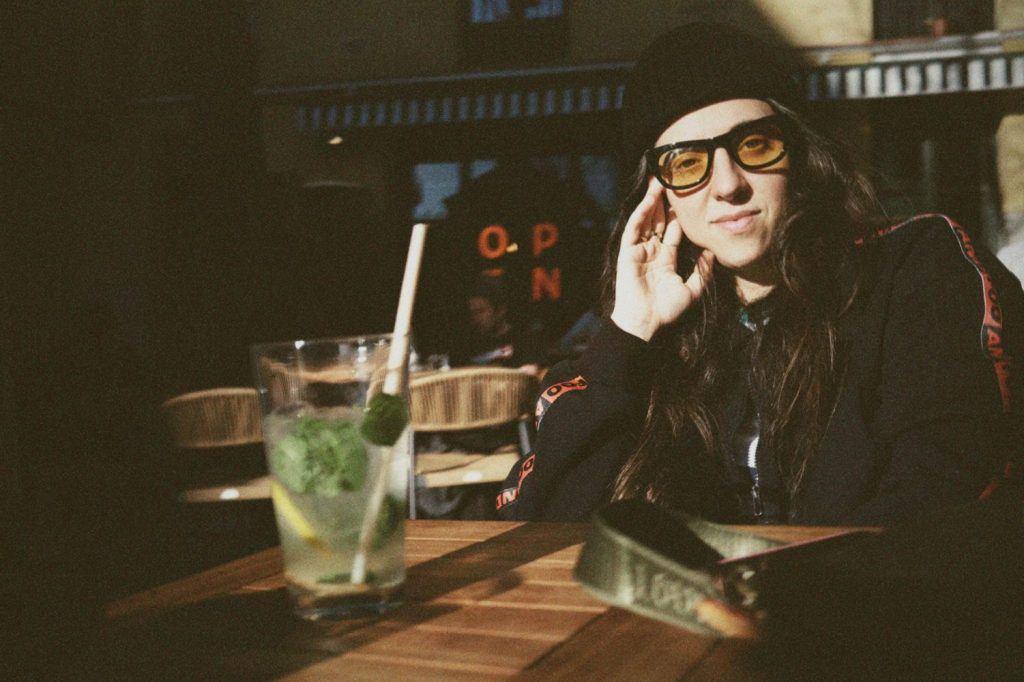

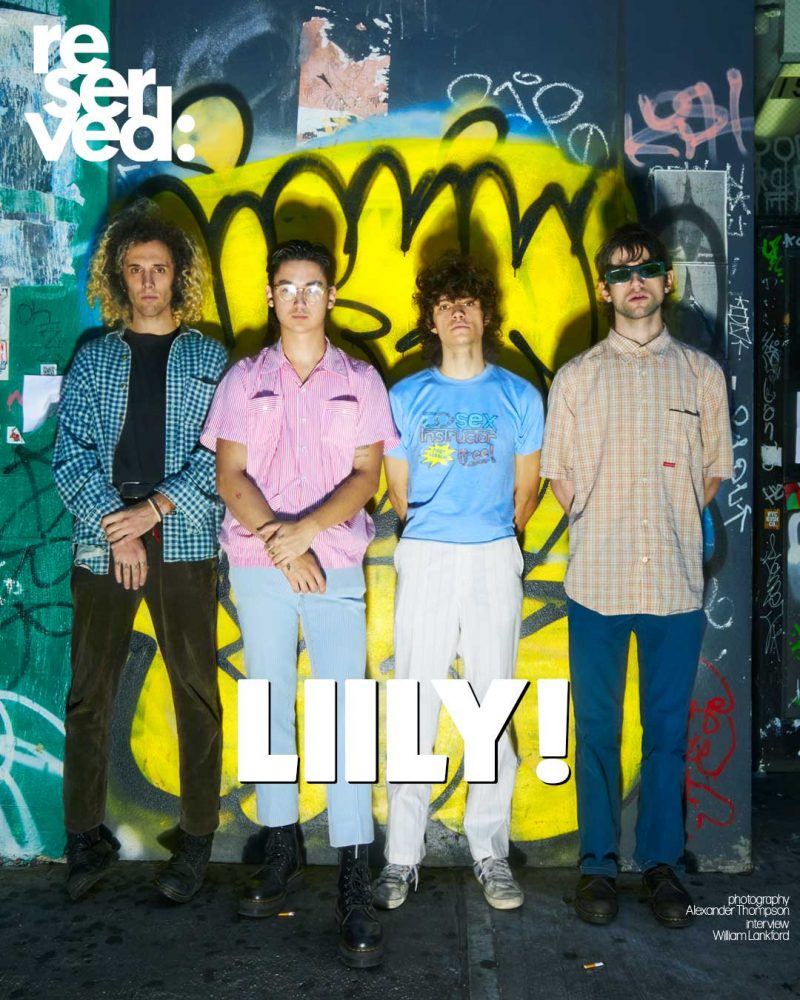

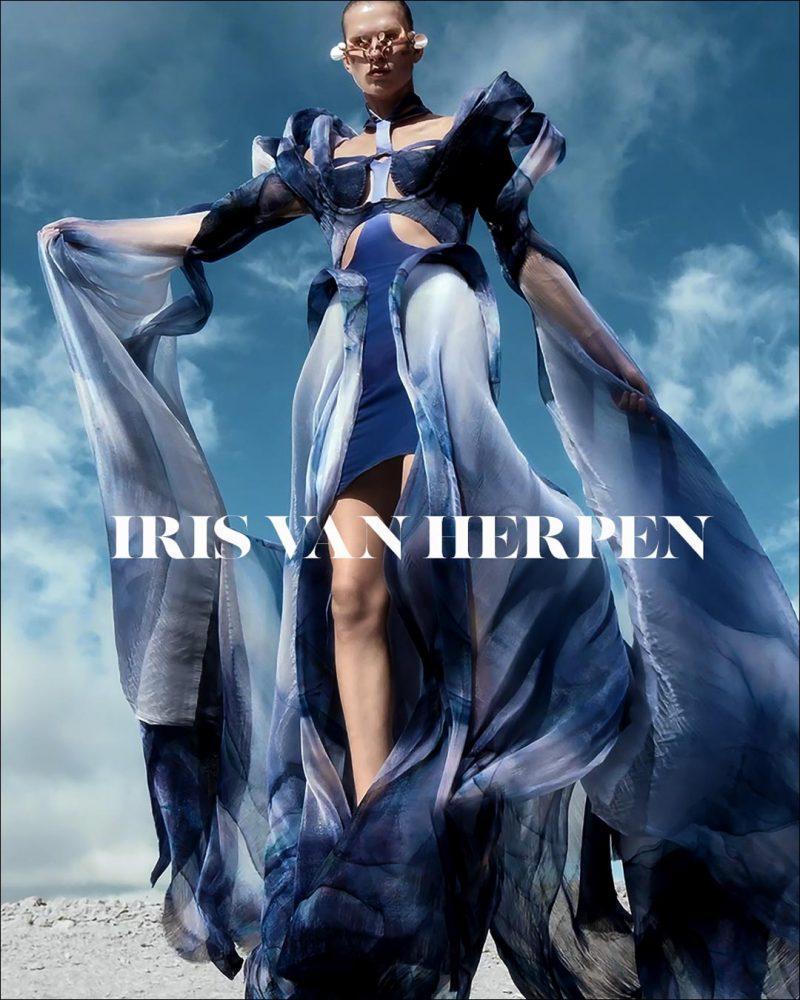

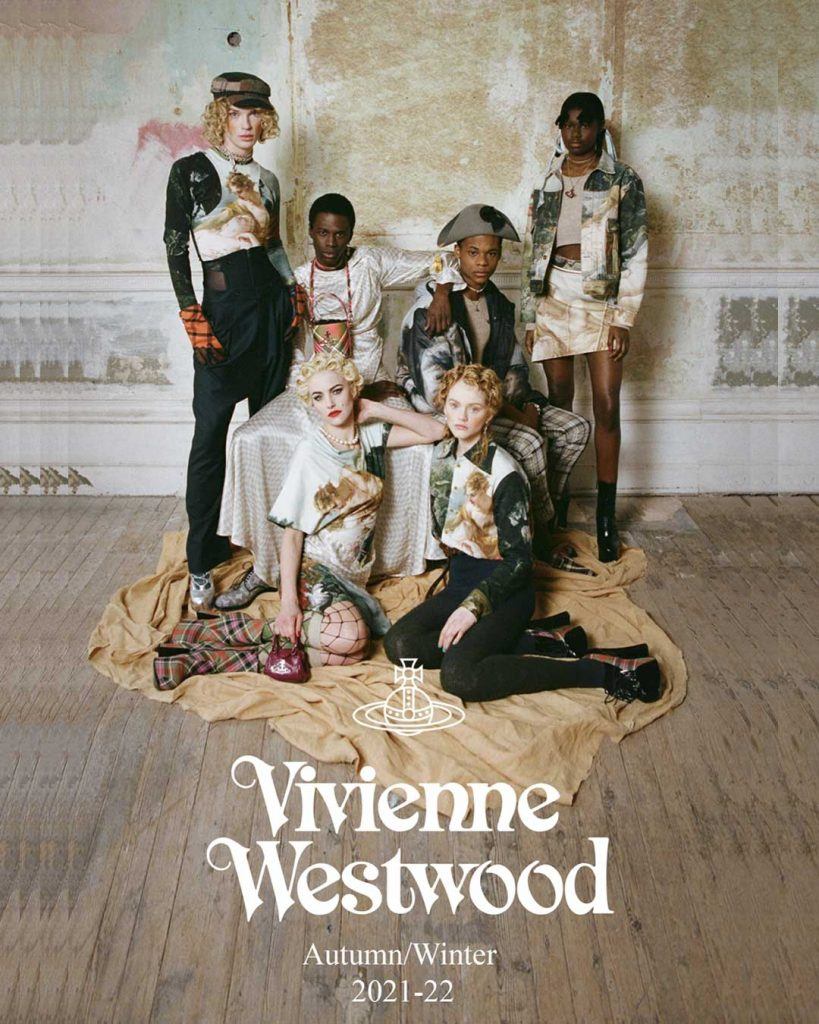

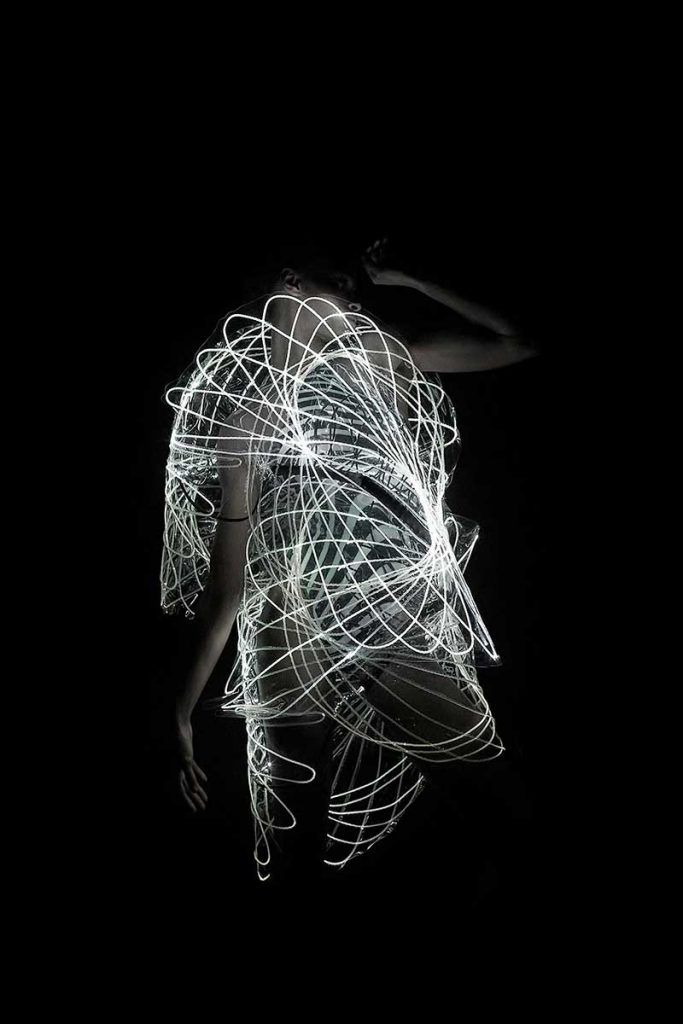

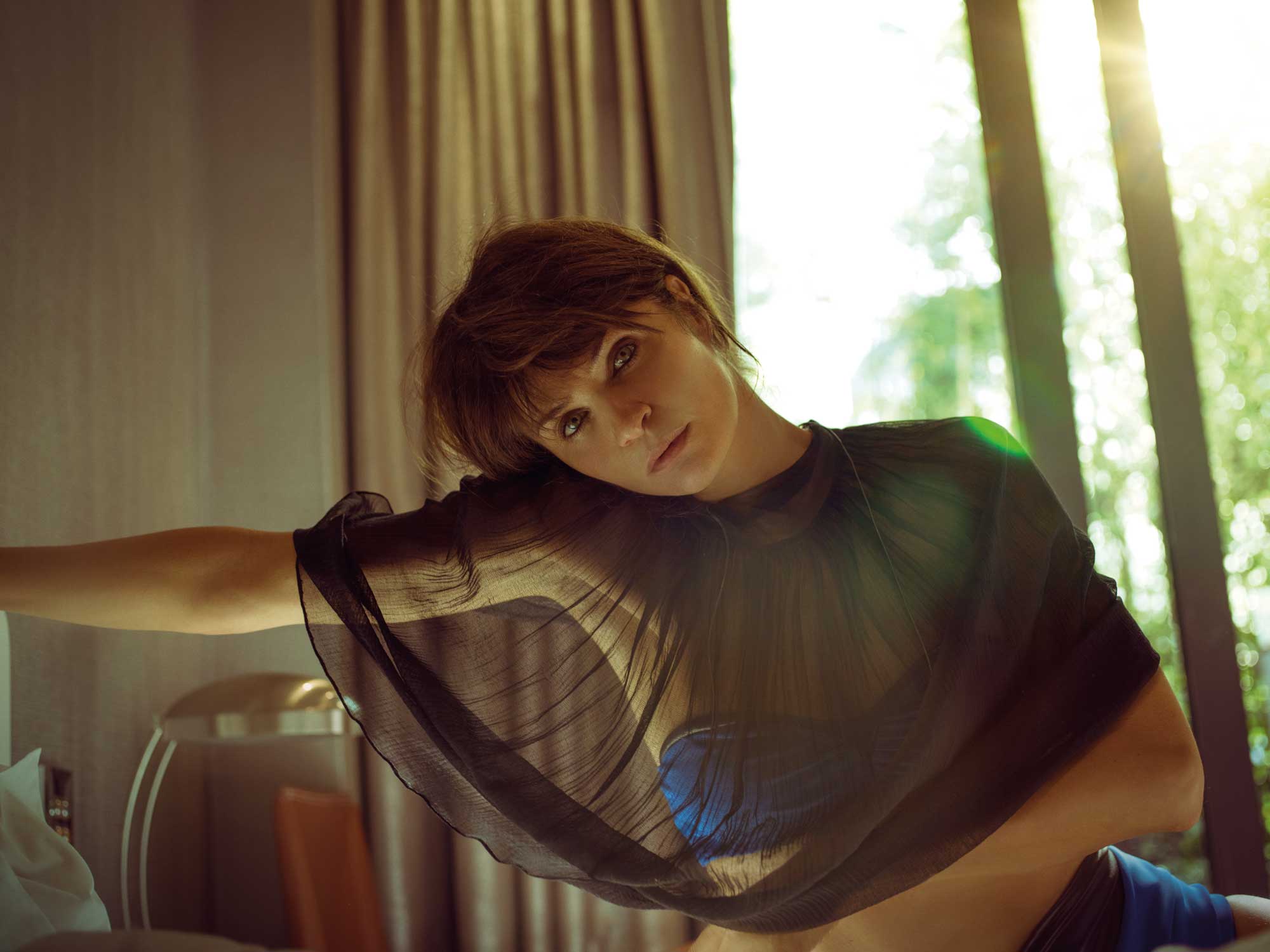

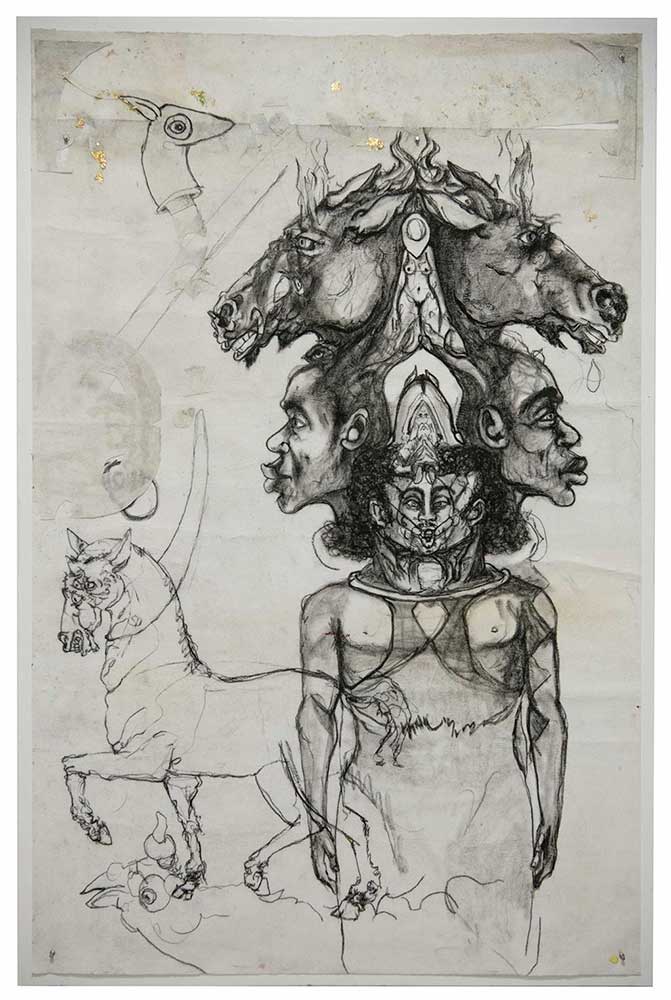

Untitled by artist Angelbert Metoyer.

It sounds like it’s the emotional and spiritual journey of the process that is the most important aspect of art making for you…

Definitely, man. It’s the only reason I keep working, in a sense – it’s always about reaching for something more. Even, if I’m thinking about a specific theme, or some kind of response to something I heard or went through, there’s always this kind of immediacy in the process that sparks different types of transitions, and I just try to take hold of them, and complete them. That why I work on multiple things at the same time – I’ll be completing one thing that the energy I’m making my request to is kind of allowing me to create, and then, at the same time, maybe there’s a whole other thing that is opening up through that window I’ve created. I actually sometimes try to not sell works unless the person buying it is really connected to it. And if I can see that connection, then I know immediately that the work was always meant for them. It’s not about money, or anything, at that point. It’s more like being able to see that what the work is giving that person is something more than was initially asked for when I was making it.

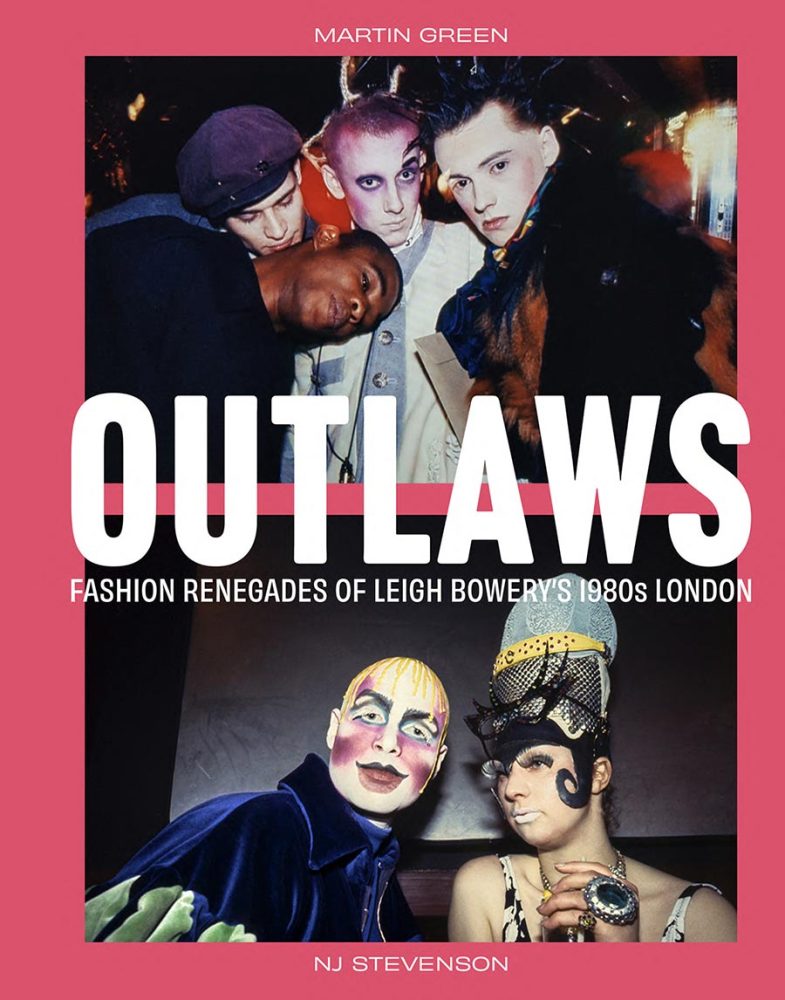

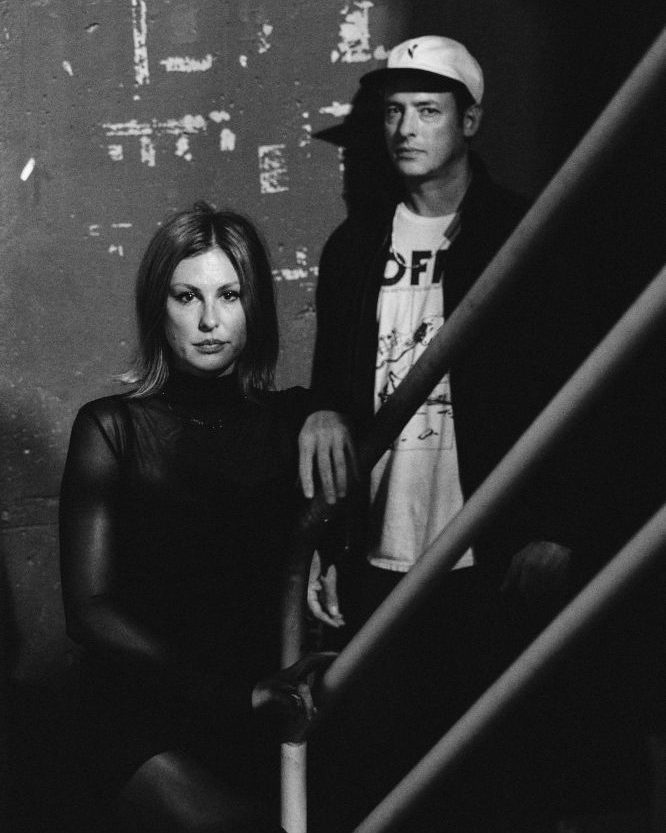

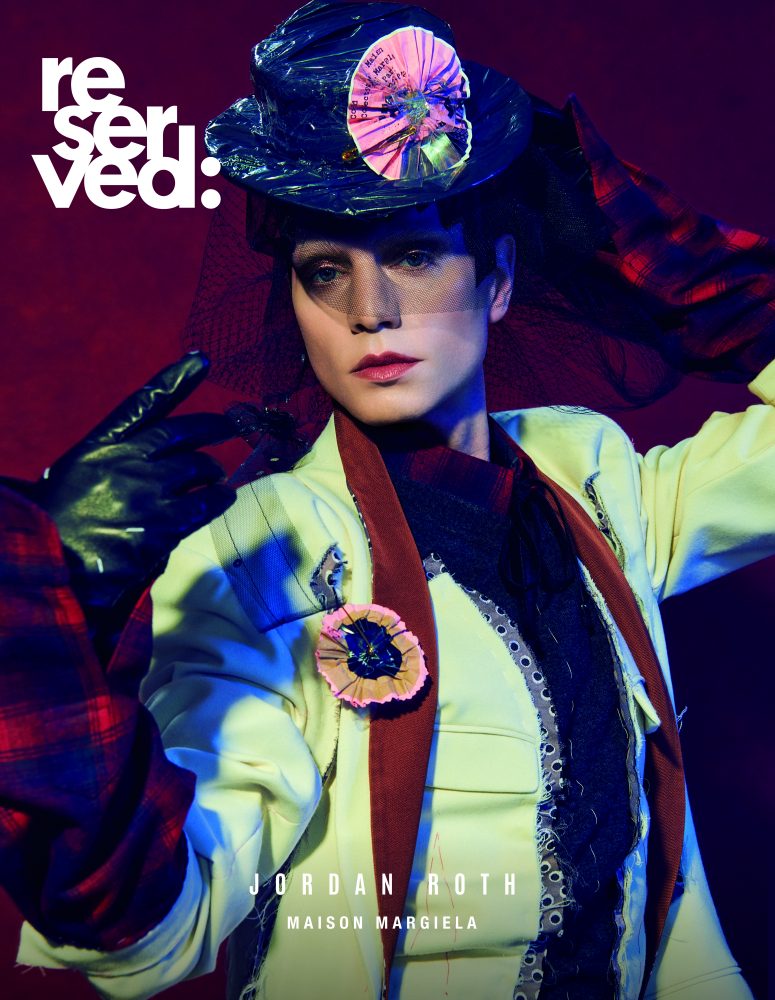

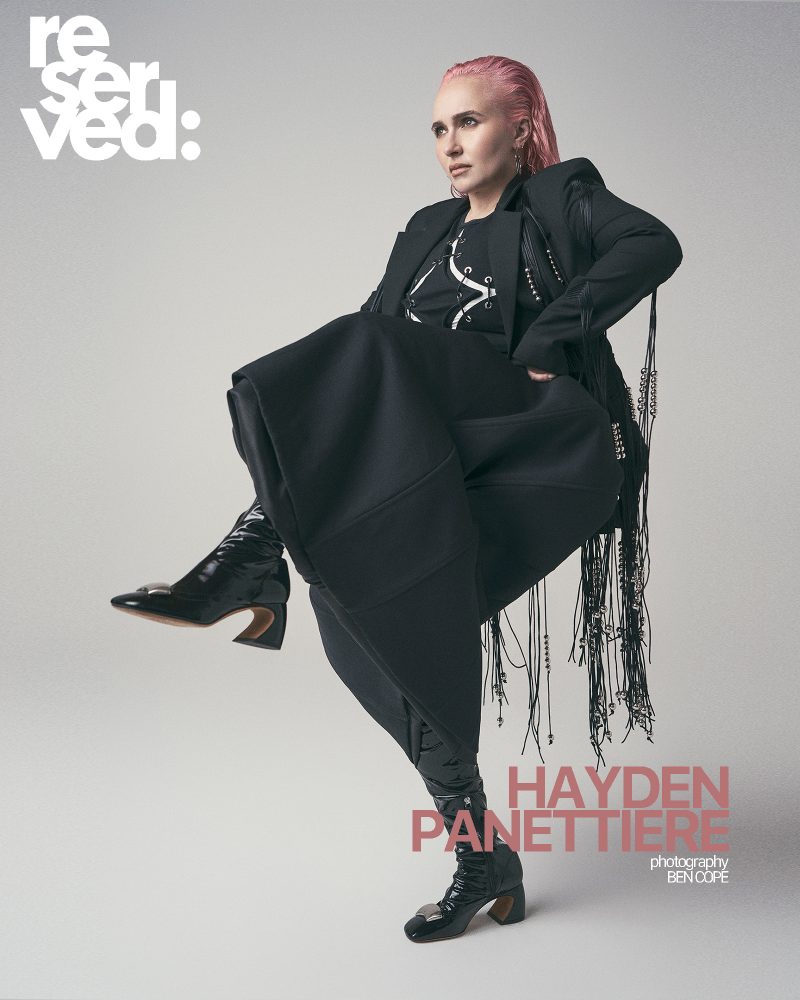

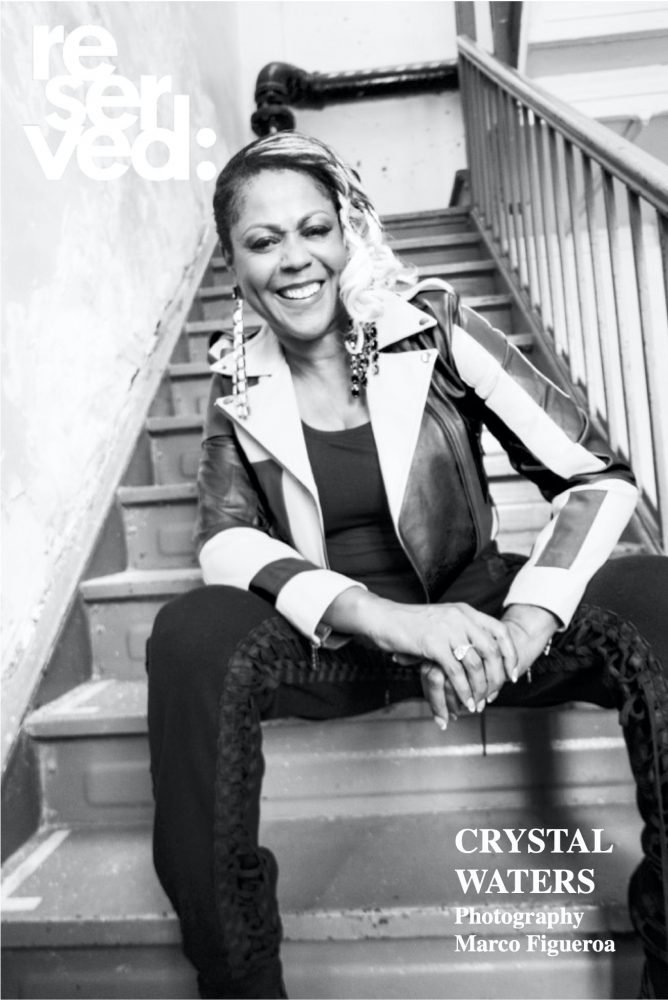

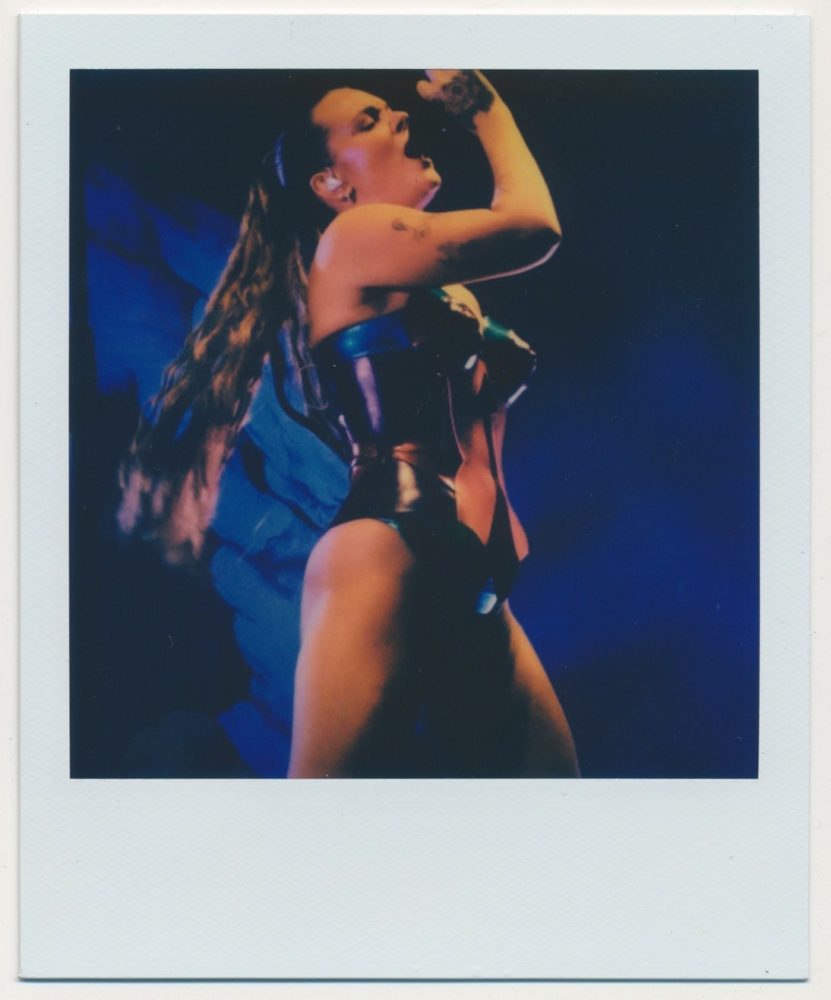

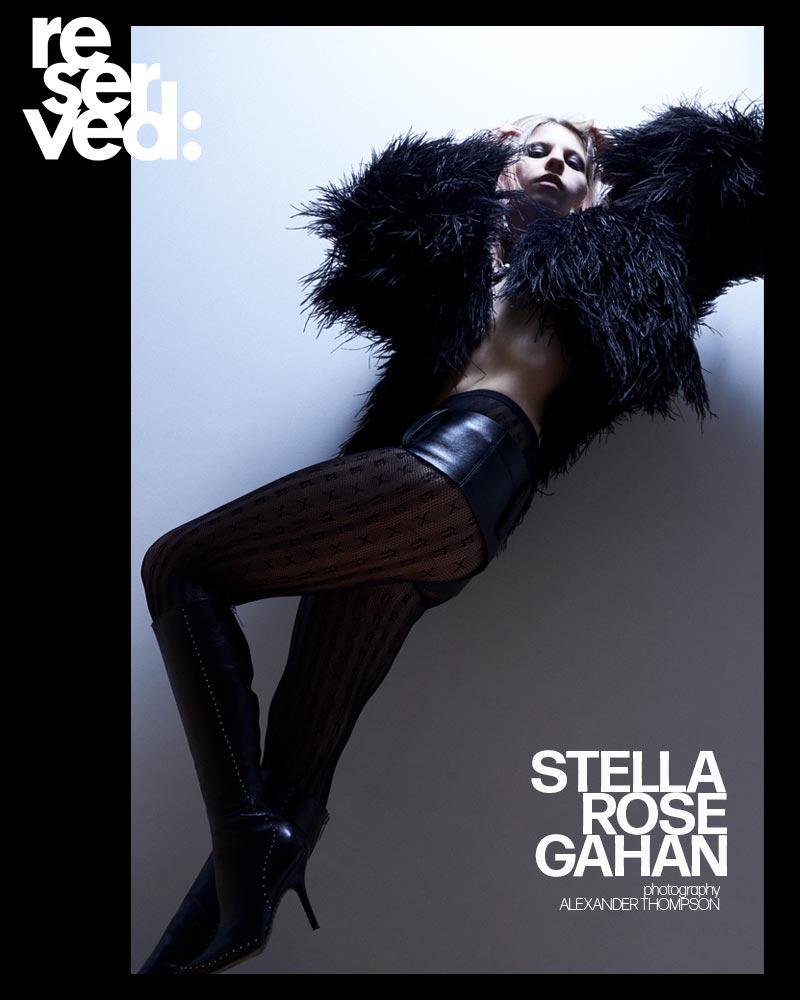

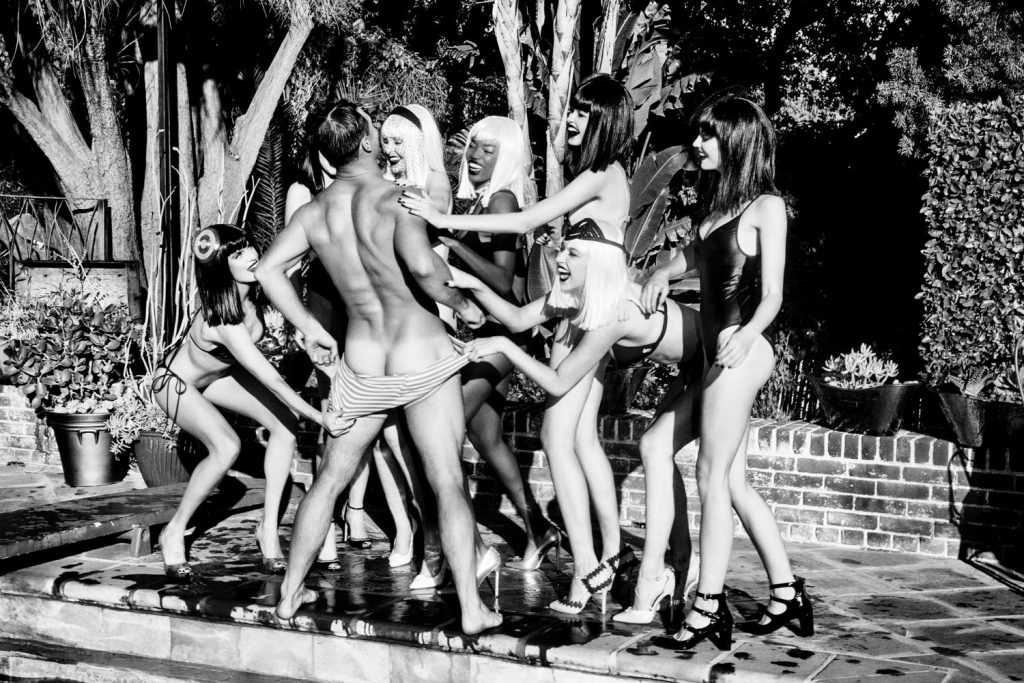

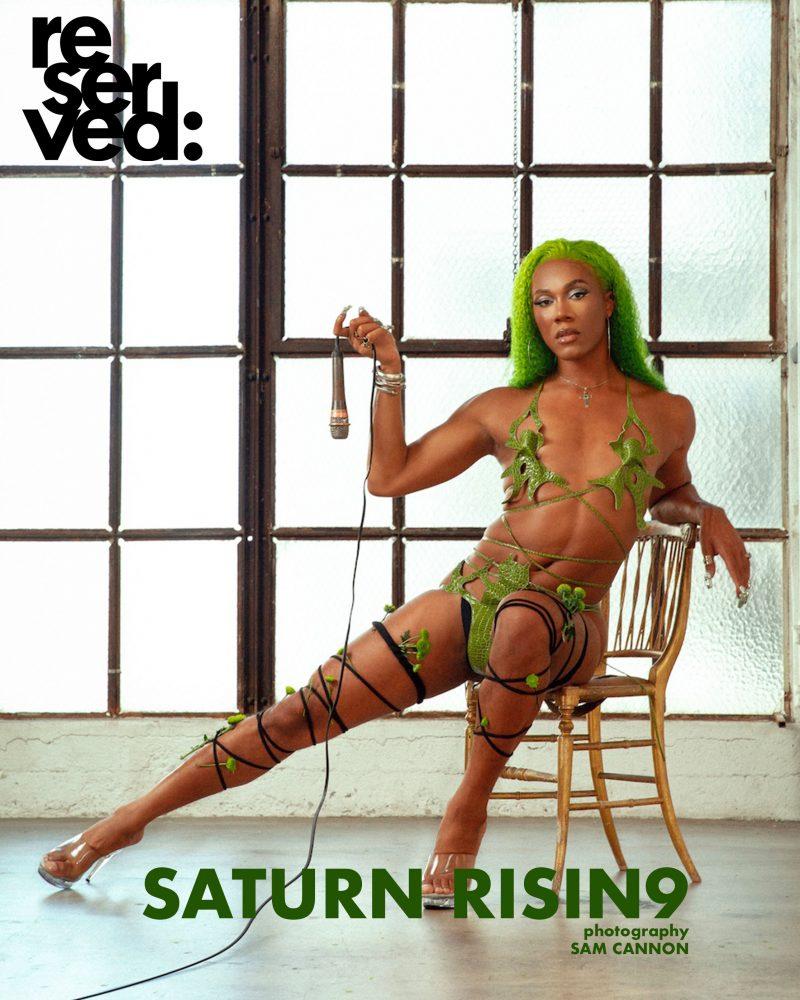

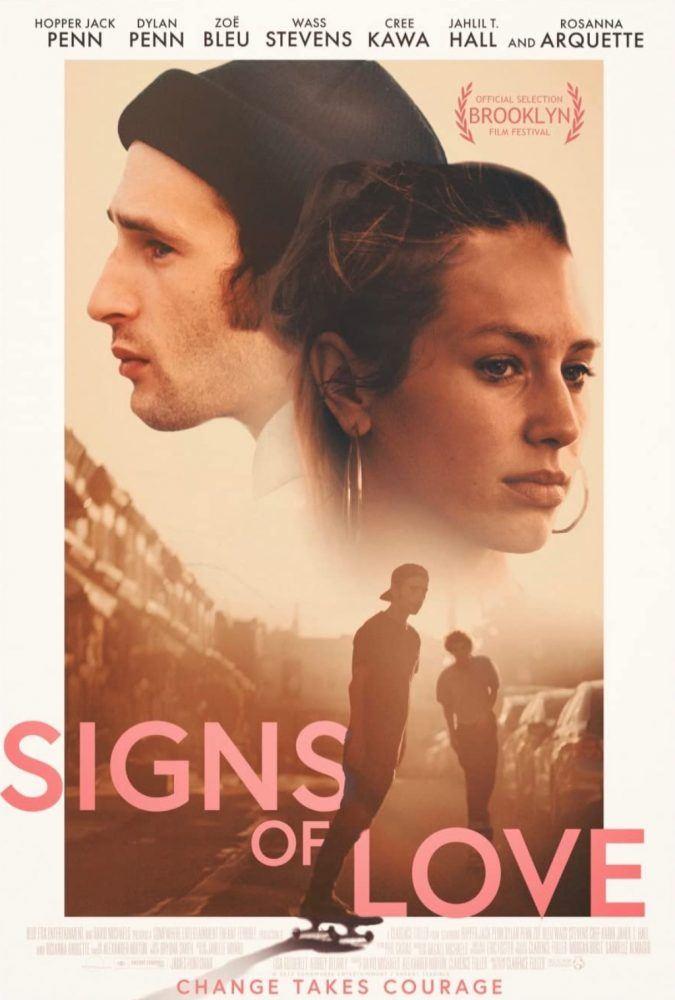

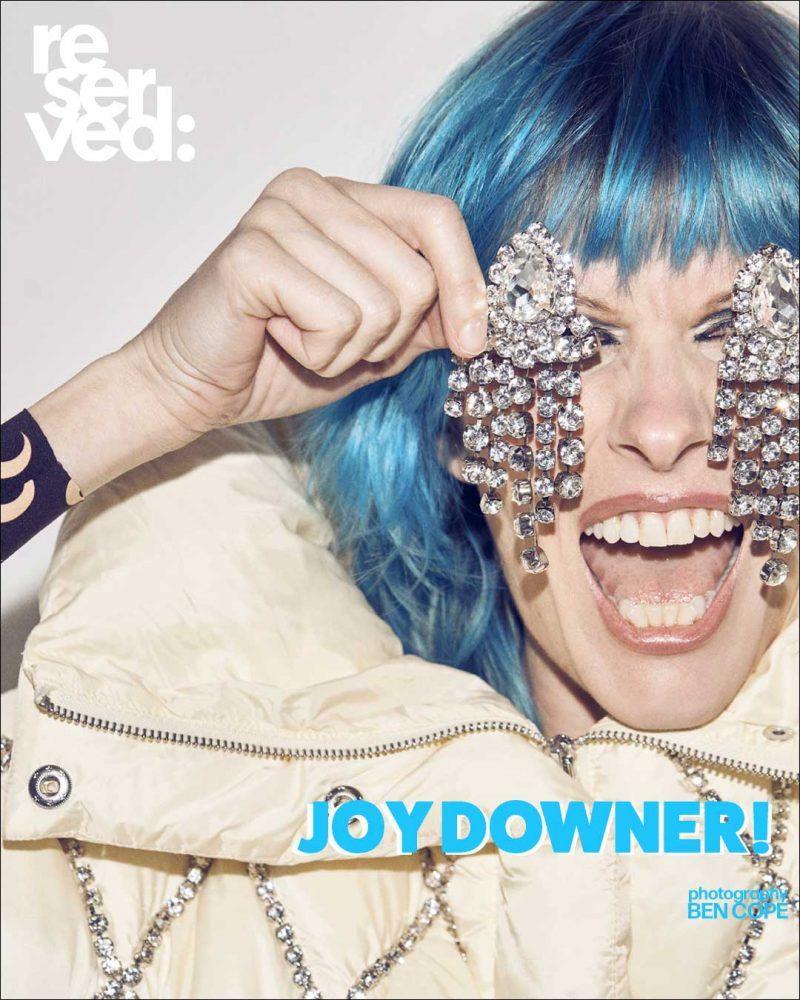

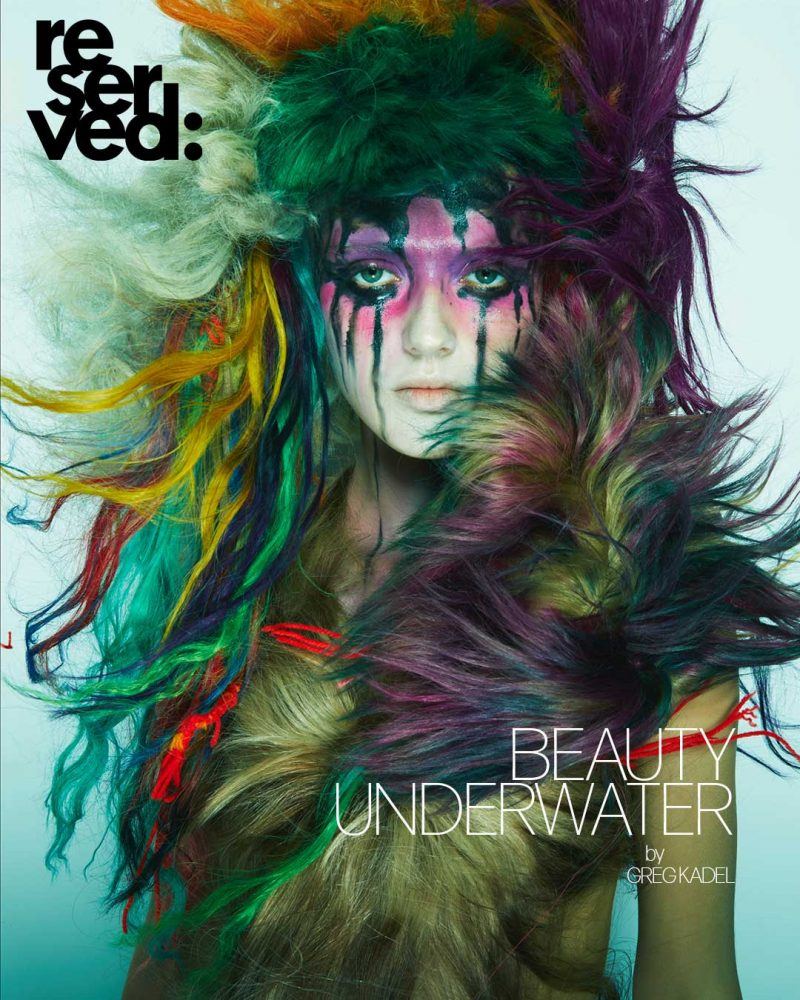

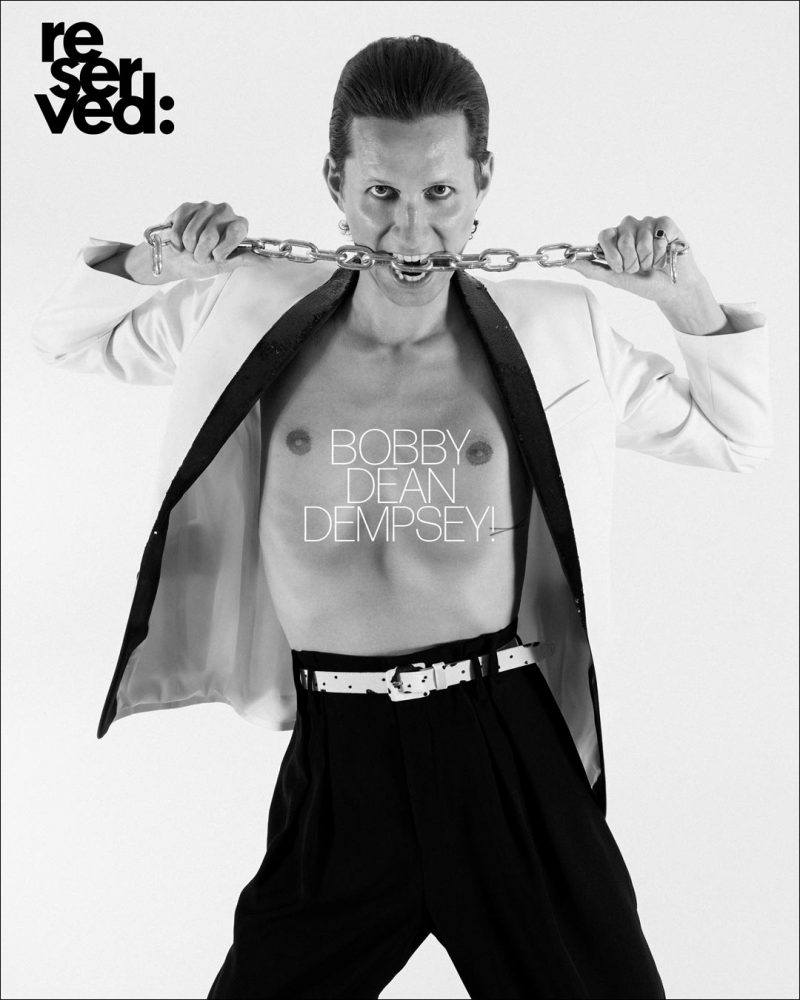

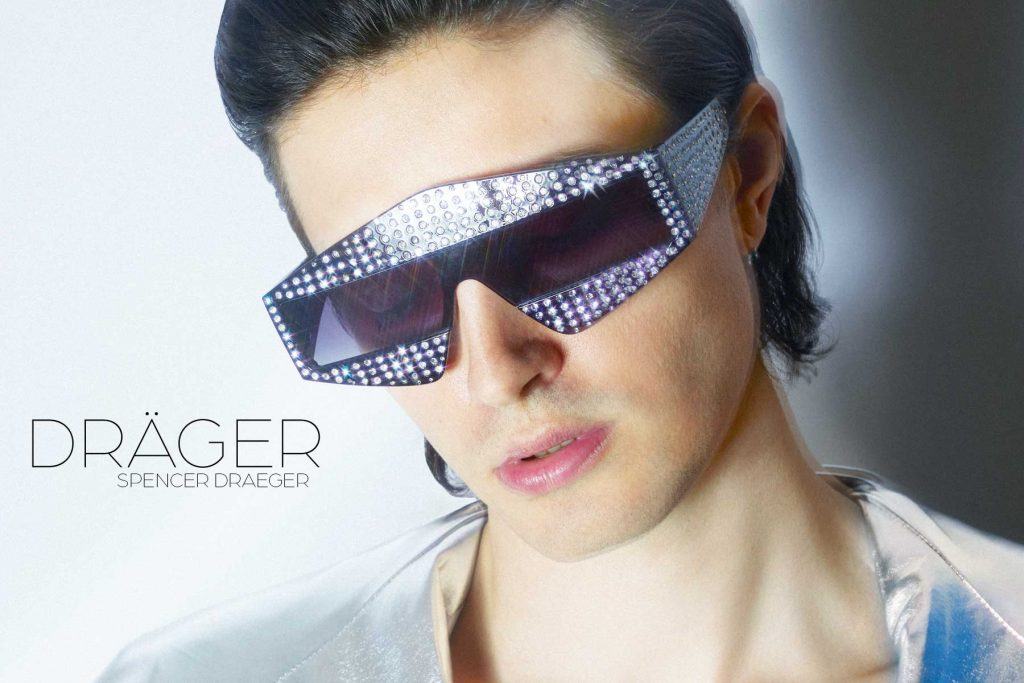

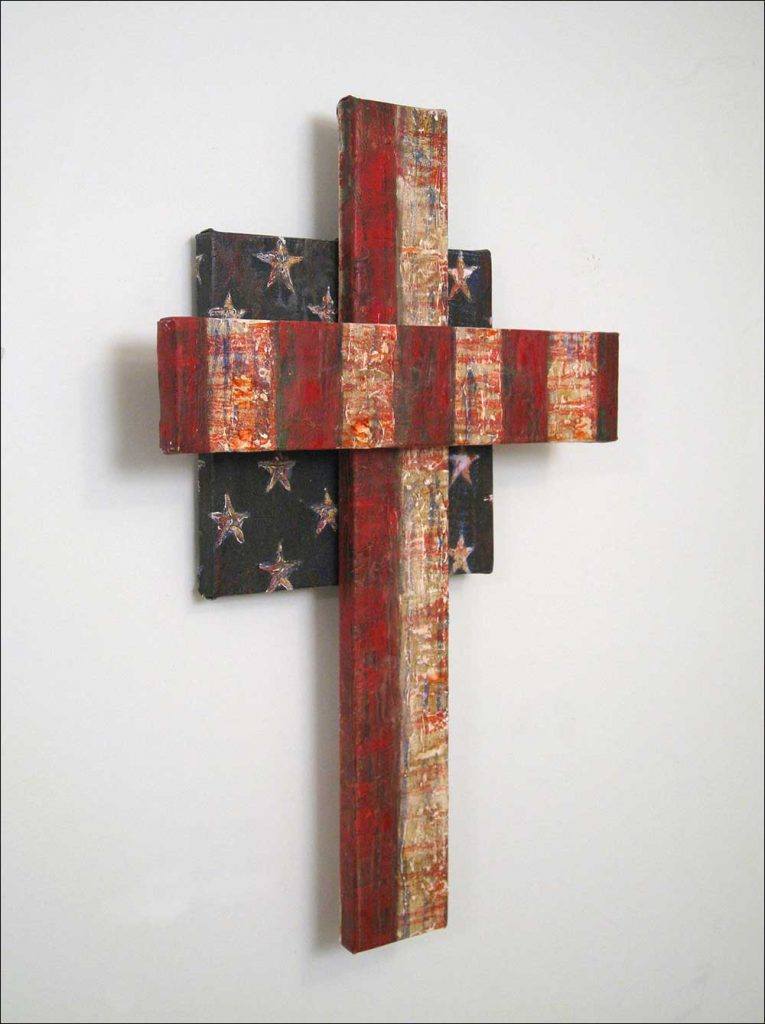

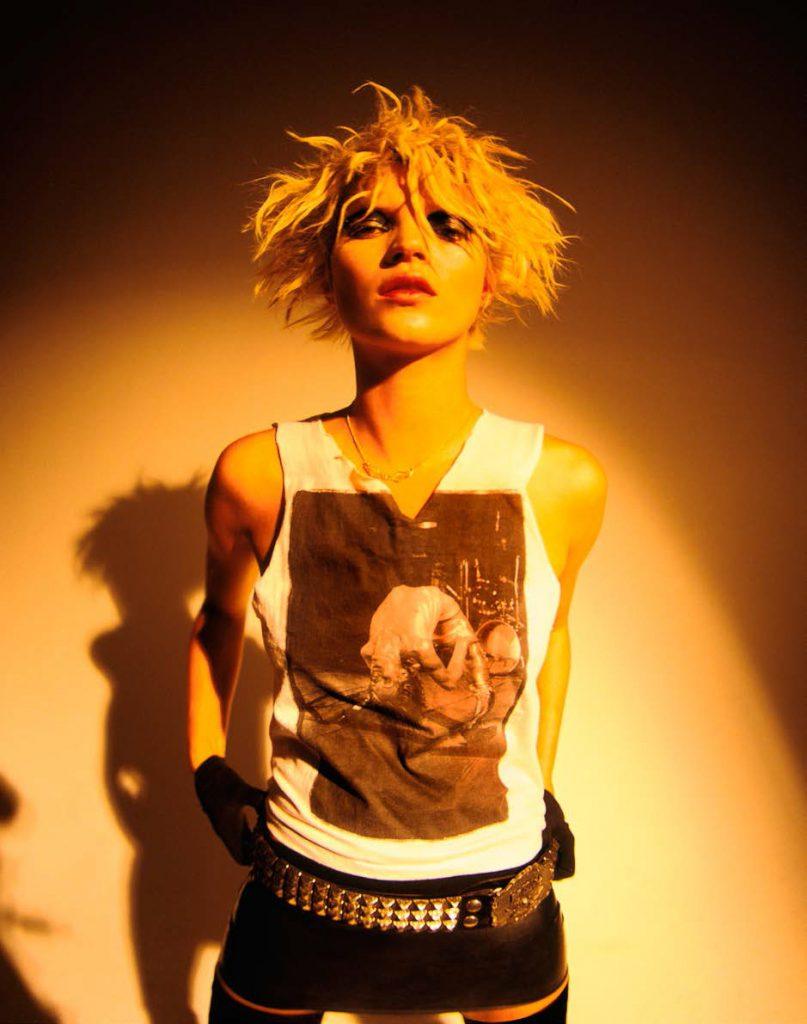

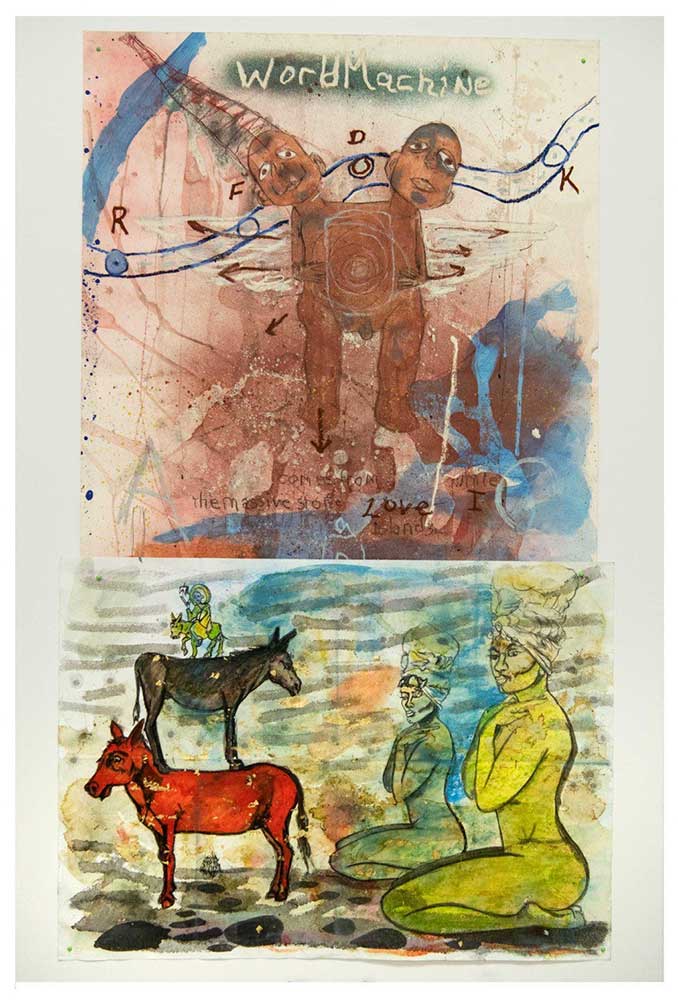

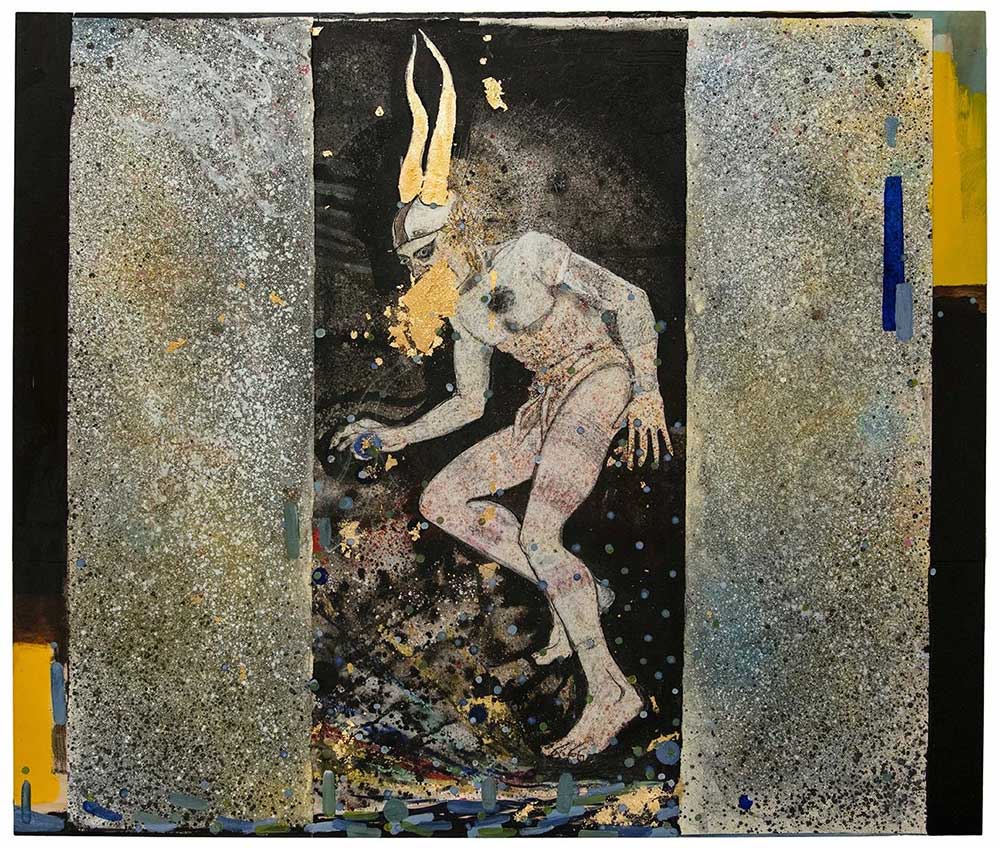

World Machine by artist Angelbert Metoyer.

You made the work for the current show in The Hamptons, what made you want to create a body of work in that part of the world….

I have been coming here off-season to paint every other year for a decade and a half, maybe more. There’s a certain perception of The Hamptons, of course, but when you are here off-season it’s actually a very spiritual place, and I get why the history of American painting kind of began here. When you’re amongst the people who actually live here, it’s a soulful place, a really spiritual zone that is some kind of vortex of very subtle but powerful emotion. I feel like something about my work desires to be created in these kinds of settings, and the only other places I truly feel that in terms of a place that I work in are Texas and Northern California, and it’s interesting to me because those places are filled with a very similar kind of energy. There’s a series of works in this show that I’ve been committed to long term – one of the pieces I’ve been working on for 15 years. When I see an exhibition, I want one of two things. I want to feel that it’s fresh – like every time I look at it, I want to feel like it was made today – and I also want to have that emotional response where it’s like, wow, I don’t know if this was made yesterday, or a hundred years ago. I think that all the works in this show express my desire to create this kind of timeless presence.

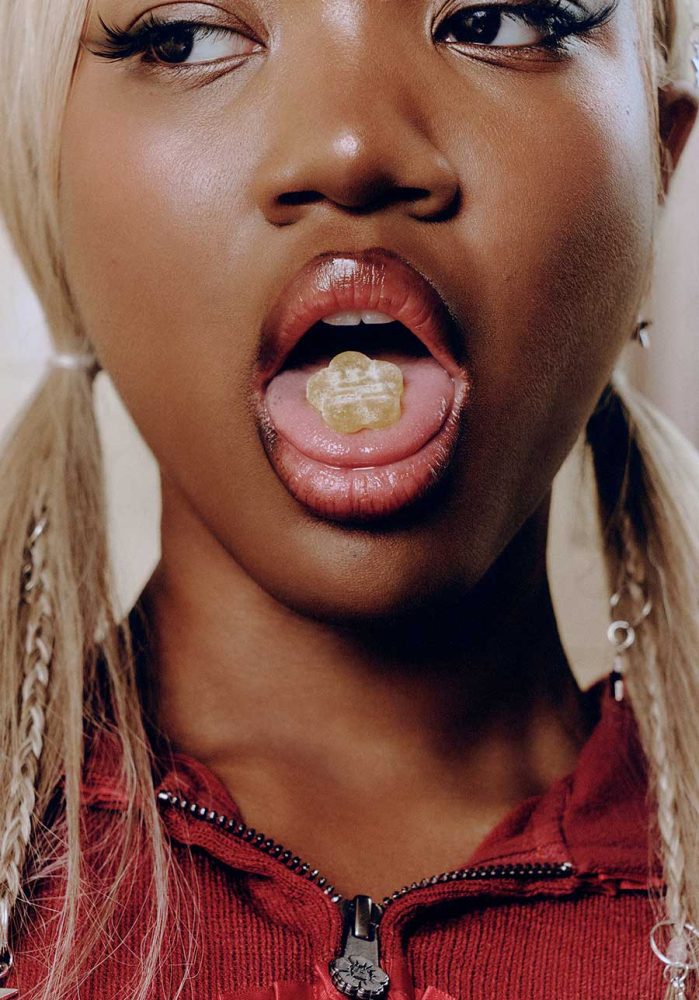

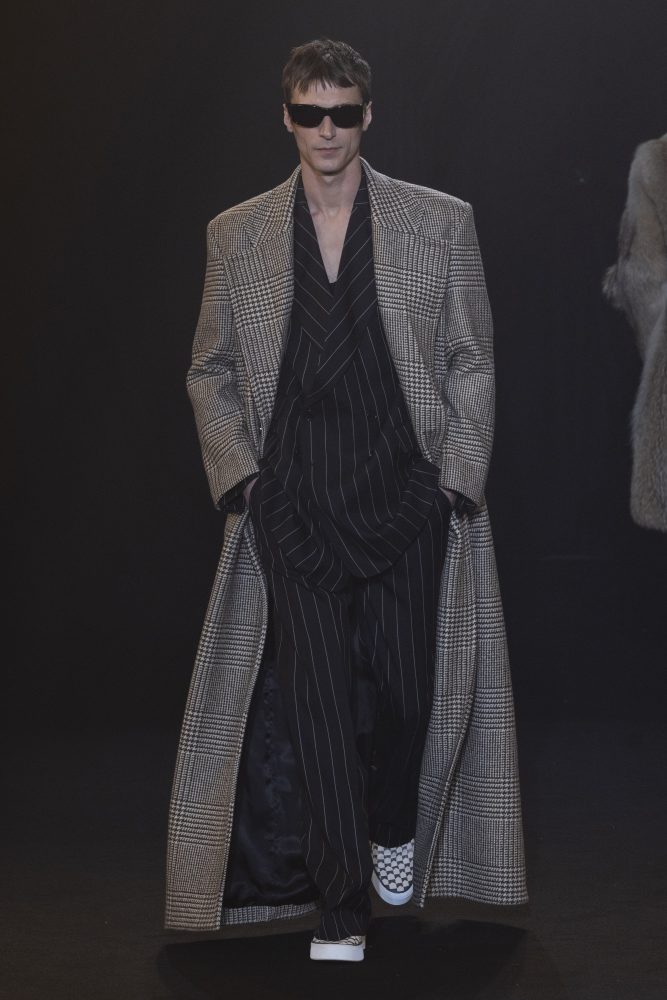

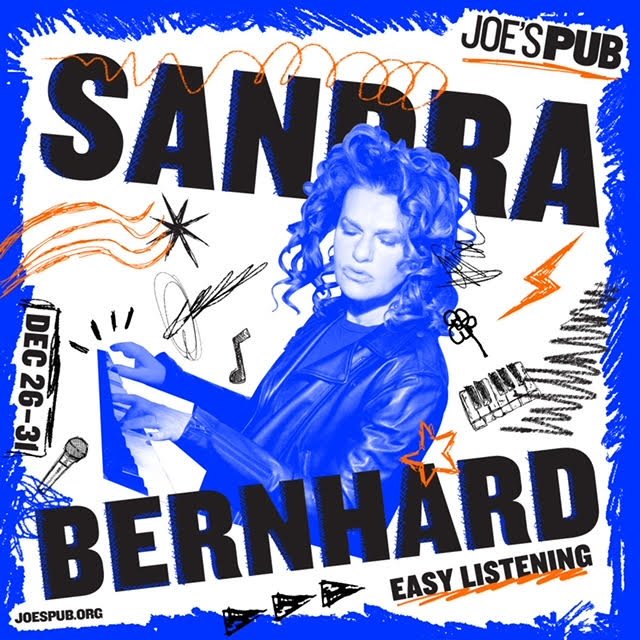

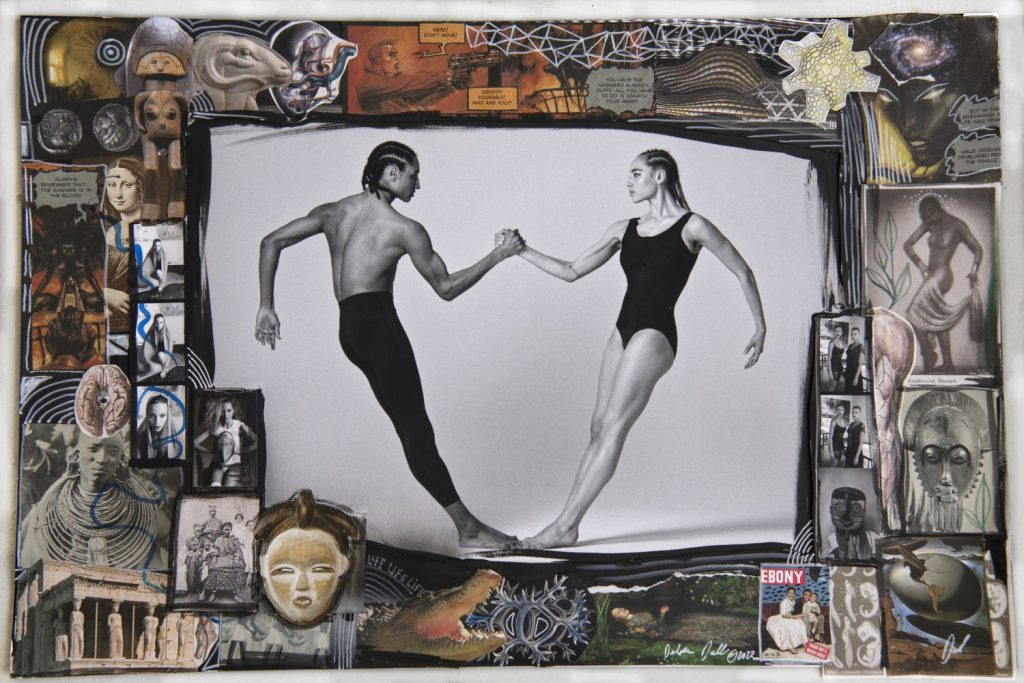

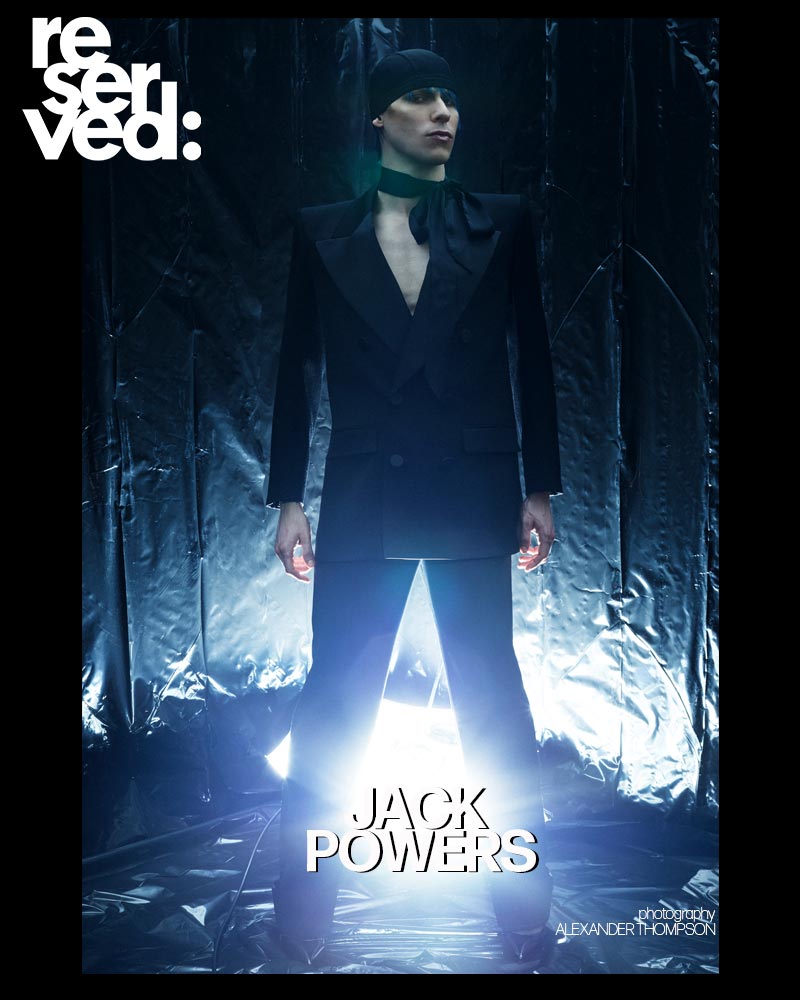

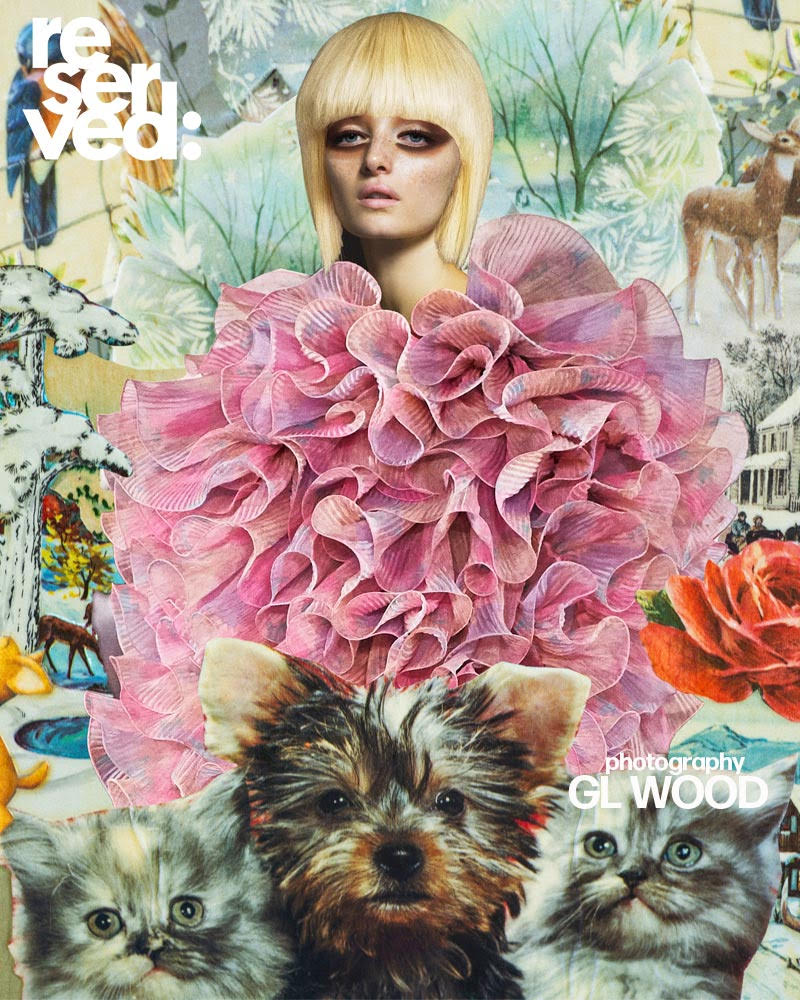

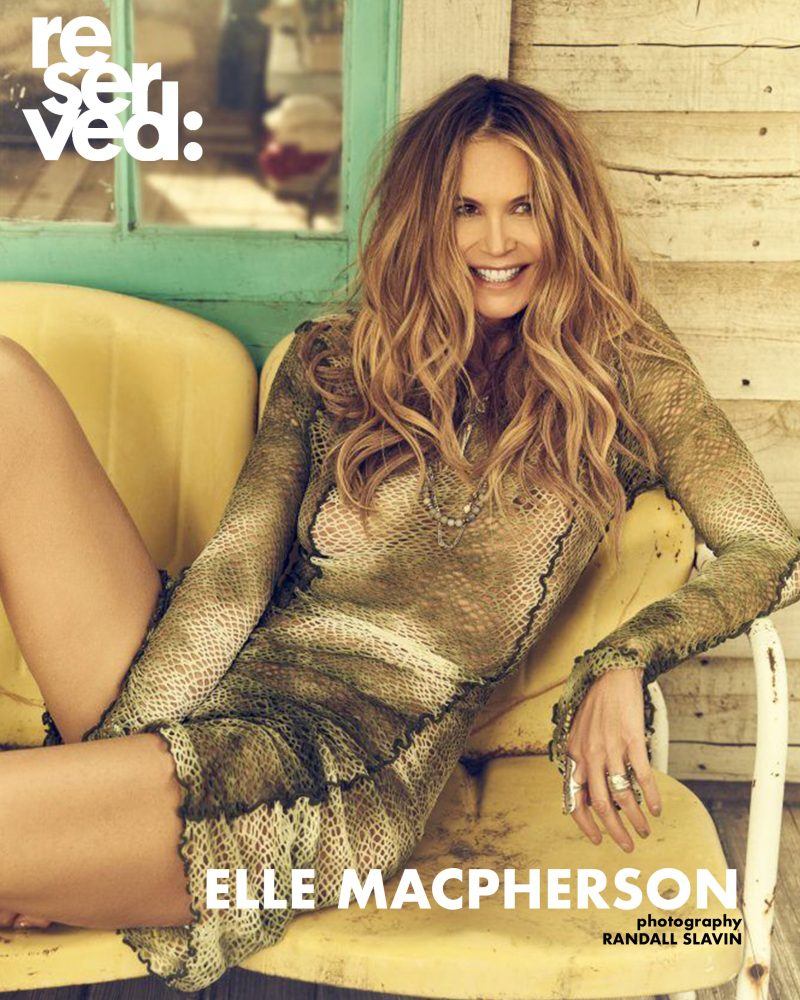

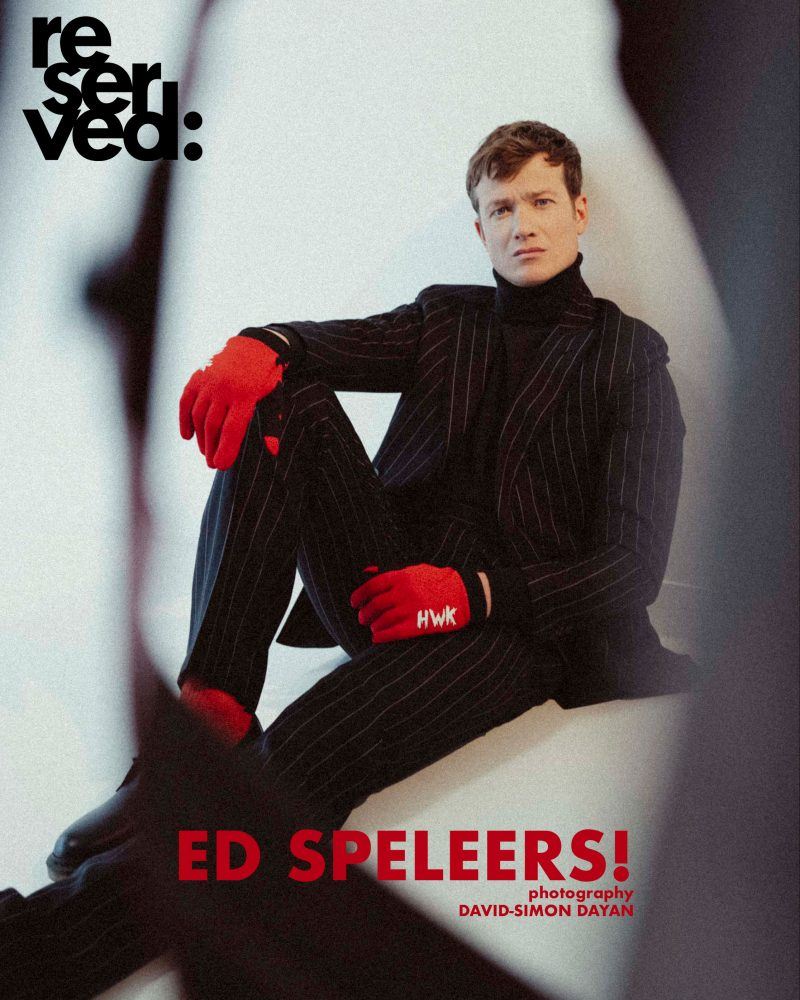

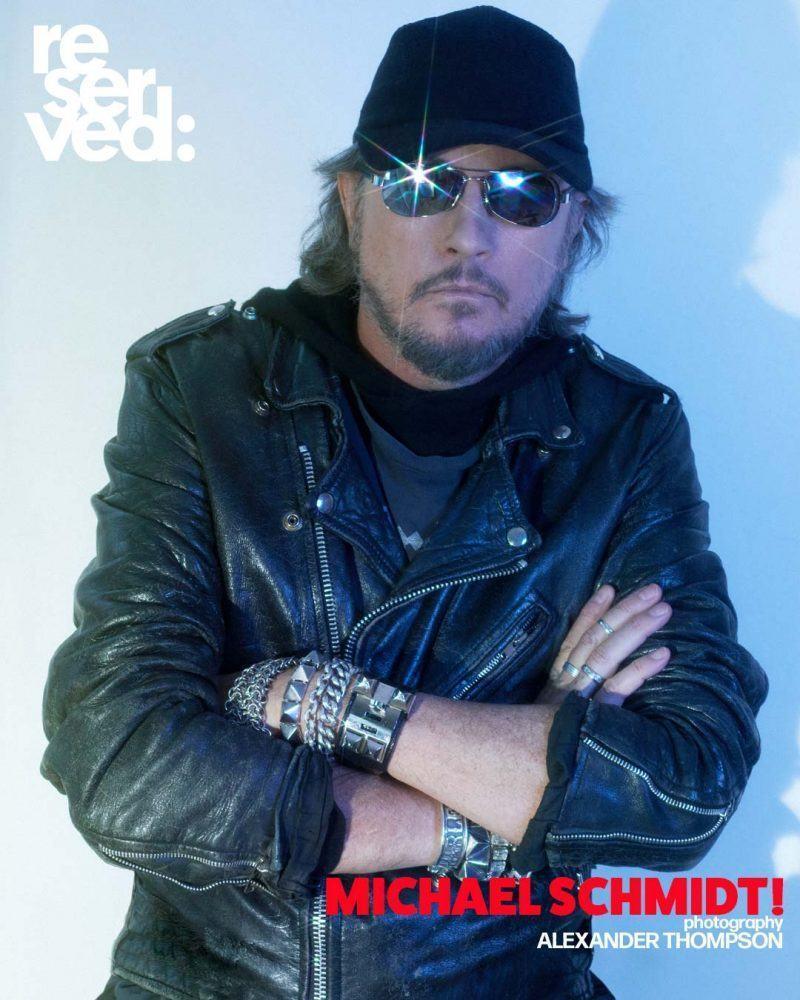

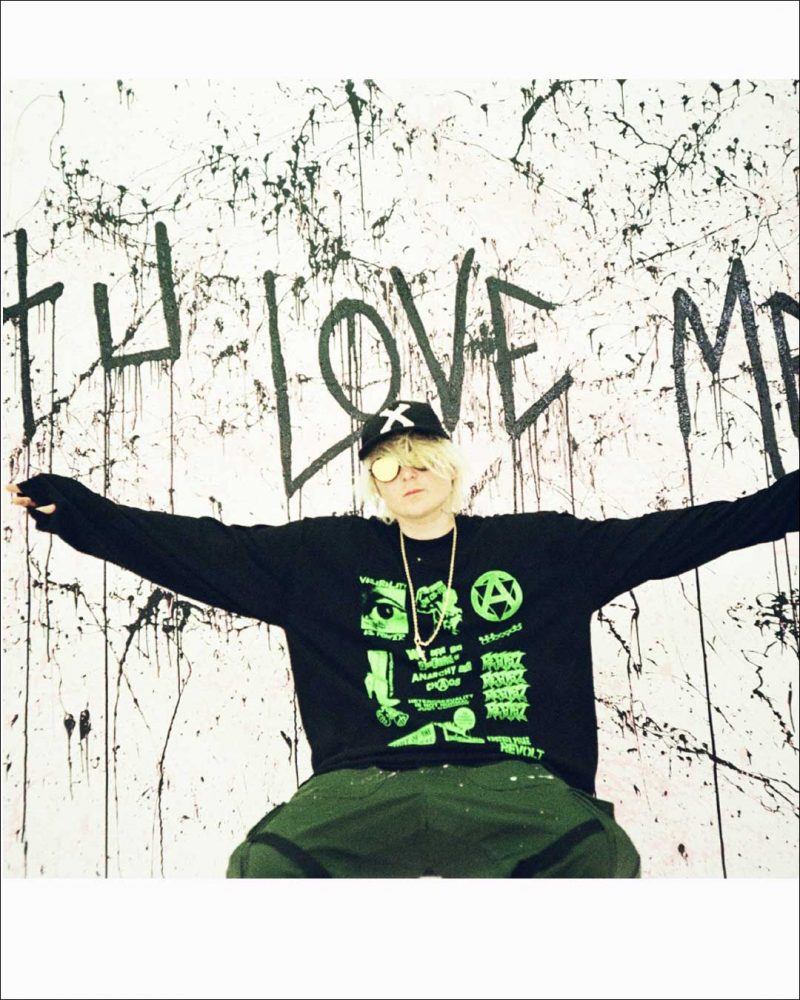

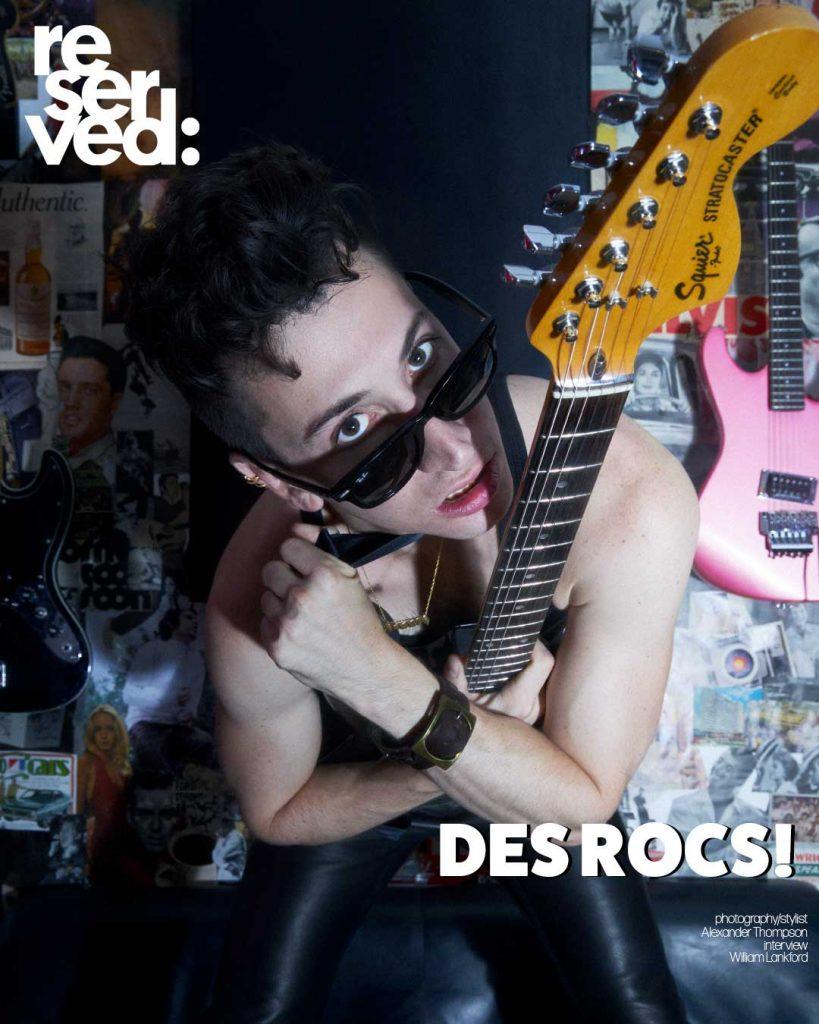

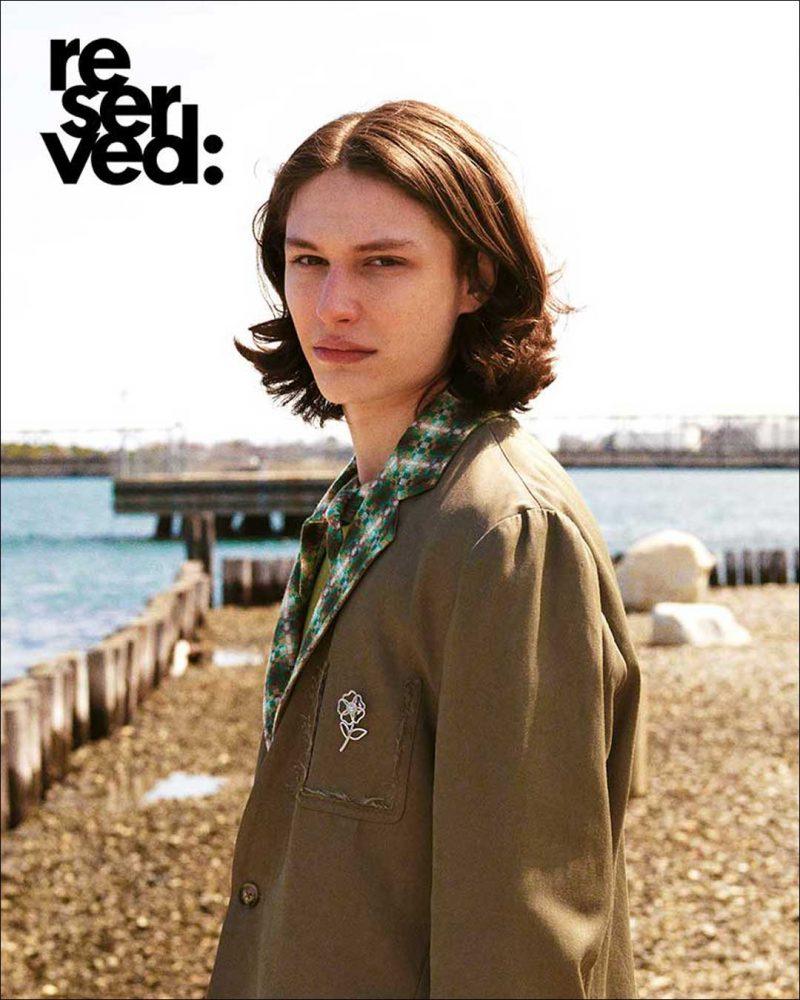

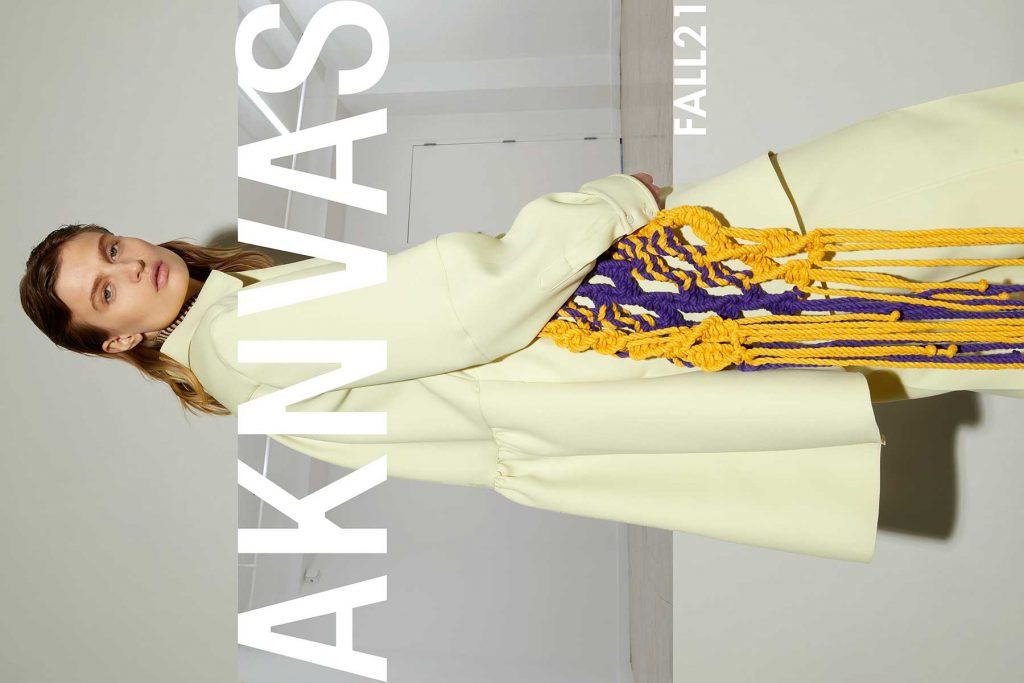

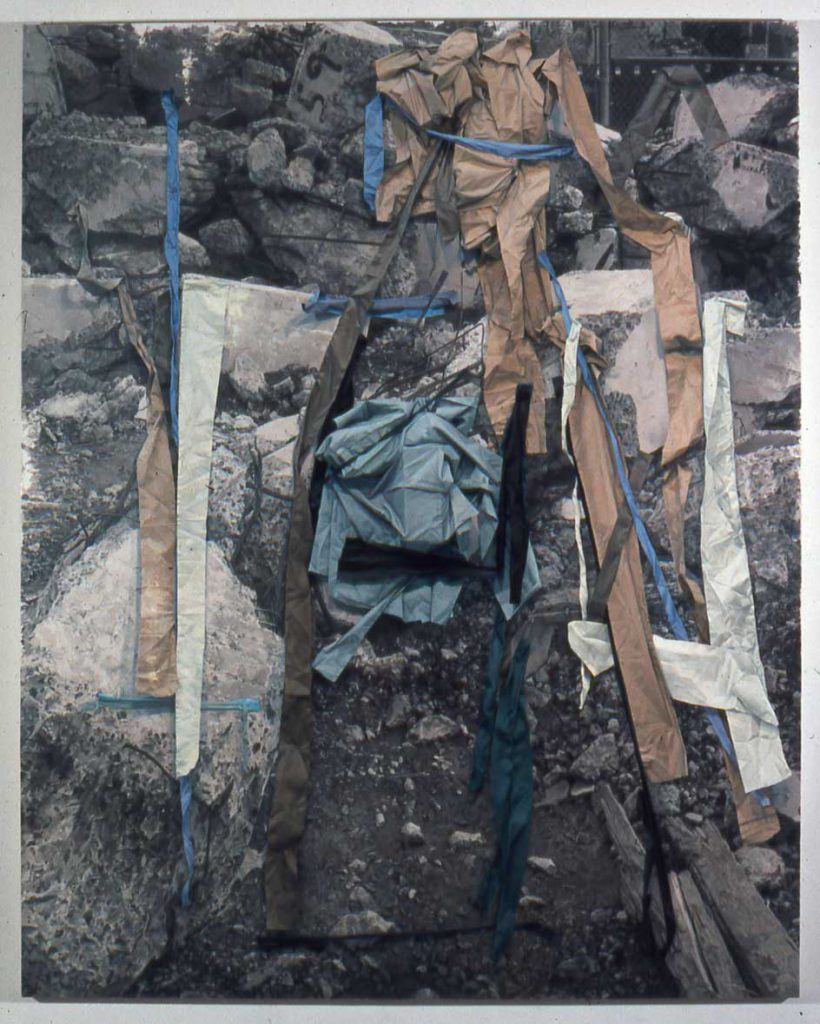

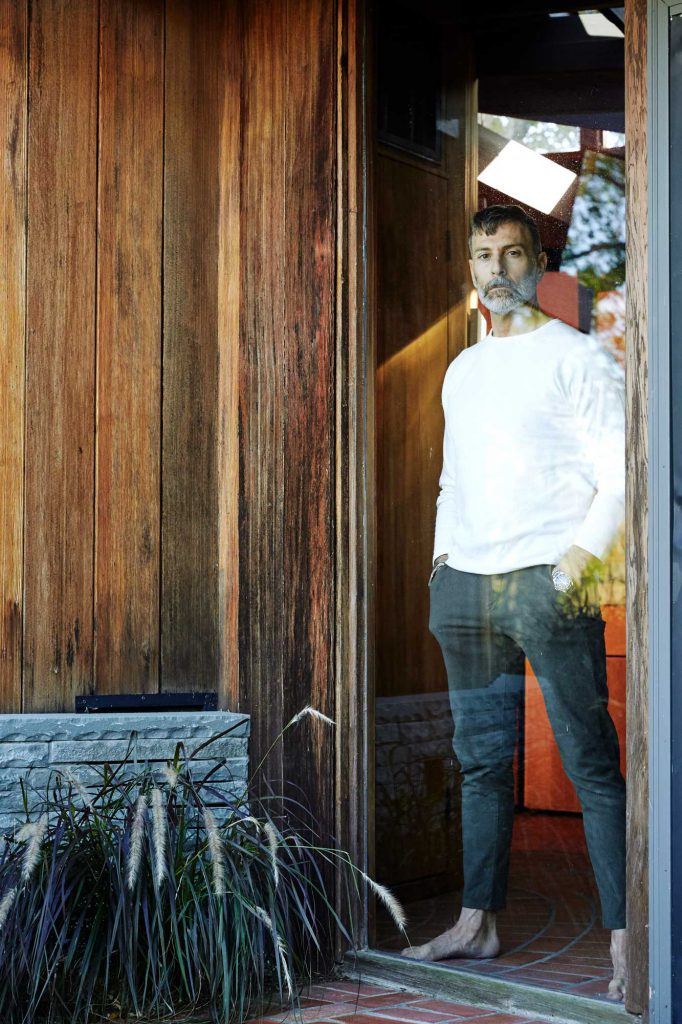

As Light by artist Angelbert Metoyer.

The work in the show takes a deep dive into various historical mythologies…

I have been fascinated with mythologies as long as I can remember, partly because of the mythologies in my own family – that kind of passed-down indigenous pre-American history that is so unique to Louisiana and The South. The title of the show is Golden Horns, which can mean a lot of different things depending on your viewpoint, but the thing that people tend to find first in the work is the Viking Golden Horn thing, but I’m also making references to the walls of Jericho, the golden horn that contains a genie, and the golden-horned deer of Latin mythology, so, yeah, there’s a lot of different aspects in there. Overall, it’s a part of a larger series I have been working on for some years called Magnificent Change, which is always just a place for me to start when I enter into a work. I don’t really know how to explain that or boil it down, but when I work I am always seeking that magnificent change in me with fear and respect, but also confidence and determination. I feel like I’m answering to God with everything I create, you know? And I’m not referring to the on-high God that’s probably in the basement of the Vatican, but the God that has to kind of rise from me. My work is a process that kind of allows me, or my identity, to drop away, and for this abstract formlessness to kind of take stewardship.

Golden Horns exhibits at Tripoli Gallery in Wainscott, New York until August 1

BY JOHN-PAUL PRYOR