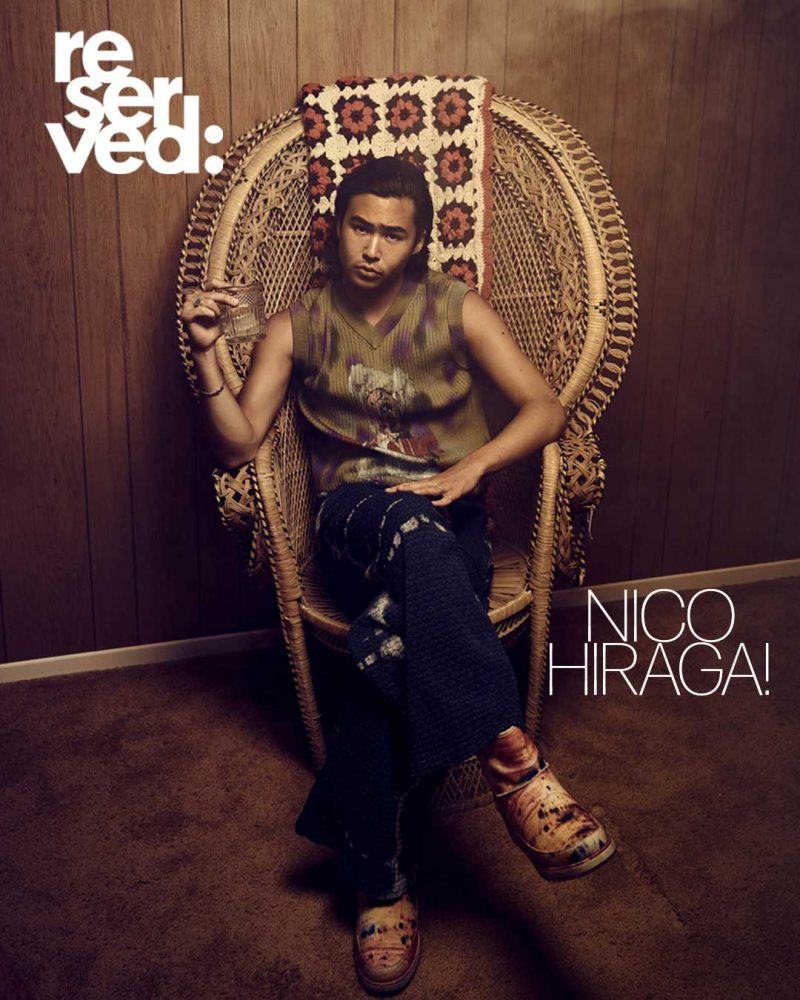

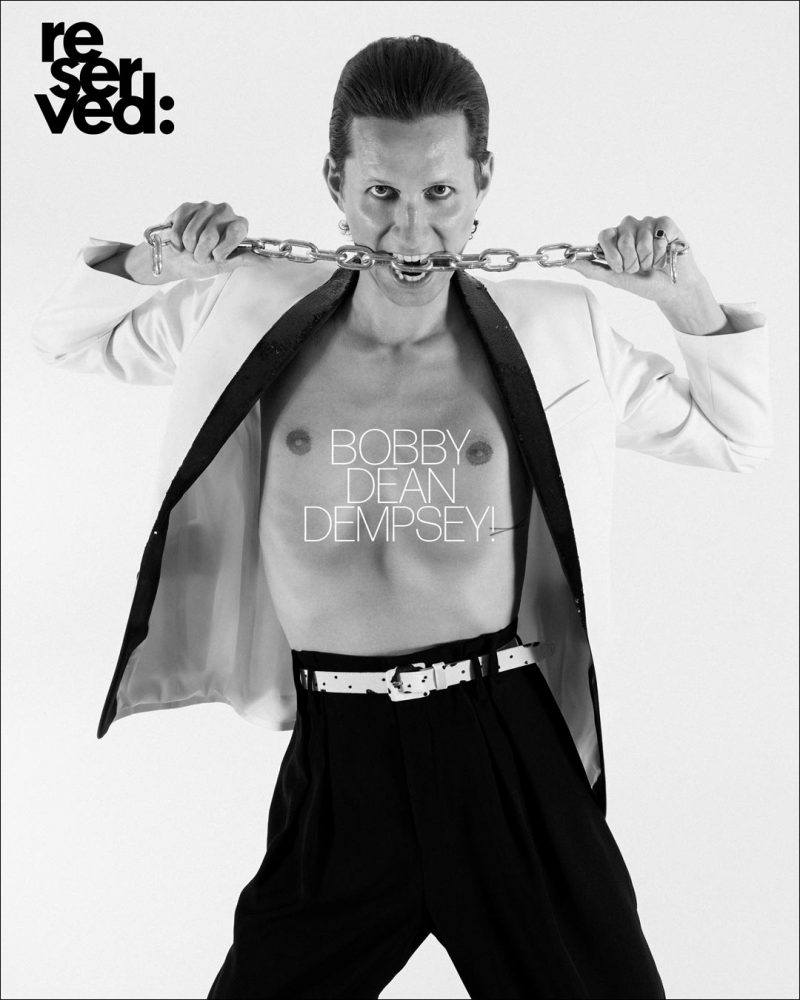

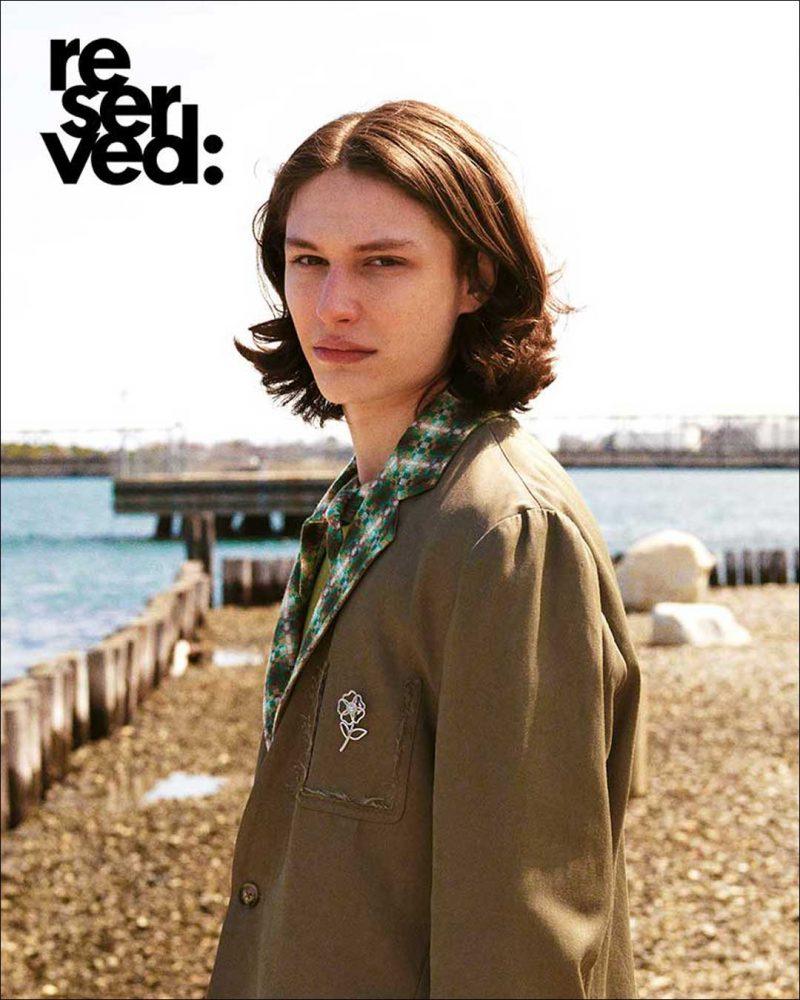

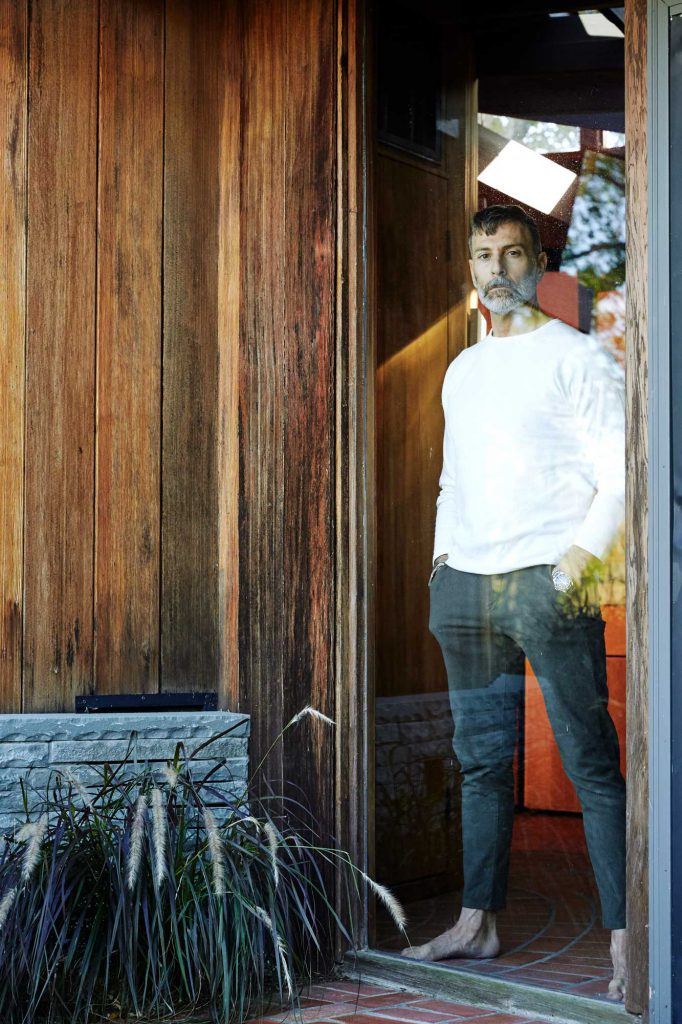

Edzard van der Wyck and Michael Wessley are rebirthing the concept of a heritage brand through Sheep Inc., the trailblazing label under which they create Merino wool pieces, developed to be entirely carbon negative. A background in garment production lent a peek into the ruinous toll this industry takes on our already deteriorating environment, and the pair was inspired to crystallize the opacity of an industry that’s quickly becoming reliant on faster fashion and cutting corners, blind to consequence. The first to inspire such an industry-wide involvement in one’s production process (followed by Stella McCartney and Patagonia, to name a few of many), Sheep Inc. remains humble in their titanic efforts and are only inspired to continue doubling down on positive impact. In their own words and ahead of their latest launch, Sheep Inc. shares their story thus far, exclusively with Reserved.

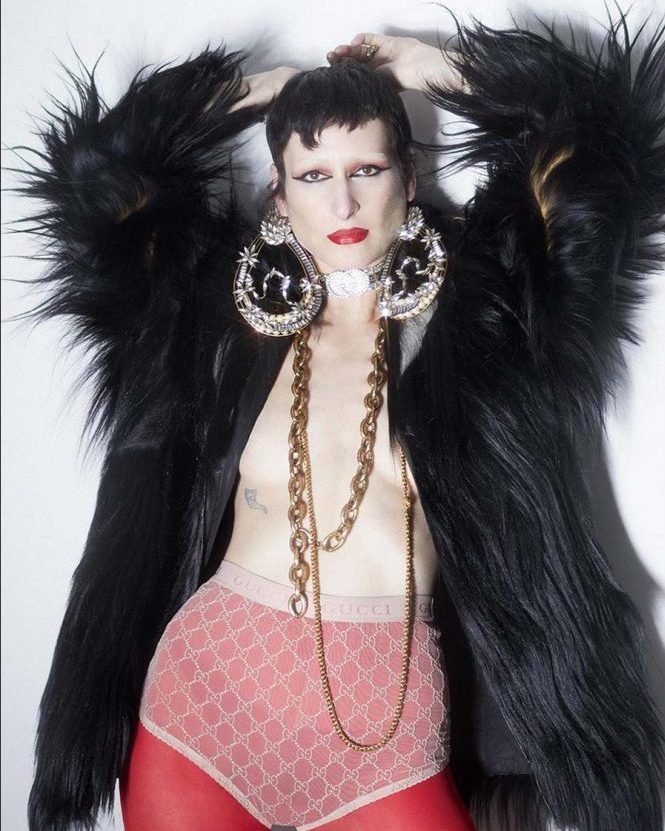

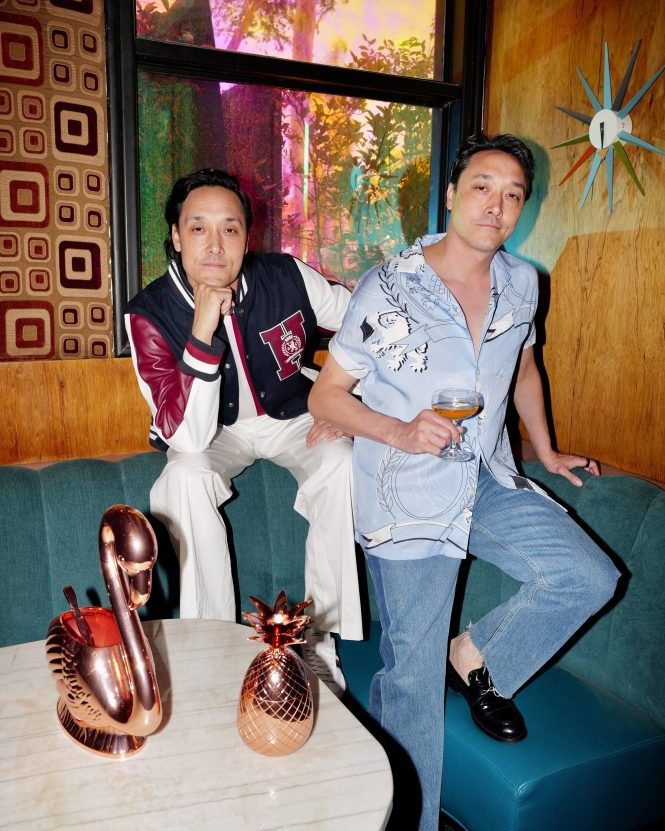

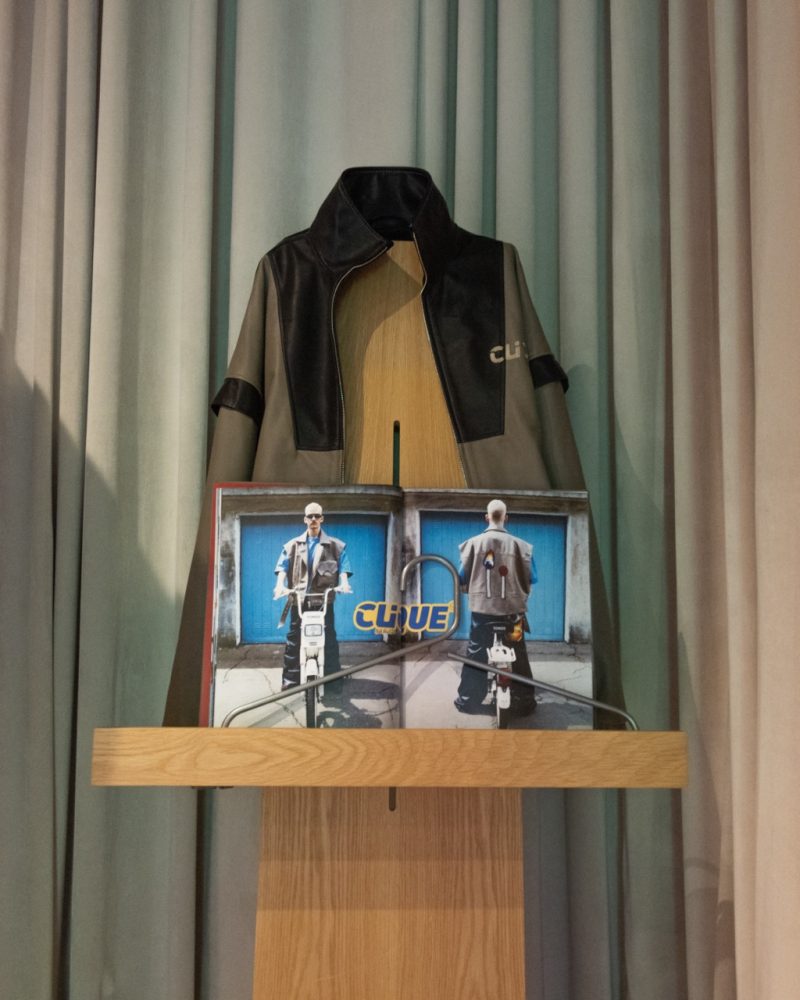

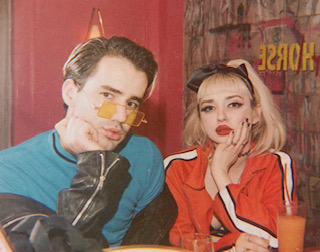

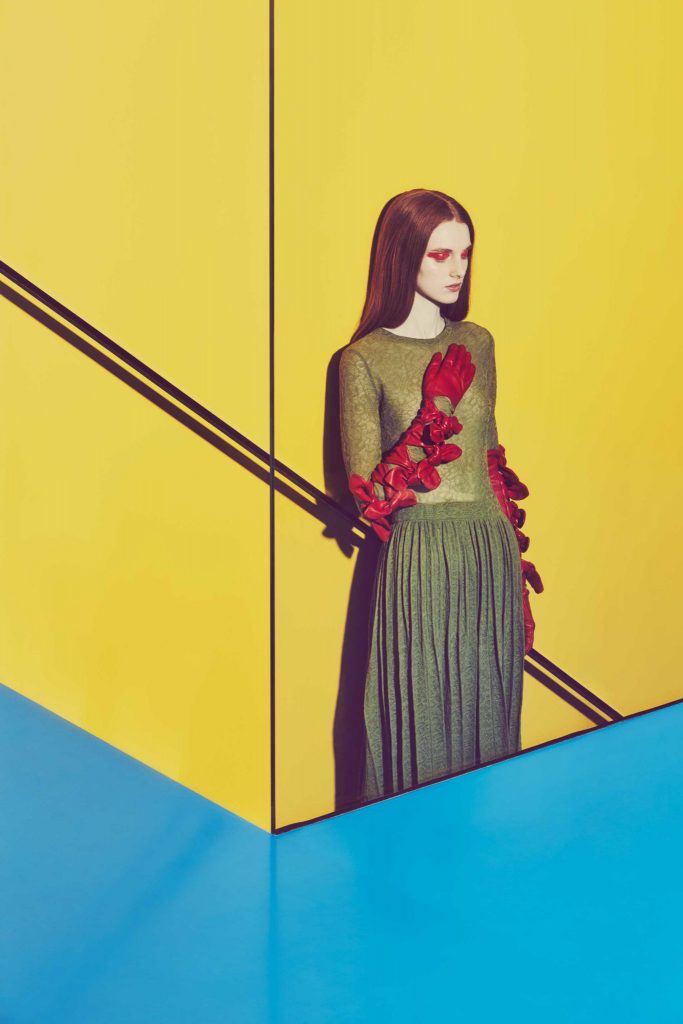

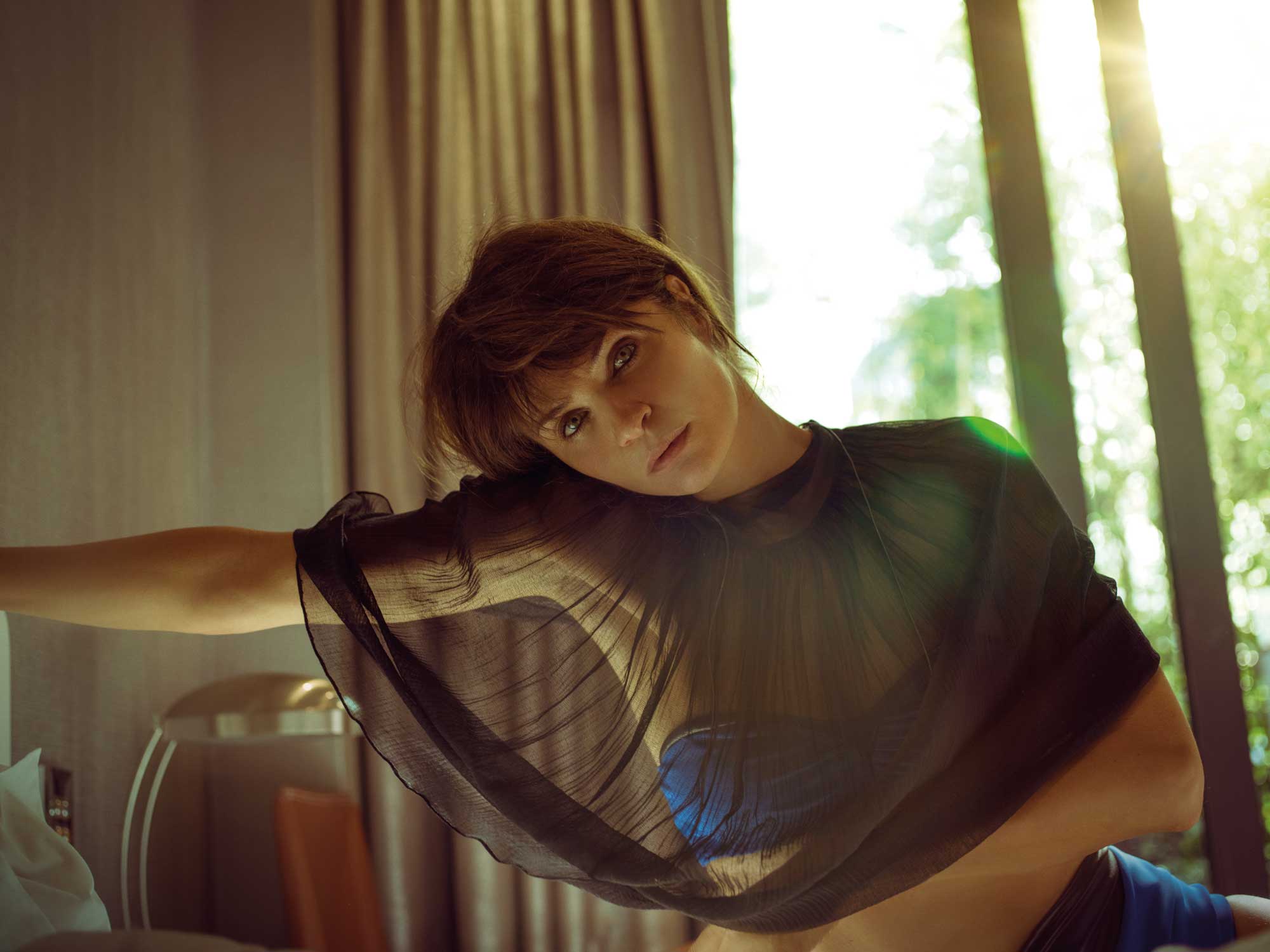

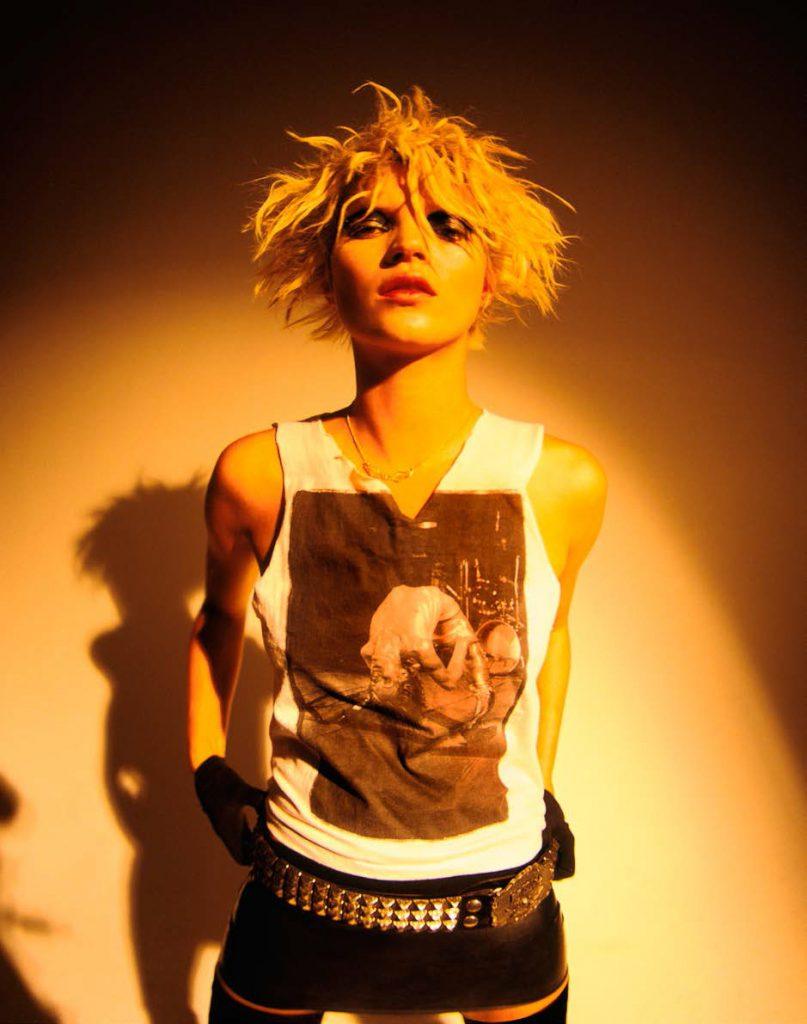

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

Let’s start from the top. Walk me through your story

It probably makes sense to frame how Sheep Inc. came about. I set up a business before this one, also in the clothing space. As I was working in the industry, I started to get real, firsthand insight into the impact of the clothing industry on the environment. I suppose it was quite shocking to really dive into how much damage it was causing. What was even more shocking at the time was that it wasn’t necessarily common knowledge. People didn’t put the clothing industry on the same pedestal as some of the more damaging industries, whether it’s shipping or aviation. Of course, we know that its carbon impact is more than transport. It grew from there. I wanted to figure out how can you create a brand and how can you create a company in the clothing space that very much has an eye on the future and very much understands that there needs to be a different way of doing things? How do you set up a business that looks at tomorrow and says, “These are the decisions we’re going to make to ensure that we have a tomorrow,”? We left my last business to pursue that. I teamed up with my co-founder, Michael, who’s also a great friend of mine. We’d done a venture together in the past and have formed a very symbiotic relationship between the two of us. We did a deep dive into impact in the clothing industry, trying to understand how you could do things differently. What would that look like? What would that feel like? How could you use technology the smart way, to ensure minimal impact? That was the start of a very long journey, in which the end destination was obviously Sheep Inc.

Very early on, we decided we wanted to focus on knitwear. We knew it was an interesting space for us– both passionate knitwear wearers. It sits in every single person’s wardrobe. Knitwear is such a prevalent product. We knew that if we launched a business around it, we could have access to everybody. Everyone could become a customer, because everybody has knitwear. The real impact in the knitwear space comes from the raw material stage and various stages of manufacturing. The other huge issue in the space is that the clothing industry is an incredibly opaque industry. Most brands don’t know where their raw materials are coming from. All of this talk of brands cleaning up their supply chain and cleaning up their act is problematic in the sense that it’s great to put a promise like that forward, but a lot of people actually don’t know where they’re having impact. The first problem to solve is to unpick your own supply chain. We knew first and foremost, we needed to have complete control over the decision-making element every single step of the way. Then, we need to add an additional layer on top of that control, focused on maximizing our impact; Minimizing the environmental impact, but maximizing our positive impact.

Focusing on the raw material stage was our first problem to solve. We quickly identified merino wool as a hugely interesting material. It’s natural fiber, it’s 100% biodegradable, so it doesn’t contribute to the huge textile waste issue that we currently have on the planet. You could put it in the ground, and it disappears in six to twelve months. The problem with it, of course, is that it comes from sheep, and sheep are methane-producing animals. Livestock is a massive contributor to the climate crisis. But, the material made sense in a lot of ways: sustainably, and from a quality point of view. You can turn it into incredibly luxurious and well-wearing garments. Can we justify the use of Merino wool, knowing the CO2 impact that traditional merino wool farms have on the environment? We worked with particular farms in New Zealand who were driving the regenerative farming movement. At the time, this concept was still in its infancy. That was the beginning of a long marriage, working out the carbon impact in the farming stage. The end result of that, by working with these farms that were focused on biodiversity, we were able to source raw material that had a carbon negative impact. There is more CO2 sequestered at source than gets produced by the sheep and the activities on the farm. From there, it became a connect the dots exercise to complete the supply chain. Through that process, we were able to create a product that had a naturally carbon-negative impact. We added every single potential piece of impact into the equation– transport, packaging, end-of-life– into the sum together to ensure we weren’t fiddling the numbers. We want the end result to have an entirely positive environmental impact. We launched with a single crewneck, but we also built a piece of technology to go alongside the garment that allowed us to track garments going through the supply chain, so you could give it a unique digital footprint. This allowed us to be 100% traceable.

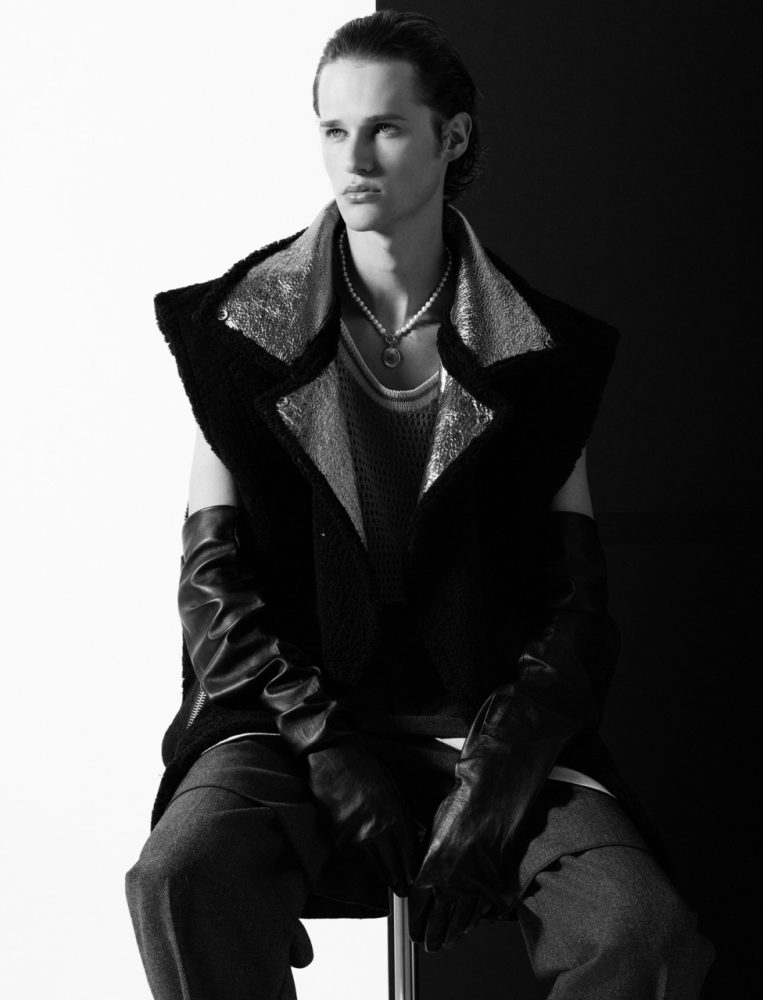

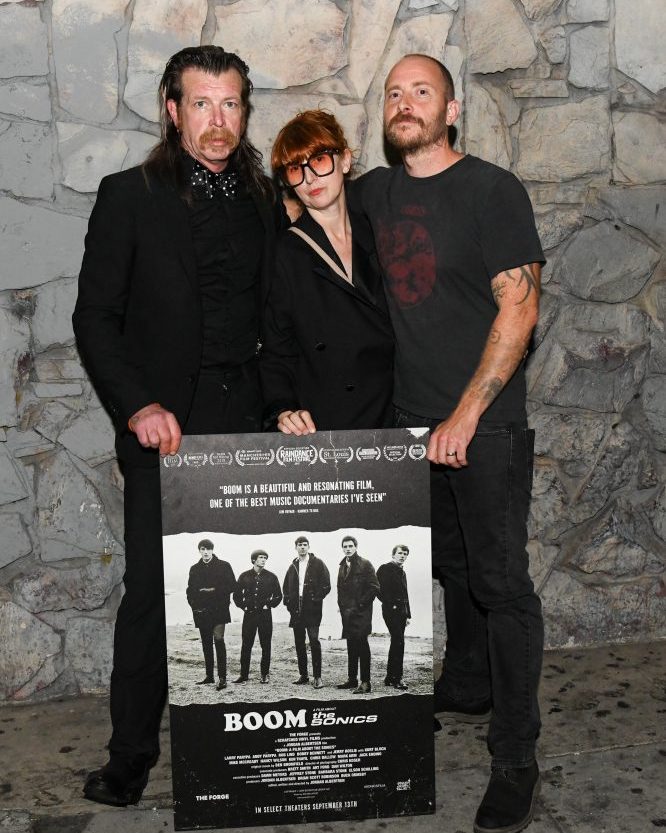

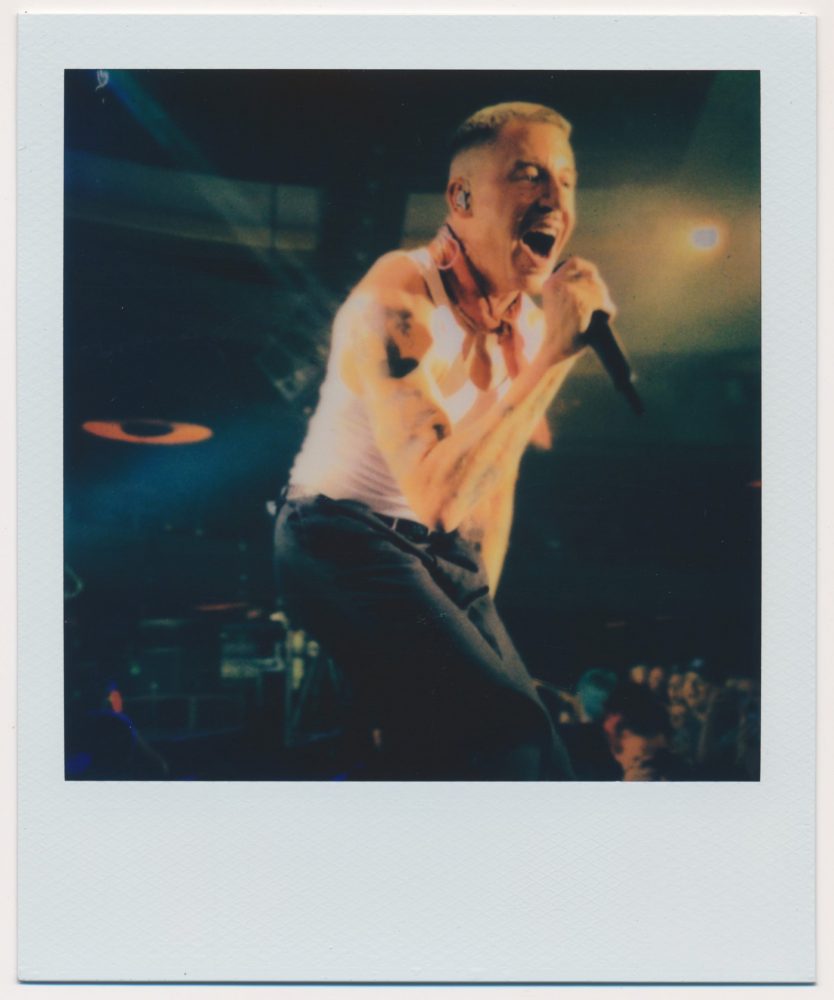

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

A big part of the sustainability culture that we are trying to integrate within culture today does not shed light on the corner-cutting, typically influenced by cost-cutting, involved in their own production processes. Seeing as your own production is such an involved, tailored, and individually managed process, what is the financial impact of this process? How have you been able to balance the cost of sustainability?

We’ve been able to optimize over time. What is important to say is that the price of the garment is reflective of quality, not the sustainability. The price of the wool is set at the price of the quality. For us, there is a premium to the quality, and there is an internal premium to the fact that we have to be very specific about the farms that we work with. From a pricing point of view, we are a premium proposition in the market. I’d argue that we’re cheaper in comparison to the higher-end brands out there. You’re not buying a sustainable moniker. Historically, the problem with a lot of brands that adopt these sustainable propositions is the customer’s feeling that there is an element of sacrifice in these offerings. Either, they are of lesser quality, or something has to give. For us, we didn’t want to do that. We wanted to also make a best-in-class garment, while also making a best-in-class sustainable garment. You can only win in this space if you focus myopically on quality.

Pricing is obviously a very sensitive thing in the market, as we’re not as accessible as some of these more entry-price brands out there. The emergence of fast fashion has made garments a hell of a lot cheaper. There’s this thing of value in the garment– wearability, durability, how long you have it. If you look at what we try to create, we do want something that lasts for generations. I inherited loads of sweaters off my dad and I can still wear them. They’re beautifully made, they come from heritage brands. The quality is just there. This sounds too flippant, but how you make it at that point is less important than the fact that it’s lasted so long. It’s inherently more sustainable, because it has lasted for generations. That idea of fast fashion, which is cheaper, is not going to last as long because you have to replace it.

The heritage craft, pioneering practice approach is what we want to accomplish. Regenerative farming is similar. There are innovative aspects to it, but there’s also just old-school techniques: managing land, rotational grazing so the soil can recover. That’s how they used to do it, before we moved into an industrial farming landscape where everything was so much more damaging. That’s not to say that you don’t add elements like solar powered tractors and ensuring clean water systems. But it is that combination of looking backwards and forward at the same time.

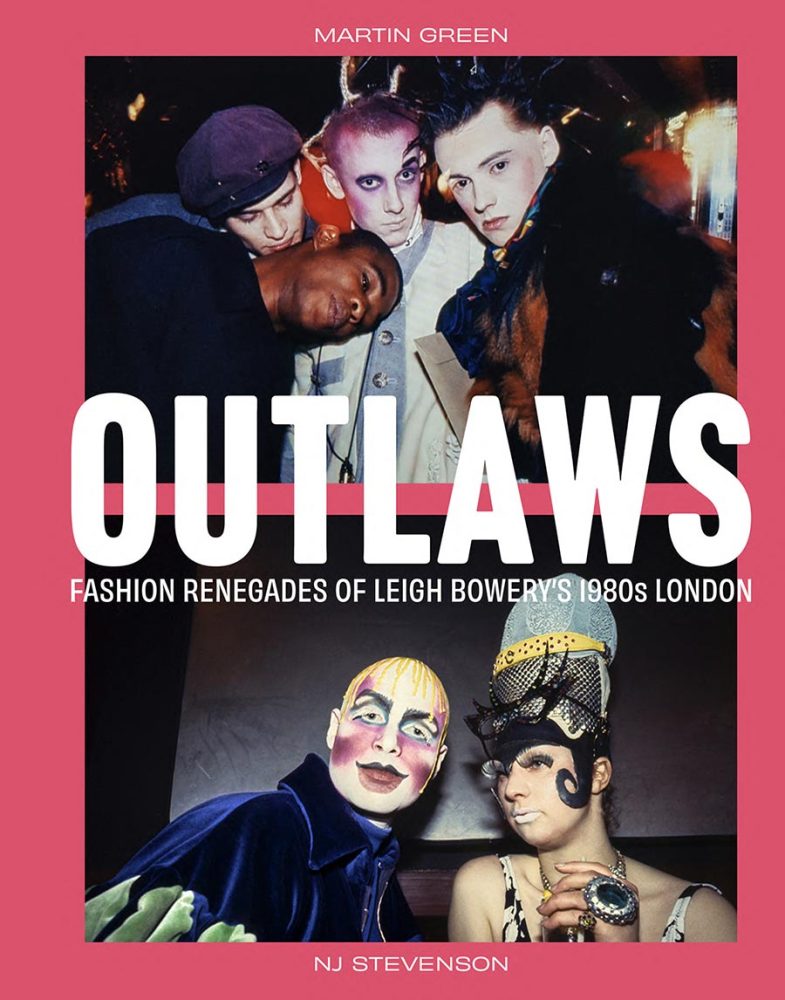

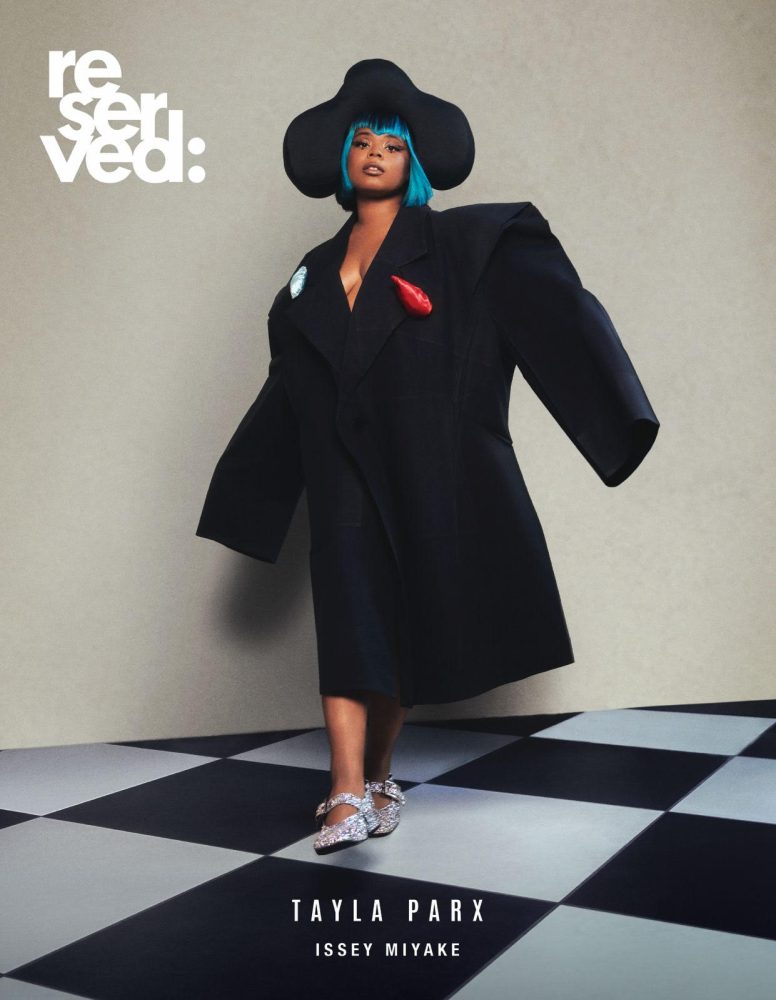

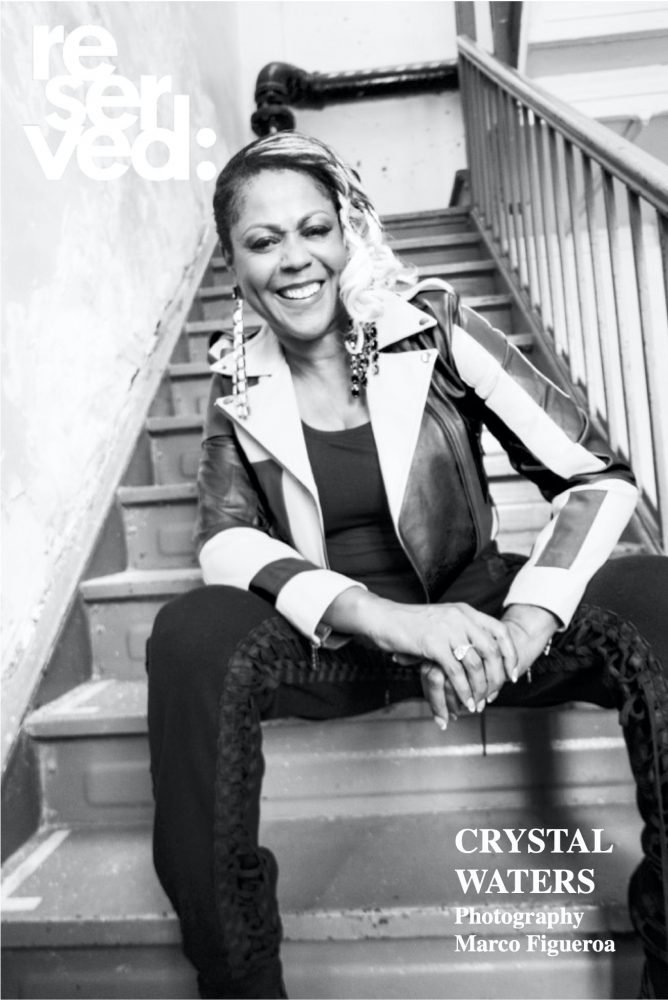

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

- Courtesy Sheep Inc.

Combining that nostalgia and heritage with the high-technology processes that Sheep Inc. has pioneered, what is next for the brand? Are there plans for expansion and exploration?

The slightly-hacky way of saying it is to say it’s always a journey, never a destination. For us, that is very much our mindset. We’re always looking at innovation and we’re always understanding that our impact is still too much. How do we improve? How do we continue to move forward, knowing that we need to practically while staying ahead of the curve? We invest a percentage of our revenue back into the farms, so they can improve their biodiversity projects. It’s this constant movement of elevating the business.

There’s something called the Higg Index coming out in Europe. It’s trying to create a very black and white view of what is good and what is bad in the market. Wool is vilified in the report, because wool can be very impactful. Synthetics, crazily, are said to be less impactful, because there is less CO2 impact due to the sheep element. Nuances are really important when it comes to these things. How you source can make the difference between having wool from a farm where the animal welfare is terrible— that is ‘bad’ wool– and then there is a ‘good’ wool way of doing things. You can’t equate the two. That has to be a more acute understanding. That’s the complex thing about this topic. There is an element of consumer education that has to come in. The consumer has to seek this information. Fashion is historically an opaque industry. People aren’t conditioned to expect an answer from a brand. It’s important to say that wool is one of the best materials to use, if it’s sourced and produced correctly. There is so much it does from a wearability point of view and a positive impact point of view. We’re trying to lace in a bit of education with it.

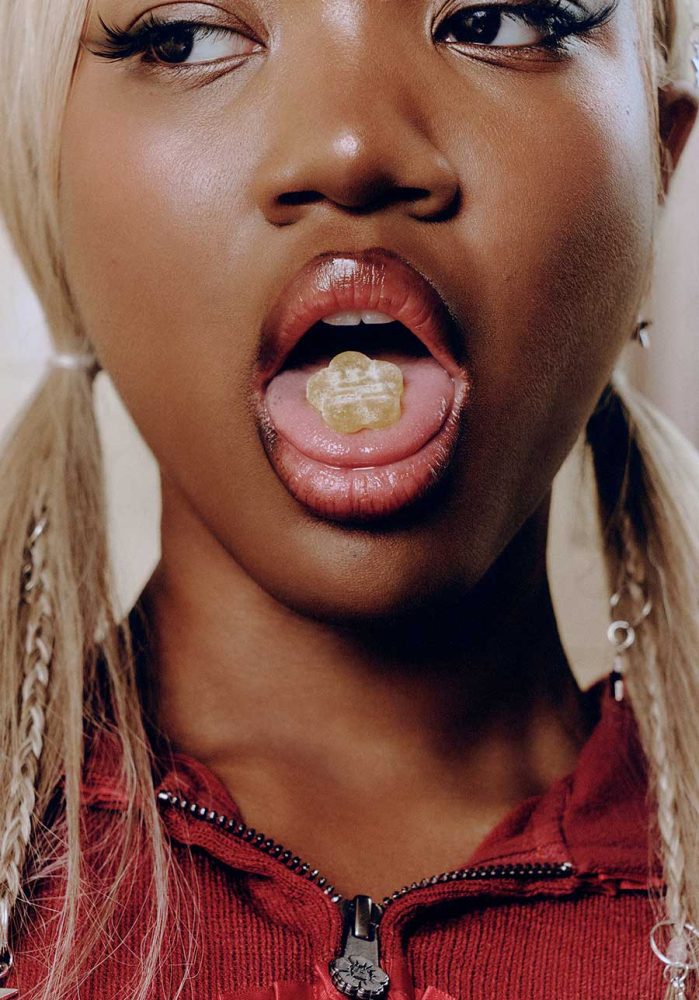

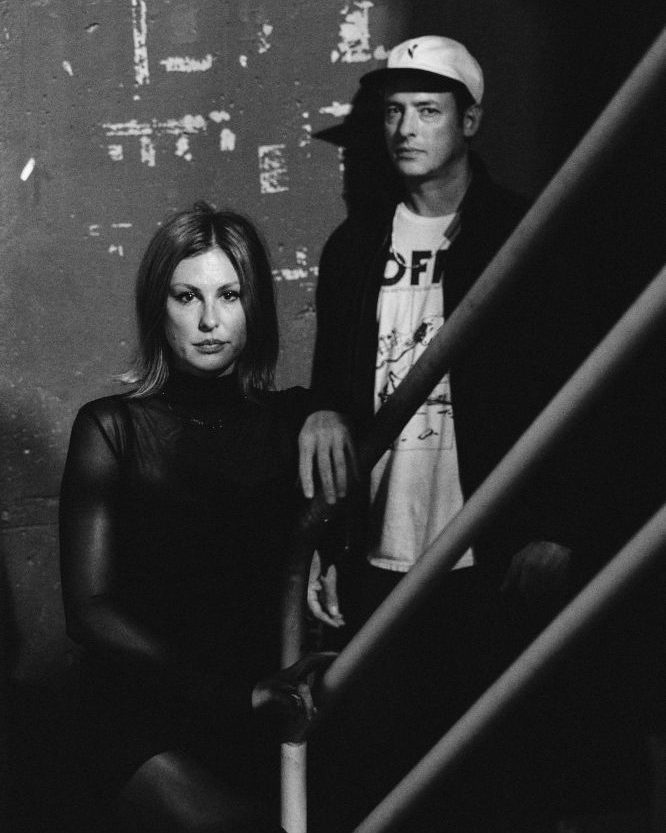

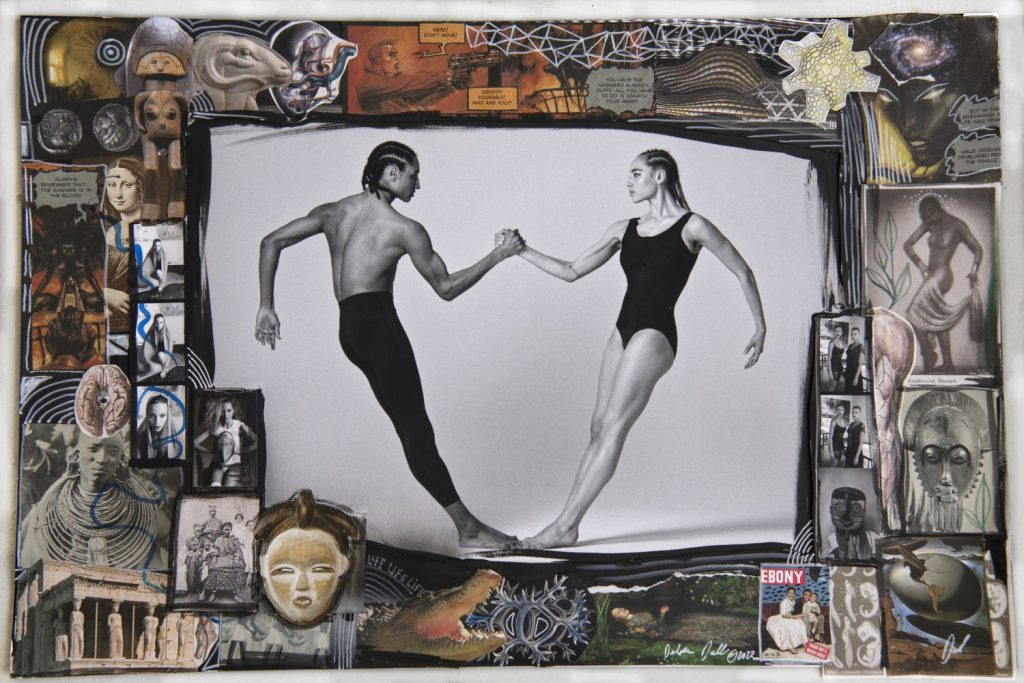

Courtesy Sheep Inc.

Would you fold into that argument, as well, that it’s not entirely about the material itself that makes a textile ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but about the processes that produce these materials?

Brands often don’t know and don’t interrogate themselves. That needs to shift. Transparency has become such a buzzword. Occasionally, there’s this simplistic view of transparency. The important thing transparency is it galvanizes people the have to unpick their supply chains, to understand where to have a better impact, or where they’re being damaging. We really have a strong blueprint for change. Seeing people adopting the same practices is very encouraging.

New collection online now, available for preorder at Sheep Inc.

Courtesy Sheep Inc.